In the past 70 years, China has made a successful transition from a planned to a market economy led by a series of reforms, behind which are the pains, joys and fates of ordinary Chinese

When Cheng Dongqing, a college teacher, is found earning extra money by giving lessons in his spare time and gets fired by his university, he is at a total loss. Before the ultimatum comes, his friend Wang Yang advises him to quit first. Cheng’s immediate reaction is “Quit the job? I’ll starve to death.”

Cheng is a character in 1992 in American Dreams in China (2013), a movie set against a period of great change as China transitions from a State-dominated economic and societal model, to one in which the market starts to wield more influence.

Cheng’s worry about starvation may seem exaggerated today, but it was a common concern at that time. Most people had a job provided by the State, referred to as an “iron rice bowl” – literally a job for life, where all your material needs would be taken care of. For the majority of urban residents, jobs were allocated in government departments, public institutions, education or State-owned enterprises (SOEs), referred to as work units. These were part of a planned economy in which the government made all economic decisions and took care of all economic sectors, including every aspect of an employee’s life. So losing an iron rice bowl job was considered lethal to people like Cheng who had no clue how to go about finding a new job, even if one existed.

But “the world has CHANGED,” Wang reminds Cheng. Former leader Deng Xiaoping made a famous southern tour in 1992 and visited the cities of Shenzhen and Zhuhai in Guangdong Province during which he made speeches pushing economic reform and opening-up, bringing his reform agenda back on track. Along with encouraging policies for entrepreneurship and the private economy, more and more people were encouraged to take the plunge and start their own business. Unlike Cheng, who is forced to start his own business, millions of people, who had a job for life but were not content with the status quo, voluntarily seized this new opportunity in search of a better life. Many saw great success, becoming the first of China’s new generation of tycoons. This includes Yu Minhong, founder of New Oriental, a private education provider who was the inspiration for the character of Cheng Dongqing and Jack Ma, founder of tech giant Alibaba.

The changing direction toward a market economy in the 1990s, as shown in the movie American Dreams in China, had its roots in the initial steps toward reform in 1978. Today, after 70 years of economic development, China has witnessed a successful transition from a centrally planned economy to a socialist market economy and an economic take-off in the new century.

It has been a long, difficult and slow process full of twists and turns, constant reflections and debates, reforms and backtracking. These are reflected in the joys and pains of ordinary Chinese whose fate is closely affected by every move the country makes, but who always try to adapt to the changes and find ways to earn a living crust or to realize individual values.

Earth-shaking Change

The People’s Republic of China was not a centrally planned economy right after its foundation in 1949. The earth-shaking land reform that changed the fate of Chinese peasants was depicted in The Earth (1954), a movie about the struggle for land against the landlords.

In 1950, the government issued a land reform law that abolished private ownership of land by landlords and guaranteed production autonomy to peasants. In urban areas, private business was also allowed, given the weak foundation of the national economy.

The transition to socialism eventually started in 1953, when the central government decided it was time to industrialize, prioritizing heavy industry and the socialist transformation of agriculture, manufacturing and capitalist industry and commerce. Private ownership was abolished in favor of collective and State ownership.

The agricultural sector was regarded as a major source of material resources and capital to develop heavy industry. The need to control the food supply, together with the demand for socialist transformation, helped collectivism to emerge.

In 1956 private ownership of farmland was abolished. Independent family farms were merged into bigger rural cooperatives to be farmed collectively. All land and production materials, including labor, were put under a cooperative, each consisting of several villages, with unified plans of production and allocation and members jointly engaging in farming activities.

Taking the land away from the owners was not easy, as shown in Huaishu Village (1962), a movie which depicts the challenges village leaders faced in the drive toward cooperatives. Some farmers wanted to work alone to get wealthy and were reluctant to hand over the land and join the cooperative.

In the winter of 1957, the government declared a nationwide realization of cooperatives in the rural areas. These cooperatives were merged into people’s communes during the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960) as subordinating production units, with multiple administrative functions covering every aspect of members’ lives. Every family depended on the collective for their livelihood. Individuals amassed work points depending on their labor, on which the distribution of food was based.

But it was easy to shirk one’s duties under this form of farming. As shown in the movie Li Shuangshuang (1962), some villagers had “selfish” ideas and behavior, like taking public property or playing tricks to obtain work points. Li Shuangshuang, the heroine and a village leader who always put the needs of the cooperative first, had to educate her fellow villagers to overcome their selfishness for the common good.

The disappearance of individual farmers, which put an end to a free market for agricultural products, meant there was no longer any need for private industry and commerce to exist. In 1955, Chairman Mao Zedong called for private businesses to prepare for “nationalization.” So capitalists of industry and commerce joined the transformation into a system of joint State-private ownership, in which the government took a share in a company and sent representatives to take charge of the private business. The transformation resulted in the nationalization of all private businesses. The new key enterprises became owned by the State and the collective. Starting in 1956, China began to build a system of SOEs, which were not only production units subject to administrative orders but also grass-roots organizations with broad social and political functions.

In the comedy Big Li, Little Li and Old Li (1962), for example, the meat processing factory depicted is a self-sufficient world. It not only provides a place of employment, but also dormitories and services like entertainment, cafeterias, a hair salon, healthcare and facilities for sports and education. It was a time when getting a job meant finding lifetime insurance.

Every individual in the urban area was knit into State-owned or collective-owned units that took care of every aspect of their employees’ lives from cradle to grave, just like each farmer was meticulously organized by the cooperatives. It was the complete realization of a centrally planned economic system.

Social resources were produced and distributed in a planned way. Following a system of planned purchasing and marketing, a certain allocation of agricultural products had to be sold to the government, at a lower-than-market price, and then were supplied, with ration plans, to citizens and farmers in need. In the 1950s, coupons for every necessity, from food to clothing, began to emerge. This coupon-dependent economy, that lasted until the 1980s, marked the State control of material supplies and was an important symbol of the planned economy.

Steeled for Industry

Audiences familiar with director Zhang Yimou’s movie To Live (1994), which traces the fate of a family through the birth of the PRC to the 1970s, might remember the scenes of the whole village smelting down their pots, pans and bicycles with enthusiasm in backyard furnaces, part of the Great Leap Forward campaign of the late 1950s. The whole country was mobilized to make steel, and every family had to hand over their ironware.

The Great Leap Forward, with impossible goals in producing agricultural products and steel, eventually led China into major economic hardship. As people were diverted from the land to produce steel, agricultural output dropped from 200 billion kilograms in 1958 to 143.5 billion kilograms in 1960, prominent Chinese economist Wu Jinglian wrote in his book Understanding and Interpreting China’s Economic Reform.

In the following years, until the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), there were several more efforts to decentralize power as China attempted reforms, all ending up with chaotic economic situations. The focus of system reform was then shifted to rural areas in the 1970s, with breakthroughs first made in collective farming, as demonstrated in the movie The Eighteen Handprints (2008).

In 1978, a new household responsibility system, where each farmer is assigned a plot of land and a target for a certain output, was trialed in Xiaogang Village, Fengyang County in East China’s Anhui Province when the province was suffering from drought.

The movie shows starving villagers from Fengyang running to other places begging for food. Out of desperation, the commune leaders of Fengyang decide to make Xiaogang a pilot project in which land would be distributed among smaller production teams of two or three households to try to stimulate the faded enthusiasm for farming under collectivization. The heads of 18 households in the village secretly distributed the land to each family by signing a “life and death contract” by pressing their handprints, driven by a desire to survive. This move broke the model of collective farming, then a risky choice politically as collectivism was considered inviolable. In 1979, the first year after the land distribution, Xiaogang’s grain output reached more than 65,000 kilograms, equal to the total output between 1966 and 1970, according to a report by the Anhui Daily in 2016. The Xiaogang experiment became a milestone in China’s economic reforms. In 1982, this form of farming was consolidated by a document issued by the central government. By the end of 1982, 93 percent of cooperatives had come under the household responsibility system, which indicated the successful decollectivization of Chinese agriculture. In 1984, total agricultural output reached a record 407.31 million tons, an increase of 33.6 percent over 1978, according to China’s

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

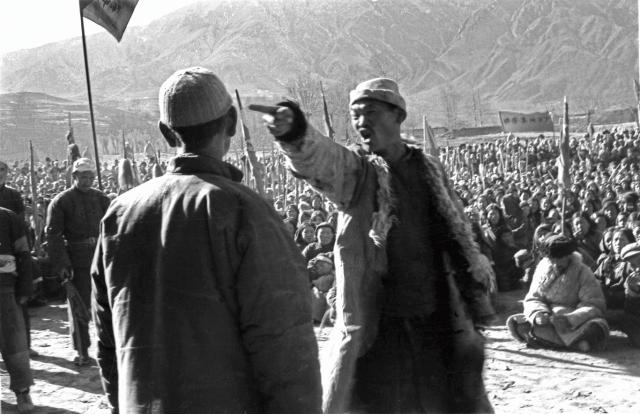

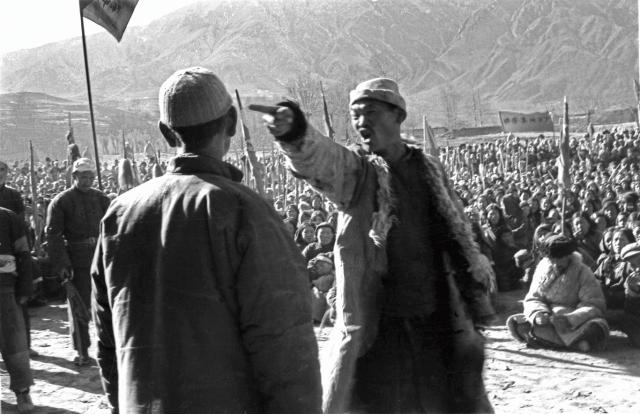

A scene of peasants denouncing landlords during land reform from The Earth

Farmers work in a cooperative in Li Shuangshuang

A Fengyang County leader encourages farmers to figure out flexible ways to improve efficiency in The Eighteen Handprints

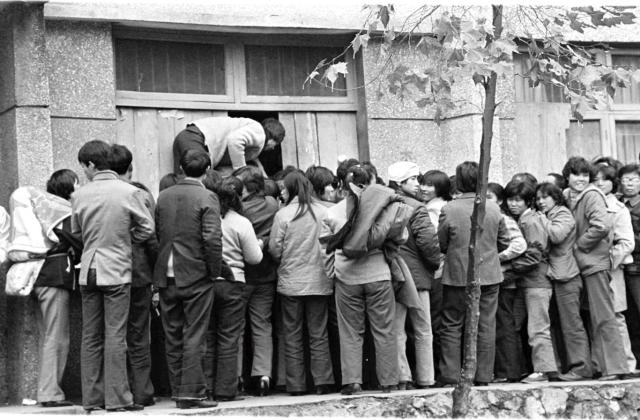

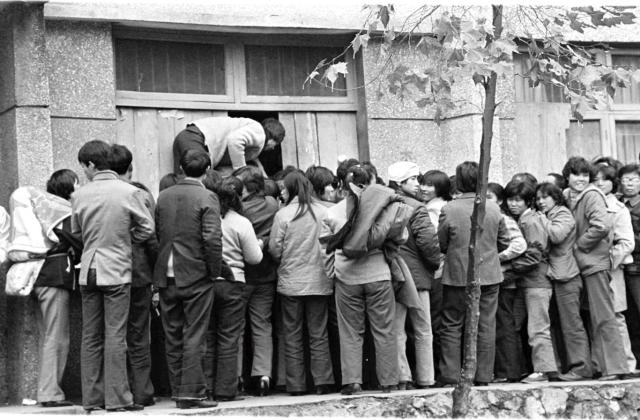

Residents in Shuicheng County, Guizhou Province wait for meat coupons, December 1987

An impoverished peasant argues with a landlord during the land reform campaign of 1951, Minhe County, Qinghai Province

People hand over all their ironware to make steel in backyard furnaces, Anyang, Henan Province, October 1958

Opening Moves

Xiaogang signaled the advent of a whole new era as the leadership under Deng Xiaoping launched China’s reform and opening-up policy in 1978. Meanwhile, the need for reform of SOEs grew increasingly urgent as the problems of administrative command grew prominent.

In a scene in the movie Blood Is Always Hot (1983) about SOE reform, a little boy cries desperately for a new radio, but his mother, who earns little at a State-owned textile mill which is seeing decreasing profits, sobs helplessly, underlining the urgency for reform.

But it was a hard process. In 1979, as reform and opening-up was pushed forward, China built four special economic zones (SEZs) in the south, adopting flexible economic policies in these zones to boost foreign investment and the economy. But people’s minds were yet to be emancipated and the rigid regulations of the old system were entrenched.

“China’s economic system is like a giant machine. Some of the gears rust and stop rolling,” the movie points out.

Luo Xinggang, head of the mill in Blood Is Always Hot, realizes the problem behind the decline in sales is that the mill does not produce what the market wants. He wants to make handcrafted scarves, but meets strong resistance, including from the administrative leadership. In this mill reigned over by administrative command, Luo does not even have the right to change the shell of a machine for an overhaul to improve efficiency. Hiring a designer is not allowed as recruiting new staff requires getting a quota from the relevant government department.

To stimulate initiative in the moribund SOEs, a round of reforms was started in the early 1980s to increase enterprise autonomy and give back a percentage of the profits to SOEs. The decentralization of power among SOEs is regarded as having allowed some to compete against non-State enterprises and improve their performance.

Meanwhile, the new mentality had largely invigorated society, enabling people the freedom to pursue their own happiness through hard work. In 1979, the government permitted licenses to be issued to the unemployed, some of whom were among the 15 million “sent down youth,” young people who were sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution who had now returned to urban areas. This allowed people to start individual businesses in repair, service and handicrafts, though hiring others was not allowed yet. Entering the 1980s, the private economy was encouraged as an important supplement to SOEs to drive the overall economy.

Thus emerged the bustling free market on the streets in Yamaha Fish Stall (1984), a movie about the rise of individual business-owners in Guangzhou. In the movie, crowds of people brush each other aside trying to choose what they want from the stalls, which reveal a wide variety of products in sufficient supply, from clothes to roast geese to fish ball noodle soup that could all be bought with money. All the seats are occupied in a restaurant at peak dining time, with customers savoring dishes with content expressions.

Most of the stalls are set up by jobless young people like A Long, who was once in jail and is encouraged to pursue happiness by opening his own fish stall. Individual businesses, once attacked as “remnants of capitalism” had become “a glorious thing.”

Between 1978 and 1990, China’s GDP grew by 14.6 percent on average, while the per capita disposable income of urban households increased by 13.1 percent on average, according to the Financial Yearbook of China.

Sink or Swim in the Sea

When Cheng Dongqing started his teaching business in 1992 in American Dreams in China, China was at a crossroads where the choice was whether or not to push forward reform, toward building a socialist market economic system, or not.

In 1988, China’s circulation system under the planned economy crashed as the government tried to liberalize price controls during a period when planned prices and market prices coexisted. This caused high inflation, which cast a shadow over the ongoing reform. In January 1992, Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour reaffirmed that reform and opening-up was unshakable, and this brought the reform back on track.

In October 1992, building a socialist market economic system was set as the goal of reform and opening-up, in which the market played a fundamental role in the allocation of resources under the country’s macro-control.

Deng’s reassuring speeches gave rise to a wave of entrepreneurship. In the 1990s, a large number of people with stable jobs in SOEs and government organs, including officials, quit to start a business, which was called xiahai, meaning jumping into the sea of market opportunities. In 1992 alone, 120,000 officials quit, according to statistics from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of China.

Many of today’s most successful Chinese entrepreneurs including Yu Minhong (New Oriental), Jack Ma (Alibaba), Liu Chuanzhi (Lenovo), Pan Shiyi (SOHO China) and Feng Lun (Vantone Holdings) were among the first to brave the new sea.

It is easy to imagine the hardship and challenges the first batch of Chinese entrepreneurs experienced in a just thawing market economy. In American Dreams in China, although the government supports private schools, Cheng encounters many challenges in obtaining a license, including gaining permission from the university that expelled him, underlining one’s remaining attachment to the collective.

It was not until 1997 that the obsessiveness over State ownership was removed and the private economy stopped being questioned ideologically, as a meeting of top lawmakers at the 15th National Congress of the Communist Party of China established a basic economic system based on public ownership together with other types of ownership. It also defined the non-public economy as a main component of a socialist market economy.

In contrast to the thriving private economy were the increasingly stagnant SOEs. In the early 1990s, a third of SOEs showed a deficit on their books. By 1997, the amount rose to over 40 percent, according to the Financial Yearbook of China.

The financial crisis in Asia in 1997 worsened the situation, which prompted the government to launch a three-year rescue and reform plan (1998-2000) to relieve the burden and improve efficiency. This aimed to deepen the reform of SOEs and build a modern enterprise system, a goal made in 1993 that features the separation of ownership and control rights.

About 40 percent of the 6,699 enterprises that were redundant constructions or with outdated production capacity, particularly in textile, steel and coal industries, were closed, merged or went bankrupt, according to a report from the Xinhua News Agency in 2000. Behind the reform lay the pain of millions of Chinese families, as between 1998 and 2001, 25.5 million SOE workers were laid off, according to the NBS.

The sudden change left millions of people, who had been dependent on SOEs for generations, in complete bafflement and with a feeling of abandonment. The collective crumbled and each individual had to go out to fight to survive. Under great financial pressure, quarrels, domestic violence and divorce were common. Small stands on the roadside selling goods or providing services like haircuts, which were once regarded as shameful tasks for SOE workers with stable jobs, grew common in many places, as pictured in The Piano in a Factory (2011), a movie depicting the lives of a group of laid-off workers in Northeast China after the steel mill they worked in for decades is closed.

In the movie, protagonist Wang Guilin organizes a small band to play at weddings or funerals to earn a living. “If you worry about being laughed at, you’ll never make a penny,” says Wang. Though in dire poverty, Wang hopes his daughter will be a pianist and he tries to make a piano with steel to win his daughter back from his ex-wife. The group of former SOE workers engaged in the scheme project a heroic but sad tone, with a strong reminiscence of their past collectivism.

The wheel of history rolls on. The pain of the changes comes to a climax as the crowds of laid-off workers helplessly watch the demolition of two chimneys at the mill.

By the end of 2000, a majority of SOEs had climbed out of financial difficulties as expected and many large- and medium-sized SOEs had reformed and built a modern enterprise system. From 1994 to the end of 1999, 2,016 of the 2,473 SOEs selected for reform had converted to a limited company system as defined by the Corporate Law, according to a People’s Daily report in 2000.

Yet the mass closures of SOEs since 1998 gave private enterprises the chance to grow by meeting market demand and recruiting laid-off SOE workers. The private economy’s contribution to China’s GDP was above 41 percent between 1998 and 2001, according to the Financial Yearbook of China.

Though controversial, the huge scale of reform has been recognized as a key step in revitalizing SOEs and the whole economy. It kept China competitive in the era of globalization and helped realize the sustainable rise of the Chinese economy from the dawn of the new century to today.

In November 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), a milestone in its reform and opening-up. In the following nearly two decades, China grew to be the second-largest economy, largest exporter and second-largest importer in the world.

Enterprises of various forms of ownership coexist in the socialist market economy. By the end of 2017, the number of private enterprises, which virtually did not exist before 1978, surpassed 27 million, and there were some 65 million individual business-owners, contributing more than 50 percent of the tax and 60 percent of the GDP, according to the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s top economic planning body. In the past 40 years, Chinese SOEs and private enterprises have become a force to be reckoned with in the global economy.

But challenges remain, for example, in providing a level playing field for SOEs and private enterprises, deepening SOE reforms and fixing lagging development in rural areas. Wider-ranging reforms are called for by economists to sustain China’s economic growth against a slowing GDP growth and complicated international economic situation. Since 2012, Chinese President Xi Jinping has stated on many occasions China’s resolve in deepening reform and opening-up, stressing there is no stopping the process.

“For our generation, the most important thing is to make changes and to have the courage to make changes,” Meng Xiaojun, another main character in American Dreams in China, cheers on his classmates. Though set in the 1990s, these words can still encourage people today when reform remains a solution to many problems in this land.

A Long and his friends sell fish at a bustling street market in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province in Yamaha Fish Stall

Laid-off worker Wang Guilin practises on a paper keyboard he drew to imitate a piano in The Piano in a Factory

Three Chinese entrepreneurs in the 1990s depicted in American Dreams in China

Laid-off workers attend free classes in skills such as cookery offered by employment departments, May 1997

Former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping tours Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, January 1992

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits an exhibition on the 40th anniversary of reform and opening-up, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, October 2018

Old Version

Old Version