NewsChina analyzes the impact of the Hague tribunal’s decision on the complex regional dynamics within the South China Sea

On July 12, the world finally heard the decision of a five-judge arbitral panel in the case of the Philippines v. China. The tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in e Hague ruled strongly in favor of the David in this David-and-Goliath story, concluding that China’s claimed historical rights within its “nine-dash line,” its proposed maritime border, have no legal basis. It also ruled that none of the geographical features in the Nan-sha (Spratly) island chain can be considered “islands,” which according to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) means that relevant parties cannot claim exclusive economic zones (EEZ) based on these landmasses. Leaders from around the globe spoke out about the ruling in the following days. Analysts have parsed their word choice and subsequent actions for hidden intentions and clues to next moves in order to examine the potential ramifications of the verdict.

Staying Tough

China immediately condemned the long-awaited ruling. The country has not been shy about its stance, frequently stating it would neither participate in the case nor accept its decision. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the ruling “null and void” with “no binding force” shortly after the tribunal announced its decision. In a 43-page white paper released by the State Council Information Office on July 13, China reaffirmed its historical right to the South China Sea within the nine-dash line. On July 13, China flew two civilian aircraft to the disputed Nansha/Spratly Islands’ Meiji (Mischief) Reef and Zhubi (Subi) Reef to mark the completion of the construction of each reef ’s airstrip. In the run-up to the announcement of the tribunal’s decision, China conducted massive, weeklong naval exercises near the Xisha (Paracel) Islands, which involved more than 100 naval vessels from all three of China’s major fleets. China’s air force announced on July 18 that it had conducted another round of air patrols over the South China Sea, which included sending an H-6K bomber over the disputed Huangyan Island (Scarborough Shoal). Moreover, China’s military announced that it would conduct another three-day drill in the South China Sea near its island province of Hainan on July 19. As the ruling is perceived as an international humiliation by the majority of the population, China’s tough responses aim to send a clear message to both the Chinese public and the international community: China will neither accept the ruling nor back down from its position in the South China Sea. In fact, on the day of the verdict’s announcement, an image created by the Party’s flagship newspaper People’s Daily of China’s “full” country outline, including the nine-dashed line, went viral on social media. The slogan below the map read: “China will not be one bit less.” Although its actions have been assertive, China has been careful not to overreach. For example, China has not declared an air defense identification zone in the South China Sea, as many had feared it would. China also explicitly rejected the notion that it would withdraw from UNCLOS, as some predicted. Moreover, China reiterated that it remains open to discussing this issue with the parties involved. “China stands ready to continue to resolve the relevant disputes peacefully through negotiation and consultation with the states directly concerned,” read a July 12 statement released by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Response

The reactions of the other parties involved were more mild than expected as well, particularly the US’s. Prior to the announcement of the tribunal’s ruling, the US had sent two aircraft carrier strike groups into the South China Sea, and there were reports suggesting that if the court ruled against China, the ships would enter the zone known as the “territorial waters” of reefs under China’s control, or the waters 12 nautical miles from the reefs’ shores. But apart from endorsing the ruling, the US reaction has been rather restrained. A US State Department press release issued July 13 said officials are “still studying the decision and have no comment on the merits of the case.” While Washington said that China and the Philippines should “comply with” the decision, it also urged all claimants to avoid provocative statements or actions. Although the Philippines came out as the case’s victor, it reacted cautiously to the news. Following the tribunal’s decision, Philippine Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr said the country “welcomed” the ruling, but called for “restraint and sobriety.” However, it is reported that a Philippine fishing boat ventured out to disputed waters near Huangyan Island/Scarborough Shoal, which analysts believed was aimed to test China’s position on the ruling. The boat was intercepted by patrolling Chinese vessels and told to turn around. The 10 ASEAN countries have been persistently divided on this issue, so they have not issued a joint statement regarding the ruling. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, whose views on this matter generally align with China’s, once accused the international tribunal of political bias. Laos is also known to sympathize with China’s position. Myanmar, for its part, issued a statement to urge ASEAN members states and China to resolve these disagreements with peaceful negotiation as stated in the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, which all of these parties signed in 2002. This position is closer to China’s as well.

At a forum to discuss the South China Sea arbitration case, former Taiwanese leader Ma Ying-jeou holds a bottle of fresh water collected at Taiping (Itu Aba) Island, emphasizing to attendees that Taiping/Itu Aba is the only feature in the region with fresh water sources. PHOTO BY CNS

More Lawsuits?

Some analysts have predicted that other claimants may be encouraged to le similar suits against China in the future as a result of the PCA’s overwhelmingly pro-Philippines decision, a trend which would weigh China down with more international pressure. But so far such a scenario seems very unlikely, as the benefits to the claimants would probably be limited. For example, Vietnam may find the PCA’s ruling may do more harm than good in terms of its own claims in the South China Sea. Currently, Vietnam occupies the most geographical features in the Nansha/Spratly Island region. Similar to China, its claims are not based on proximity (all of the features under its control are far beyond 200 nautical miles from its coast), but instead on a historical presence in the area. By rejecting the legal basis of historical rights claimed by China within the nine-dash line, the tribunal’s ruling has also effectively undermined Vietnam’s claim. Vietnam would gain nothing by taking China to court. That could be a possible explanation as to why Vietnam has been circumspect regarding the ruling. The day of the ruling, Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Le Hai Binh said Vietnam “welcomes the arbitration court issuing its final ruling,” without endorsing the decision itself. Adding that the country supports the settlement of disputes by peaceful means, Vietnam, like China, also reiterated its sovereign and maritime claims over both the Xisha/Paracel and Nansha/Spratly island chains. Malaysia, another claimant in the disputes, also showed little enthusiasm, likely because its disputes with China are less acute. None of the seven reefs controlled by China, upon which China has been conducting land reclamation and construction projects, lie within Malaysia’s claimed EEZ. As for its neighbor Indonesia, its disputes with China do not involve landmasses, rather parts of its EEZ overlap with China’s nine-dash line, so its response was also subdued. Both Malaysia and Indonesia have close economic ties to Beijing, so it may not be in their best interests to bring their disputes to court. In the wake of the ruling, both countries called for “restraint” and avoiding the use of force in the region. That leaves Japan as the country most likely to bring a second lawsuit against China. Indeed, Japan was one of the few countries that explicitly urged China to abide by the tribunal’s ruling after its announcement. Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida said that the tribunal’s decision is “final and legally binding” and that both China and the Philippines should comply with it. On July 14, Japan and the Philippines conducted a joint maritime drill in the vicinity of Manila Bay, widely interpreted as a show of force against China. Japan’s ruling party has even prodded Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration toward pursuing international arbitration over China’s drilling activities in the East China Sea. China and Japan disagree on where one country’s maritime boundary begins and the other’s ends. While Japan has argued to demarcate the maritime border using the median line that is equidistant from both landmasses, China bases its claim on the continental shelf. As their bilateral relationship deteriorated over the past few years, China built several oil rigs on the Chinese side of the median line, which China said is an undisputed region. Japan, however, has argued that the rigs have extracted resources from the Japanese side of the line. But on the other hand, Tokyo also has good reason to avoid a PCA case, as the tribunal’s ruling would likely damage Japan’s own maritime claim. In past years, Japan has claimed EEZs around a number of outpost reefs. The most controversial one is Okinotori, an atoll located more than 1,600 kilometers south of Tokyo. Although the rock is reportedly about the size of a small bedroom, according to the Washington Post, Japan considers it an island and claims a 200-nautical-mile EEZ around it. Both China and South Korea have contested this claim. Taiwan has been drawn into the fray as well. Earlier this year, a Japanese patrol vessel detained a Taiwanese fishing boat that was about 150 nautical miles from Okinotori, leading to a diplomatic row between Tokyo and Taipei. As the tribunal rejected the island status of all geographical features in dispute in the Nansha/Spratly Islands, the largest of which is tens of thousands of times larger than Okinotori, Japan has every reason not to bring a case to the PCA in the future because endorsing the PCA’s authority could cast serious doubt over the legitimacy of its Okinotori claim.

A pedestrian walks past a propaganda poster celebrating China’s South China Sea claims, Weifang, Shandong Province, July 14, 2016 PHOTO BY IC

Taiwan

Beijing’s one silver lining from the PCA ruling was a potential boost to the cross-Strait relationship. Taiwan and Beijing share many of the same South China Sea claims. In fact, Beijing’s claims originated from the so-called “11-dash line,” now more often referred to as the “U-shaped line” in Taiwan. The line first appeared on a map released by the government of the Republic of China (ROC) in 1947. When the ROC retreated to Taiwan after its defeat in the Chinese Civil War, it maintained its territorial claims to the South China Sea. When the People’s Republic of China took the ROC’s UN seat in 1971, it inherited the ROC’s territorial claim and developed the 11-dash line into today’s nine-dash line. In the meantime, Taipei continues to maintain its de facto control over Taiping (Itu Aba) Island, the largest naturally formed geographical feature in the South China Sea. Despite the rising tension in the region in recent years, Beijing has not challenged Taipei’s claim. On the contrary, Beijing has called on Taipei to work together to safeguard Chinese people’s common “ancestral assets.” Under the administration of Taiwanese leader Ma Ying-jeou, Taipei authorities laid claim to the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands, an island group in the East China Sea that has also been claimed by Japan. Prior to the South China Sea ruling, Ma made a high-profile visit to Taiping/Itu Aba Island to emphasize the ROC’s claim. He also invited journalists to tour the island to prove that it can sustain human habitation. However, Taipei seems to have backtracked from Ma’s position since Tsai Ing-wen, leader of Taiwan’s pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), assumed power in May. She has avoided mentioning the U-shaped line when discussing the South China Sea dispute and, just weeks before the PCA delivered its ruling, Tsai pulled back several navel vessels that had been patrolling around Taiping/Itu Aba. This led some analysts to suspect that Tsai would significantly change Taiwan’s policy on the issue by replacing the claim based on the ROC’s legacy with a more Taiwan-centric one. But the major obstacle for such a policy lies in the fact that Taiping/Itu Aba is over 1,500 kilometers away from Taiwan, making it difficult to legitimize its authority over the geographical feature without referring to the ROC legacy. It is believed that Tsai may have taken a gamble with the arbitration case. Taiping/Itu Aba was the largest feature involved in the case and has a comparably large area of 0.49 square kilometers. The feature sustains a military garrison, a hospital, a farm, a freshwater well and a temple. For these reasons, many in Taiwan believed that even if the PCA were to reject China’s nine-dash line, it would surely uphold Taiping/Itu Aba’s status as an island. If that had been the case, Tsai would have been able to have her cake and eat it, too. She would have been able to follow the US and Japan’s call to obey the ruling without sacrificing Taiwan’s interests in Taiping/Itu Aba, and at the same time she would have the legitimacy needed to abandon the ROC’s U-shaped line legacy. But the PCA ruled that even Taiping/Itu Aba is not an island, negating Taipei’s claim to its EEZ. The unexpected ruling immediately raised public outcry in Taiwan. Tsai’s office released a statement in response to the verdict: “We absolutely will not accept [the tribunal’s decision] and we maintain that the ruling is not legally binding on the ROC.” In essence, Tsai has taken a position that is similar to Beijing’s, a rare choice for the pro-independence DPP.

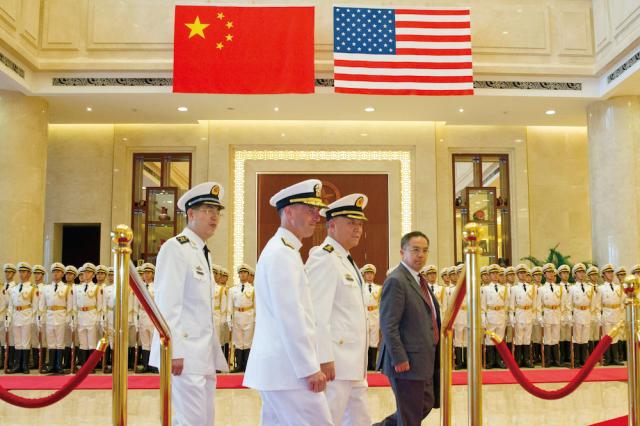

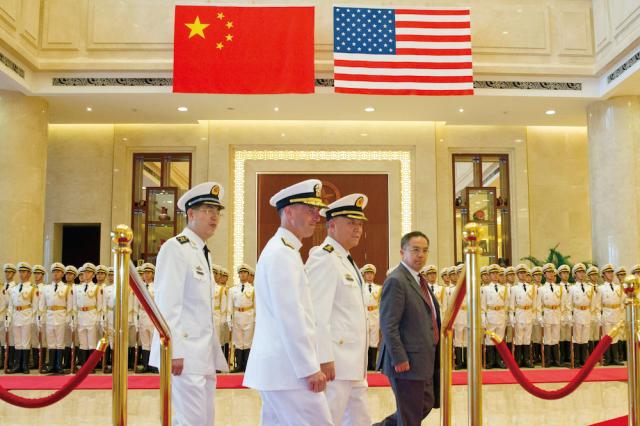

Wu Shengli, commander of the People’s Liberation Army Navy, receives US Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, July 18, 2016 PHOTO BY CFP

Going Forward

Given the complexity of the South China Sea dispute, it remains unclear how the tribunal’s ruling will influence regional dynamics in the long term. But as regional tension grows, e orts to ease strained relations between China and the US appear to be on the rise. On July 18, US Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson embarked on a three-day visit to China, where he met with Wu Shengli, the commander of the People’s Liberation Army Navy. Although both countries have persistently disagreed on maritime issues, they have both expressed interest in maintaining stability in the South China Sea. But as the China-US rivalry remains an underlying feature of the South China Sea dispute, its solution will not be found in a courtroom, but rather in the end to regional power struggles which will likely rage on for the foreseeable future.

Old Version

Old Version