When the Cultural Revolution began, Xu no longer had permission to publish his translations. In private, he translated Mao Zedong’s poems into English and French.

Xu was particularly proud of a line from his translation of Mao’s 1961 poem “Militia Women: Inscription on a Photograph,” which eulogizes the brave female soldiers who “love their battle dress, not rouge and blush.” Xu translated the line as “They love to face the powder and not to powder the face.”

The Red Guards accused him of “twisting Mao Zedong’s thoughts and avoiding class struggle” and punished him with a public flogging. Xu was forced to sit under a tree and was lashed 100 times with a branch. He returned home that night, slashed and bruised. Unable to use a chair, he sat on an inflated swim ring that his wife prepared for him and jotted down another translation of a Mao poem that popped in his head during the ordeal.

Xu sent his translations of Mao’s poems to his teacher and author Qian Zhongshu, one of the most prominent liberal arts scholars of 20th century China.

On March 39, 1976, Xu received Qian’s reply: “You’re dancing while chained by rhyme and rhythm, but the dance shows amazing freedom and beauty, which is quite extraordinary.”

“[Free translation] may damage the overall translation, while [literal translation] may harm its prose. Balancing the two is always an issue. Like British scholar and critic Richard Bentley’s famous remark on Alexander Pope’s translation of The Iliad: ‘A pretty poem, but you must not call it Homer,’” Qian wrote.

In 1995, Xu’s translation of French author Stendhal’s 1830 novel The Red and the Black stirred debate among translators.

A major participant in the debate, Xu Jun, a tenured professor of liberal arts at Zhejiang University and standing vice president of the Translators Association of China, recalled this “battle of opinions” to NewsChina.

Translations of Western classics in China surged after the country joined the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literacy and Artistic Works in 1992.

The Red and the Black had nearly 10 translations. Xu sent his translated version to Xu Jun, who was then dean of the Department of Western Language and Literature at Nanjing University, Jiangsu Province.

In March 1995, Xu Jun and Xu Yuanchong corresponded with letters declaring their opposing views on what makes a good translation. Both letters were published in the Wenhui Reading Weekly. Soon, translators across China were joining the debate.

At an academic conference in Hong Kong that year, leading translator Feng Yidai listed several charges against Xu Yuanchong’s version of the novel. He criticized Xu as being “a sinner through the ages” for “overusing four-word Chinese idioms,” “advocating unfaithful translation” and “shamelessly boasting about his wrong translations.”

Xu stood his ground. At the conference, Xu argued that literary translation is a contest between two cultures, and four-word idioms are an advantage of Chinese literature. A translator should make the most of expressions in the target language.

“Chinese readers, who had long been misled by rigid translation, mistook pidgin Chinese and translationese as the right translation,” Xu argued.

“To translate faithfully is just the starting point, while to translate beautifully is the higher standard,” he added.

Xu Jun told our reporter that during a private meeting with Xu Yuanchong in 1998, he argued that “a translation that strays too far from the original is a disloyal beauty.”

“The nature of translation is a kind of communication, so fidelity is the most essential criterion,” Xu Jun told our reporter.

Xu Yuanchong said that the real enemy is overly literal translation. “Literature is pointless if its beauty has been deprived,” he said.

Xu Jun belonged to the “surgical” school of translation, he said, focusing more on form, while he belonged to the “holistic” school, which focuses more on essence of meaning.

“[Xu Yuanchong] said: ‘I’m 33 years older than you... but your ideas are old. What you advocate represents an old time, an old world. Though I’m older than you in age, my ideas are brand new. I stand for a new world,’” Xu Jun told NewsChina.

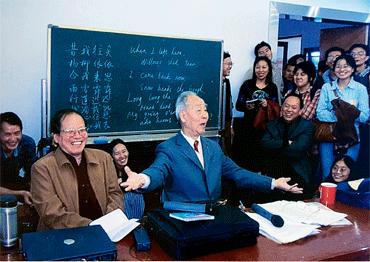

Since 1983, Xu Yuanchong has been a professor in the English department at Peking University. As if making up for lost time, he dedicates every available moment to translation.

For Wang Qiang, co-founder of the New Oriental Group, China’s leading private education company, Xu is his most respected teacher. His long friendship with Xu developed while a student at PKU in the 1980s, when he and another classmate Liu Feng often visited Xu’s home. Wang said he still keeps in touch.

Wang most admires his teacher’s consistent dedication to translation. “Every day right after he gets up, Professor Xu sits at his desk, pondering the diction, rhythm and rhyme of his translations. He has been doing it for decades,” Wang told NewsChina.

Zhao Jun, Xu’s wife of 60 years, died in 2018. Wang Qiang and Liu Feng visited him the following day, worrying how their 97-year-old teacher was holding up.

To their surprise, the elderly translator was sitting at his computer with a copy of The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. He was translating Wilde’s famous play “A Woman of No Importance,” which was ironic considering the loving relationship he had with his wife. Her photos were all over the home.

“Professor Xu told us that after his wife passed, he stayed up all night and sat at his computer for quite a long time. Then he decided to translate Oscar Wilde. He asked us not to worry about him, saying: ‘As long as I’m still able to get lost in the world of translation, I won’t fall apart,’” Wang told our reporter.

Xu translates roughly 1,000 words a day, working until 3 to 4am, sleeping for about three hours, and getting up at 6am to continue.

He recently finished a translation of Henry James’s masterpiece The Portrait of a Lady and plans to publish it in December, 2020.

Though Xu Yuanchong and Xu Jun never yielded to each other’s views, the two have maintained a decades-long friendship. In correspondence, the elderly translator would call his friend “Xu Jun my little bro.”

“We never wavered on our positions over the years. But I think beneath the discrepancies we are actually the same - we both see translation as a spiritual pursuit. Literary translation expands the realm of ideas,” Xu Jun told NewsChina.

Old Version

Old Version