Most of China’s ancient paintings were stored in the Forbidden City (now the Palace Museum). During the Republic of China era (1911-1949), the last Qing emperor Pu Yi resided in the palace for over a decade and had the right to use its contents, including paintings and calligraphy.

However, he did not have ownership of them, nor did the government provide timely support for the preservation of cultural artifacts in the Forbidden City.

Pu Yi’s advisors devised a plan to bestow these precious cultural artifacts to his younger brother, Pu Jie. Paintings and calligraphy were chosen as they were valuable, easily portable, and inconspicuous compared to other items like gold, silver and jewelry. Over 1,000 paintings and calligraphy pieces were removed from the palace, though records vary as to the exact number.

Removing the artifacts had its advantages. The palace was prone to theft and fire, often perpetuated by its resident eunuchs, resulting in the loss of many calligraphy pieces and paintings. Those taken out by Pu Yi were fortunate to have survived.

After leaving the Forbidden City, Pu Yi moved to Tianjin and later became the puppet emperor of the Japanese-controlled Manchukuo in Changchun, Northeast China’s Jilin Province. He relied on these artworks to maintain his dignity and lifestyle.

In 1945, at the end of World War II, Pu Yi left most of the artworks in his regime’s palace, known as the Xiaobailou (Small White Building), and escaped with only a small portion. Today, it is known as the Palace Museum of the Manchurian Regime in Changchun.

The most valuable part of these artworks, numbering over 260 pieces, were said to have been carried out by Pu Yi himself. He intended to take them to Shenyang, Liaoning Province and escape to Japan by plane.

However, Soviet Red Army troops occupied Shenyang airport just as the plane was about to take off. Pu Yi and his associates were arrested, and the artworks were confiscated. They remained in China and were eventually handed over to the Northeast Museum, known today as the Liaoning Provincial Museum.

As a result, ancient calligraphy and paintings from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) can be found in three main collections: the Palace Museum in Beijing, the Palace Museum in Taipei (transferred by the Nationalist government to Taiwan), and the Liaoning Provincial Museum in Shenyang. Some paintings and calligraphy that initially were in the Liaoning Provincial Museum have since been transferred to the Palace Museum in Beijing, including the famous Northern Song painting Qingming Shanghe Tu, or Along the River During the Qingming Festival, by Zhang Zeduan.

The artworks that Pu Yi took to Shenyang were few compared to those left in Changchun. In the rush, dozens of crates containing calligraphy and paintings were abandoned in the palace of the Manchurian Regime. Pu Yi’s guards seized some of them, and many were later sold in markets in northeast China and Beijing. Some ended up in the hands of Nationalist Party officials.

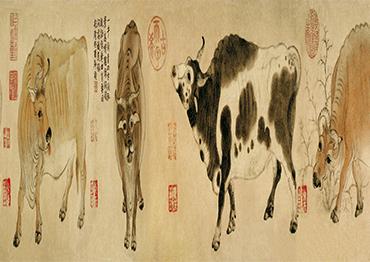

Qi Xu’s Grazing by the River was among the works that remained in Changchun. It was acquired by Zhou Juemin, commander of the Nationalist 25th Army Group. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Zhou’s name was included on the list of war criminals.

In 1983, Zhou’s wife, Li Qianyu, donated the painting to the Palace Museum in Beijing – ultimately returning it to where it came from.

Her donation coincided with the resumption of work by the Chinese Ancient Art Appraisal Group, making Grazing by the River the first painting among the 80,000 artworks the Group examined.

Grazing by the River was unanimously recognized as the only surviving treasure of Qi Xu. According to the Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings, a treatise on painting written during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Qi Xu produced 44 works.

For more than a century this artwork witnessed the turbulent changes in the nation’s history. It is now considered among China’s national treasures and is prohibited from leaving the country. On display to the public, its brilliant radiance shines once again.

Old Version

Old Version