Dao Lang ended his 20-year hiatus from music with a banger.

The 52-year-old pop singer’s song “Luocha Haishi” broke eight billion streams since its July 19 release, according to Tide News, a news app affiliated with Zhejiang Daily Press Group.

Its success came as a total shock to China’s entertainment world. Overnight, Dao Lang was trending online, where people celebrated the song for its sharp and satirical undertones.

Some fans meticulously analyzed the lyrics, claiming on social media to have decoded the song’s clever jabs at entertainment moguls for past slights and insults. Dao Lang has yet to address these claims publicly.

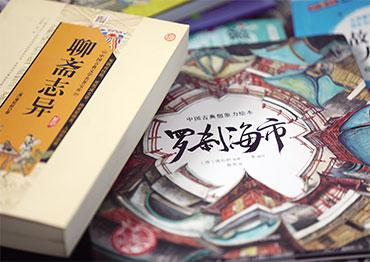

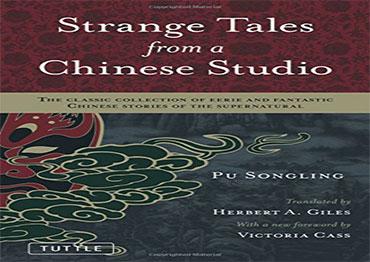

However, the origin of the song’s name is no mystery. “Luocha Haishi,” which means “Luocha sea market,” is a story in the classic collection Liaozhai Zhiyi, or Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, by Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) writer Pu Songling.

Pu was born in the city of Zibo, Shandong Province in 1640. He came from a relatively affluent family, and was the most studious of his four brothers. He gained the attention of Shi Runzhang, the superintendent of education in Shandong Province, a prominent figure in the literary world during the late 17th century, in the early Qing Dynasty.

At 19, Pu passed the initial round of the imperial exams known as the Tongzi Examination, achieving the top rank in all three levels of local government – county, prefecture and circuit, a promising start to his career.

However, Pu could never have anticipated the downturn his life would take. As his sisters-in-law squabbled over claims to the family property, Pu’s father became fed up and divided the household’s assets definitively. Pu and his wife received only a small portion of food, some barren land and a few dilapidated houses.

Undeterred, Pu turned his energy to studying for the imperial exams while working as a private tutor. At 31, Pu was briefly employed as an aide by Sun Hui, the magistrate of Baoying County, Jiangsu Province, who was from his hometown of Zibo. However, Pu soon returned home, finding an excuse to continue his career as a private tutor, a position of low status and meager wages, so he could keep trying for the imperial exams.

Despite numerous attempts over five decades, he never passed. It remained among his lifelong regrets. He funneled these feelings and experiences into his poetry and Strange Tales. His passion for writing was as fervent as his ambitions of officialdom. He began crafting Strange Tales in his youth, and completed it well into adulthood.

When Pu was 4 years old, a dynastic transition occurred. Amid invading armies sacking cities in southern China and peasant uprisings in Shandong, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) gave way to the Qing. The tumult led to events that inevitably influenced Strange Tales.

To gather more material, Pu opened a teahouse near his home, where he allowed patrons to pay for tea with stories. This clever approach amassed a wealth of tales that found their way into his compilation.

The collection took 40 years, encompassing much of Pu’s lifetime. However, upon completion, Pu lacked the means to publish. He sought an endorsement from Wang Shizhen, a prominent figure in the early Qing literary scene. Recognizing his exceptional talent, Wang readily composed a poem for Pu’s book. This nod from Wang sparked interest from publishing houses.

However, Pu’s book of ghosts, spirits and unconventional romance was just a bit too ahead of its time. Plus, Pu was an unknown writer. There were no guarantees the book would sell, and publishing was an expensive venture. No one wanted to take the gamble.

Pu battled poverty throughout his life, all while struggling with his Quixotic quest to pass the imperial exams as he continued to write. He passed away in 1715 at 75 years old, unfulfilled and unpublished.

But Pu’s book would posthumously solidify his place in literary history. For 50 years after his death, handwritten copies of Strange Tales circulated across China until 1766, when Zhao Qigao, a government official in Zibo, published the collection we know today.

Comprised of eight volumes, 491 tales and over 400,000 words, the collection stands as the pinnacle of ancient Chinese classical short stories.

Drawing from folklore, legend and historical anecdotes, the stories cover several genres. Romance constitutes the largest portion, where characters defy traditional feudal mores in the name of love. There are also stories that criticize the imperial exam system and the devastating effect it had on scholars, while others rail against the ruling class with biting satire.

Pu invokes ethereal creatures, like flower spirits and bewitching foxes, and imbues elements of the underworld with personality and social relevance to express his emotions, values and ideals.

In his work A Brief History of Chinese Fiction, Chinese literary giant Lu Xun (1881-1936) described Pu’s book as “the most famous among specialized collections.” Historian and author Guo Moruo (1892-1978) composed a couplet to display at Pu’s former residence in Zibo, praising his writing as “standing out in portraying ghosts and spirits, and penetrating to the core in its satirizing of greed and cruelty.” Famed novelist Lao She (1899-1966) noted that Pu had “infused characters into spirits and demons, and turned laughter and curses into literature.”

Pu alluded to his repeated exam failures in his stories. Many tales depict protagonists who face setbacks in their careers and resort to the invocation of supernatural forces to solve their problems or vent their frustrations. Additionally, the collection introduces a perspective on love at odds with its time, revealing that Pu had embraced modern views on romance.

The concise language of the collection makes it accessible to the reader, while its use of the supernatural captures the imagination. Coupled with its unique perspectives, the book has enjoyed sustained popularity since its initial publication. Its tales have even been adapted into films and television series that resonate with audiences today.

Among the popular stories from Strange Tales, “Luocha Haishi” is among the most well-known. It starts in the fictitious realm of Luocha, tens of thousands of kilometers from China. The protagonist, a merchant named Ma Ji, drifts to its shores, only to discover the inhabitants possess very strange facial features. The higher their social rank, the “uglier” they are. The prime minister, is described as having “inverted ears, three nostrils and eyelashes covering the eyes like curtains” – and locals find him handsome.

“Luocha Haishi” is a thought-provoking tale that offers a deep exploration of the human psyche and the choices individuals make when faced with the unknown and the alluring.

But according to some of Dao Lang’s fans, his song seems to reflect a particular theme in the tale: frustrations over unrecognized talent. Through the character Ma Ji, who makes himself appear ugly to win over Luocha’s ruler, Pu highlights the dark undercurrents of real-world politics. He illustrates how individuals often resort to any means necessary in their pursuit of fame and fortune, sometimes losing their true selves in the process.

However, Pu’s perspective on human nature was not entirely despairing. In “Luocha Haishi,” Ma Ji does not continue to wear his disguise. Instead, he departs from Luocha with a Dragon Prince who he meets at the titular sea market selling rare treasures. Upon arriving at the Dragon Palace, the king values Ma Ji’s abilities so much that he appoints him to a high position and weds him to his daughter, the Dragon Princess. Through this narrative, Pu expresses the hope that his talents might one day be appreciated by someone of importance.

Fans of Pu can learn more about his life at his former residence in Pujiazhuang Village, Zibo, Shandong Province. After his death, his descendants continued to live there. Though the original structure was damaged during the Chinese War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-1945), it was renovated in the early 1950s. The government-run Pu Songling Former Residence Management Committee then entrusted it to Pu’s 10th-generation descendant, Pu Wenqi.

In 1980, Zibo established the Pu Songling Memorial Hall, home to the Pu Songling Research Institute and Research Society. The hall has seven courtyards and eight exhibition rooms, covering an area of 5,000 square meters. And while no fox spirits, ghosts or citizens of Luocha have been spotted there yet, more than 100,000 visitors wander its corridors every year.

Old Version

Old Version