Joseph Graves, an American director, actor and writer, has spent nearly 15 years in China – a country where theater education is almost nonexistent – introducing Chinese youngsters to the rewards and challenges of performance art

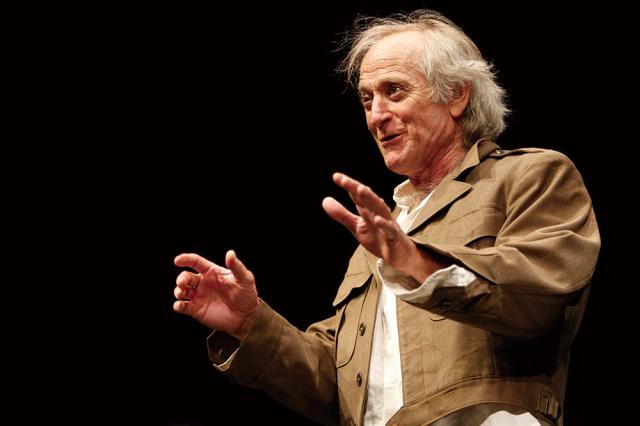

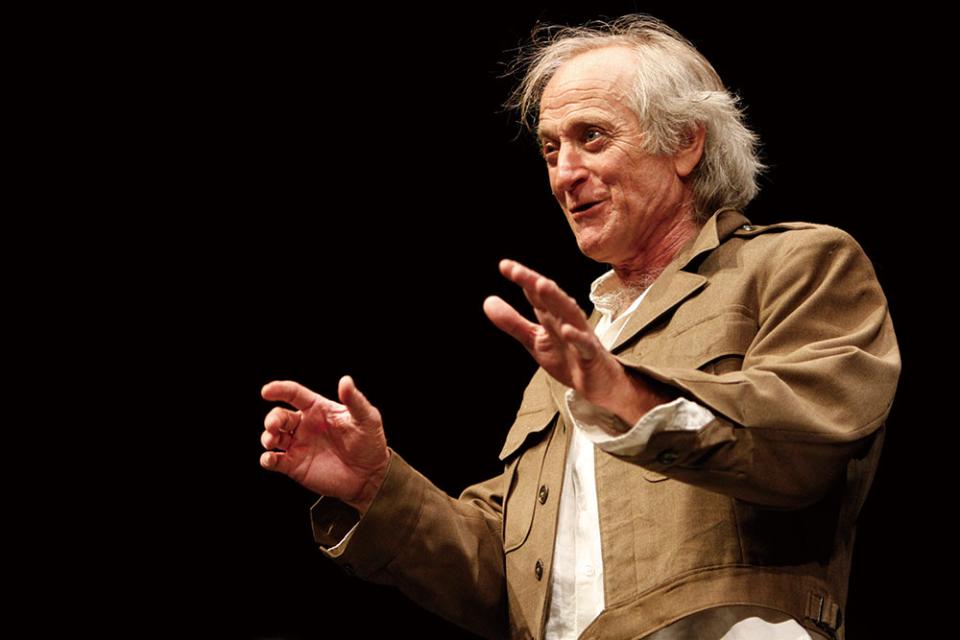

Joseph Graves / Photo courtesy of the interviewee

Rehearsals were at 6 PM. After finishing a quick dinner at a nearby McDonalds, Joseph Graves returned to the basement of the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) Theater. His company was ready on stage – a mix of professional actors as well as 14 children, the youngest of whom was five years old. Graves sat in the stalls and watched attentively, a thick script and a pack of local Chunghwa cigarettes at his side. On July 22, his latest production, a Chinese adaptation of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Broadway smash-hit The Sound of Music, would make its debut in Beijing.

Chinese students and co-workers call him “Joe” or “lao jiu,” “Old Uncle” in Mandarin. Since his teens, Graves has spent his life acting, directing and writing for the theater and the screen, chiefly in the US and Britain, but also in France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand and the Middle East. He is also an expert on Shakespeare, and has directed or acted in all of Shakespeare’s plays.

Since coming to China in 2002, the 61-year-old Graves has produced and directed more than 70 plays in both English and Chinese, including some by Shakespeare and other giants of the Western stage canon, plus musicals and East Asian dramas and operas.

Working as the artistic director of Peking University’s Institute of World Theater and Film, and having visited and conducted workshops at more than 400 universities across China, Graves has become a leading figure in the emerging field of theater education in China. In a country where performing arts education is nonexistent in the vast majority of schools, with the exception of a few arts academies, Graves, a British-born American, has devoted himself to flipping the script.

One Man, Many Parts

“I’ve been doing theater for my whole life. I wrote my first play when I was five, and dragged the neighborhood kids to perform with me. My mom said I was a very strange child. Maybe I still am,” said Graves.

“A large portion of my theater life has been spent working on Shakespeare’s plays. If people ever make me stop writing, directing and performing plays, I really would feel that I am the most worthless human being in the world, since I cannot do anything else. Anybody who thinks about sticking for life [with Shakespeare] will make himself into a ‘worthless’ human being,” Graves joked.

Yet, this lifelong follower of the Bard had what he describes as a “bizarre, almost violent” initial encounter with his future idol. Born and raised for much of his early life in England, Graves was introduced to Shakespeare in the 1960s at the age of six by a person who changed his life – the alcoholic principal of his London boys’ school, Clive T. Revel. Revel, as Graves described, was what George Bernard Shaw had referred to as a “Bardolater” – someone whose passion for Shakespeare borders on the maniacal. Revel taught Shakespeare in an eccentric and “blitzkrieg” fashion that terrified his students.

In his 50s, Graves would draw on his experiences at school to pen his autobiographical one-man play, Revel’s World of Shakespeare, a witty and moving account of childhood confusion and exploration of both Shakespeare’s works and an odd mentor/student relationship spanning 40 years. The show has been performed more than 200 times all across China, and has been well received by local audiences.

In 2002, Graves was invited to China by Professor Cheng Zhaoxiang, former head of the English department at Peking University and one of China’s leading Shakespeare scholars, to coach his students on performing Shakespeare.

“Professor Cheng found me, and told me that [although] he had taught Shakespeare for over 25 years, he felt he had never done it right, because he knew nothing about acting and directing,” said Graves.

Graves had no prior experience with teaching college students and, viewing the opportunity as a challenge, agreed to give it a shot.The first play he chose to teach in China was The Tempest. He posted an audition notice on the school’s website, and the Chinese students’ enthusiasm – over 4,000 students came to audition for a play with only 20 speaking parts – astonished him.

“That was kind of shocking to me, because if I am about to do a play in an American school, perhaps 20 people would be interested,” he joked. Graves ended up watching 800 of them audition over the course of a week before choosing 80 of the most gifted and passionate performers for four separate casts.

To Graves, the experience was a “lifechanging” theatrical experiment. “None of these students had ever been in a play. Most of them had never seen a play. They were so passionate and intelligent – many of them were very talented but didn’t realize it. They needed help and guidance,” he said.

In 2004, Cheng and Graves founded the Institute of World Theater and Film, with Graves as artistic director.

Each semester, the institute produces a full-length, English-language theatrical production. In its 12 years of operations, it has produced 12 Shakespeare plays, and dozens of other notable works including Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, Molière’s The Hypochondriac, Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, Arthur Miller’s All My Sons and Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie.

These English-language stage productions, featuring more than 3,000 university students, have been seen by tens of thousands of people all across China, with some productions touring the US, Britain, New Zealand and the Middle East.

Graves also encourages his students to create their own plays. His former student Hu Xiaoqing, now a successful theater director and playwright, has written adaptations of The Monkey King and The Magic Lotus Lantern that premiered in Beijing before touring the US.

Strutting, Fretting

“I always see [Graves] as a Dr [Norman] Bethune kind of figure in Chinese theater,” said Li Shi, an experienced producer and actor with Peking University’s Institute of World Theater and Film, comparing Graves to the Canadian physician who served with Mao Zedong’s Eighth Route Army in the late 1930s and was posthumously recognized as a hero of the Revolution.

“There is always a person in your life that opens up a brand new world to you. To me, Joe is that person,” Li said. Li was formerly a website engineer and photographer, knowing little about theater and Shakespeare until he attended one of Graves’ two-week-long theater workshops in 2006. He was instantly hooked. Li has been involved in productions of The Tempest, Così, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Julius Caesar, Einstein’s Dreams, My Fair Lady and The Monkey King.

“It is Joe’s dedication and enthusiasm that drew me into this profession. What Joe wants to do is so meaningful and I think he needs more help. So I decided to follow him,” Li told our reporter. “Another thing that impresses me deeply is his vitality as an actor. He is over 50, yet still extremely strong, energetic and full of life and strength on stage. I am so amazed.”

“His instruction opens everyone up,” said Chen Hui, a former law student from Beijing International Studies University. “He believes anyone can be a good actor or a good playwright as long as one makes the effort. He always tries his best to guide everyone to find his or her undiscovered talent.”

Working with Graves on productions of Servant of Two Masters, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Tempest has made Chen determined to pursue a career in theater. This year, she will enroll at Drama Studio London for further professional training.

Doing plays with inexperienced student actors involves a lot of demonstration and explanation, especially when dealing with the early modern English and iambic pentameter of Shakespeare.

“It’s unfair to compare [my students] with professional actors,” said Graves. “The Chinese student actors that I’ve worked with have to study Shakespeare’s language so hard because it’s so difficult for them. English is the students’ second language, while Shakespeare’s language is like a third.”

Graves believes that Chinese student actors, who painstakingly study Shakespeare’s use of language, examining each vowel and consonant, are sometimes superior to their Western peers at recognizing the subtlety and peculiarity of the language and gaining more insight into how Shakespeare “uses the sound to create emotions, ideas and feelings.”

“Their skills as actors are limited but their intelligence, their passion and their capacity to connect with the words is equal to a really wonderful Shakespearean.”

Such subtlety, as Graves told NewsChina, is often ignored by professionals in the West. “They are too familiar with the language. Sometimes they might forget how powerful just the language itself can be.”

As his students and coworkers describe, when it comes to Shakespeare’s language, Graves can be very strict.

“He always underscores the music of the English language. Each vowel sound should be fully articulated, and each consonant clear. The extent to which Joe is strict and precise with delivery and language is no less than that of any great musician with notes,” said Chen Miaojuan, former president of Peking University’s English Drama Society.

Graves’ professional-level demands regarding delivery and language also made a deep impression on Wang Yuyu, an English major at Tsinghua University who worked with Graves on productions of Così, Servant to Two Masters and The Tempest. Wang told our reporter how strict Graves was when he was helping her prepare a monolog by Joan of Arc in Henry VI, a passage she used as her audition piece for drama schools.

“He corrected each vowel and consonant that I failed to articulate well, word by word, line by line. The slightest error would be pointed out and I was asked to do it again and again. Practice of this one-minute monolog lasted over two hours. I felt frustrated, and he seemed to feel frustrated as well, smoking cigarette after cigarette,” she recalled. The effort, it seems, paid off. “Such strict instruc tion did help me a lot. Interviewers from American drama schools were amazed and wondered why a Chinese student could grasp Shakespeare’s words so well,” Wang told NewsChina. This fall, she will begin studying performing arts at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in London.

Graves’ PKU institute collaborates on a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with a New Zealand theater company / Photo courtesy of the interviewee

The Play’s the Thing

Graves’ institute’s latest production, part of a June tribute to the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, was The Tempest. The theme of this year’s Beijing Fringe Festival will be a salute to Shakespeare, recognized in China as in the West as the world’s greatest dramatist. All 37 of his plays will be performed by different Chinese theater companies. Graves’ production of The Tempest will be the festival’s only production performed in its original language.

Graves is also engaged in promoting musical theater in China, helping his institute produce musicals such as Fiddler on the Roof, 1776, and The Three-Penny Opera.

Since 2012, Graves has cooperated with Beijing-based theater company Seven Ages, founded by his former student Yang Jiamin, which is trying to simultaneously introduce Western musicals to China and also devise Chinese adaptations. Graves has already directed local productions of Man of La Mancha, Avenue Q, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying as well as the upcoming The Sound of Music.

Having performed across China, Graves observed that audiences in so-called firsttier cities are very different from those in the provinces. Young people living in Beijing or in Shanghai are generally more exposed to theater, whereas in smaller cities, “most people don’t know what a play is.”

“One of my favorite places to perform is in comparatively small cities where they don’t get a lot of theater. The response is the way I responded to plays when I was a child. They are carefully listening to the story, interested in the spectacle.”

A “gigantic difference” between Chinese and Western audiences that Graves says he has observed is their average age. “If you perform a play in New York or in London, 90 percent of audience members are 45 or older, while in China, 90 percent are 40 or younger,” he said. “Take my one-man show, I would say 95 percent of the audience members that attended the show were 30 years old or younger,” said Graves.

“Theater is very expensive in America. Many young people cannot afford to go to the theater; they will go to a movie. Theater in China is not that expensive. Young people in China go to the movies and also to the theater,” he added.

Young Chinese, he explained, are “very much open” to Western plays, approaching them with passion and “inquiring minds,” qualities he has found lacking in many of their counterparts in the West.

After conducting workshops at more than 400 universities and influencing thousands of young drama enthusiasts, Graves admitted that the number of students he can reach is still limited.

As he pointed out, theater education in China lags far behind the West in terms of teaching, funding and policy support. “No general university [in China] has a performing arts department. Some universities have an art department, but all are theoretical. There are a few arts schools in China but they only reach the tiniest fraction of the people.”

“Among the comparatively small numbers of children I am able to reach, all of them are interested in drama. But there is no funding to support them and no people to teach them. So all you have is students [who] form clubs for themselves.”

“The idea behind theater education,” he continued, “is not so much to train people to be professionals, but to expose students to creative thinking and creative ideas, and art is the best way to do that.”

Theater education, as Graves emphasizes, not only offers rich life experience, but also helps foster a creative approach to choosing a career. He also believes that education can help create a “need” for theater.

“Art nourishes our souls,” he said. “If theater education happens, people will see and understand what the theater is and understand it as enjoyable and even valuable to our existence as human beings. They may become patrons of the arts.”

Old Version

Old Version