The recent ruling from the Hague arbitration court is not a victory for any party with a stake in the South China Sea

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague ruled overwhelmingly in favor of the Philippines over China in the arbitration case brought by the former over disputes in the South China Sea. After the PCA announced its verdict, the international media focused its attention on China’s refusal to accept it, portraying China as disrespectful of the “rule-based international order,” a concept repeatedly emphasized by US officials in recent months.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague ruled overwhelmingly in favor of the Philippines over China in the arbitration case brought by the former over disputes in the South China Sea. After the PCA announced its verdict, the international media focused its attention on China’s refusal to accept it, portraying China as disrespectful of the “rule-based international order,” a concept repeatedly emphasized by US officials in recent months.

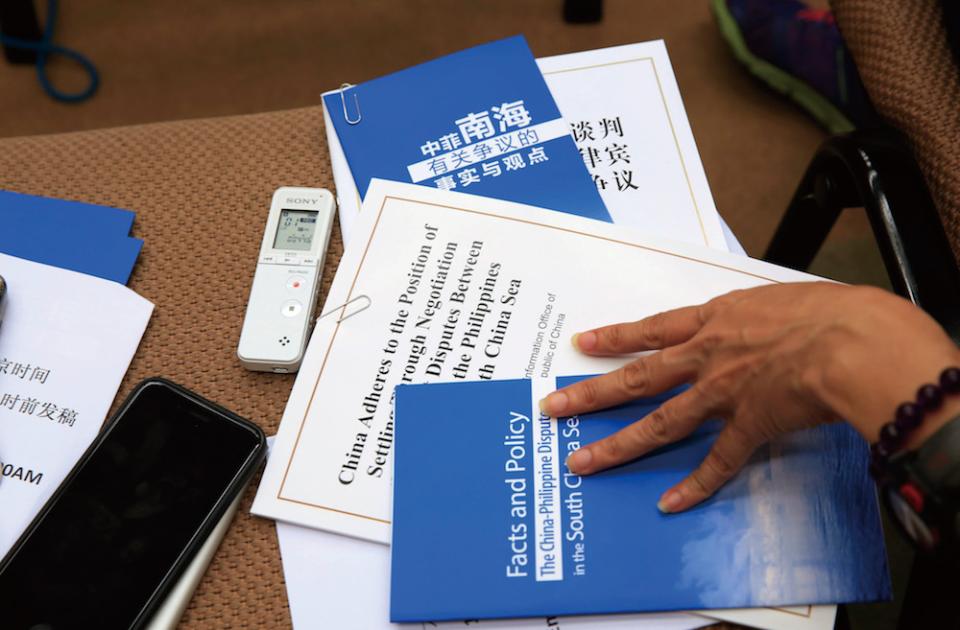

A reporter reviews South China Sea policy papers at a press conference, Beijing, July 13, 2016 PHOTO BY IC

Authority

Throughout the proceedings, China has maintained that UNCLOS’s Article 298 protects its right to not accept compulsory procedures regarding settlements of this kind of dispute, therefore China would not participate in the case.

According to Article 298, a signatory state has the right to declare that it excludes certain disputes from arbitration procedures, including those concerning “sea boundary delimitation, or those involving historic bays or titles.”

China made this Article 298 declaration in 2006. About 30 other countries have made similar declarations, including all of the UN Security Council permanent members, with the exception of the US. The US has not ratified UNCLOS.

However, the PCA argued that since the Philippines explicitly asked the court not to demarcate boundaries, the case is not about sea boundary delimitation, and thus the PCA has jurisdiction over the dispute.

This is ostrich logic. As the tribunal effectively ruled that China’s claims to historical rights to the territory within the “nine-dash line,” its proposed maritime delimitation line, have no legal basis, this case has everything to do with “maritime delimitation” and “historical titles.” By effectively redefining Article 298, the tribunal overstepped its authority on an unprecedented level.

The PCA has also unprecedentedly altered concepts outlined in UNCLOS. The most notable case is that of what constitutes an “island;” UNCLOS’s definition is very vague. Apart from stating that an island must be above water at high tide, the agreement’s Article 121, which addresses the issue with a total of some 80 words, only says that “rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” In other words, geographical features deemed “islands” allow their sovereign states access to surrounding resources found in their exclusive economic zones, while “rocks” do not.

Chinese fishermen have used the South China Sea islands as “traditional fishing grounds” for a long period of time, according to the Chinese government. In concluding that all features involved in the South China Sea dispute cannot sustain human habitation on their own, the tribunal justified its decision based on an argument that this historical presence of Chinese activity did not establish what the panel called “a stable community.”

This goes substantially beyond what is mentioned in UNCLOS. Contrary to making a judgment based on whether a feature has enough natural resources to “sustain human habitation,” as implied in Article 121, the tribunal chose to adopt a completely different criterion: whether or not these features had been home to a historical population and economic activities.

The decision to adopt a certain interpretation arbitrarily, while rejecting alternative interpretations, is inevitably and intrinsically political. There is ample reason for China to feel that the ways in which UNCLOS was interpreted were specifically chosen to nullify China’s position.

The PCA judges should be aware that there is a reason why Article 298 was included in UNCLOS and why Article 121 used broad terms; it was to accommodate the different voices of different countries. That is the very reason many countries agreed to sign the treaty in the first place. When UNCLOS was drafted, it went through a consensus process involving representatives from more than 160 countries. Such a consensual spirit should be respected rather than disregarded.

International law is not about letting a few individuals dictate interpretations and forcing them on member states. It is about seeking consensus on rules, albeit sometimes only vaguely defined ones, so that sovereign states can agree to be constrained.

By changing the precise definition of concepts on a document created with the consultation of thousands of legal experts from around the world, the tribunal, which was composed of just five judges, betrayed the very spirit upon which UNCLOS was established.

Impartiality

Besides the tribunal’s questionable jurisdiction over the matter, another major controversial issue that has largely escaped the attention of Western media is that of the credentials and objectivity of the judges on the PCA panel.

Four of the tribunal’s five judges are from Europe, and the fifth is from Africa. This composition is hardly representative of the international community at large. None of them have solid credentials in Asian affairs nor an educational background in Asian history.

China questions the impartiality of not only the five-judge panel, but also the judge who decided the court would hear the case. In China’s view, the timing of the ling of this case was well calculated. The Philippines led the case in 2013, when the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, a panel established to handle UNCLOS disputes, was presided over by Shunji Yanai, a judge from Japan. Under Yanai’s leadership, the court decided to hear the case, and Yanai personally appointed four of the tribunal’s five judges. The fifth was named by the Philippines.

Yanai is a veteran politician deeply involved in Japan’s foreign policy e orts. He served as Japan’s vice-minister for foreign affairs from 1997-1999, and the ambassador to the US from 1999-2001. In 2007, Yanai served as the chairman of an advisory panel devoted to revising Japan’s constitution to allow military action overseas.

As Japan has been locked in its own disputes with China over territory in the East China Sea and has become increasingly involved in the South China Sea disputes, there is every reason to question the objectivity of Yanai, given his past diplomatic roles.

Some have blamed China for the arrangement, arguing that China could have prevented this if it had not refused to participate in the arbitration. If China had agreed to participate, it would have been able to name one judge and jointly appoint three others with the Philippines.

This argument betrays the very political nature of the case. If the PCA cared about neutrality and fairness, it should have taken e orts to avoid the possibility of political bias by taking Yanai out of such an essential role, even when China refused to participate. Unfortunately, the court seems not to mind taking advantage of China’s absence, and the consequence is that politics triumphed over fairness and justice in its final ruling.

A China Southern Airlines plane landed on a newly constructed airstrip on Meiji (Mischief) Reef in the Nansha (Spratly) archipelago, July 13, 2016 PHOTO BY IC

Binding to Whom?

It came as no surprise that following the ruling, officials from several countries, including the US and Japan, pressured China to accept it. Because China has insisted it does not recognize the ruling, it is being framed as the party flying in the face of rule-based international order.

Ironically, the truth is that no major power has ever accepted an international court’s ruling when the case was related to sovereignty or national security interests. Some of the world powers that are urging China to accept the PCA’s verdict are the very countries who set these precedents.

For example, Nicaragua sued the US for supporting forces rebelling against the Nicaraguan government and for mining its harbors, bringing the case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1984. The US refused to participate in the proceedings, stating that the ICJ did not have the authority to hear the case. When the court rejected this claim, the US announced that it denied the ICJ’s jurisdiction on any future case involving the US, unless the US submitted the case. When the court ruled in favor of Nicaragua and ordered the US to pay the Central American country reparations in 1986, the US refused and vetoed six UN Security Council resolutions that ordered it to comply with the ruling.

There are a few more recent examples as well. One of them involves the UK, another country that has repeatedly called on China to obey the PCA ruling. In 2011, after the UK had established a Marine Protected Area (MPA) around the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, Mauritius brought a case to the PCA, contending that the UK’s actions violated UNCLOS. London disregarded the decision, and the MPA is still in place today.

In a 2013 case, the Netherlands sued Russia after the latter’s navy boarded a Dutch vessel sailing in waters o the Russian coast and detained its crew. Russia, like all other major powers, refused to participate, and initially ignored a tribunal’s order to release the crew. Moscow did eventually let the crew go after granting them “amnesty,” but it brushed o the PCA’s order to pay the Netherlands compensation for damage to the ship.

In light of these examples, China’s refusal to accept the ruling is the norm, not the exception. But if there is any major difference between these examples and the case brought by the Philippines, it is that the South China Sea dispute is far more complex and involves far more players. With so much at stake, no country, China or otherwise, would entrust a few individual judges with their national interests.

Even the Philippines appears to have had second thoughts about the PCA ruling. In April, Philippine President-elect Rodrigo Duterte said that he would only accept the verdict if it were in the Philippines’ favor.

By delivering an overwhelmingly one-sided ruling on an issue that involves massive interests and complex political rivalries, the tribunal has not defended the rule-based order of the region, but muddled it. Now, the nature of the dispute is increasingly turning into a zero-sum game, which will only lead to heightened confrontation and make it more di cult for relevant parties to negotiate mutually beneficial solutions.

To truly uphold international law, the parties involved should fulfill their “duty to negotiate in good faith,” a principle that is enshrined in the UN charter and given priority in the practice of international law. It is the only viable way to maintain stability and peace in the region, and to reach a solution that can be accepted by all parties.

Old Version

Old Version