Tensions over China’s disputes with the US and Japan are now landing on the agendas of international platforms like the G7

When foreign ministers of the G7 countries – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US – convened in Hiroshima on April 10 and 11, China became a major topic of discussion. The ministers issued a joint statement regarding the maritime disputes in the East and South China seas, saying they “urge all states to refrain from such actions as land reclamations” and “building of outposts... for military purposes.” Although the statement did not mention China directly, Beijing responded by summoning representatives from the G7 nations and warning them not to take sides in territorial disputes.

Tit for Tat Beijing’s rather strong reaction appears to stem from its anger and alarm over what many see as escalated and concerted efforts from the US and its allies to intervene in the conflicts surrounding the South China Sea.

US Secretary of State John Kerry (center), Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida (left) and British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond receive wreaths for placement at the Memorial Cenotaph at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, April 11, 2016

Just a few days earlier, on April 8, US Secretary of Defense Ash Carter canceled a planned visit to Beijing during a trip to Asia. However, Carter traveled as scheduled to the Philippines, which disputes China’s claims to the Nansha (Spratly) islands and Huangyan Island (Scarborough Shoal).

On April 14, shortly before he boarded a US aircraft carrier in the South China Sea, he announced that the US will start stationing warplanes in the country and had begun joint patrols of the South China Sea with Filipino forces in March.

The US and allied forces also conducted their annual joint military exercises in the Philippines, an event known as Balikatan, from April 4-15.

The drills, which involved about 8,000 troops, were widely interpreted as a show of force against China.

In the meantime, the Philippines and Vietnam, strategic partners as of last November, announced that they would explore possible joint exercises and naval patrols in the South China Sea.

The day after Carter’s April 14 announcement, China’s Ministry of National Defense released a statement that disclosed Central Military Commission Vice Chairman Fan Changlong had paid a visit to the Nansha/Spratly islands to inspect the cluster and its reefs. It did not specify the exact timing and location of Fan’s visit.

According to the statement, Fan greeted officers and soldiers stationed on the islands along with construction workers who are building different facilities there, including “lighthouses, automatic weather stations, oceanic observation centers and facilities for maritime scientific research.” While American media called Carter’s boarding of the USS John C.

Stennis aircraft carrier “a deliberate message to China on American power in the region,” as reported by ABC, Chinese State media has described the announcement of Fan’s visit as China’s response to that message.

This back-and-forth is just the latest example of the escalating tension between the two countries since the US launched its freedom of navigation (FON) operations to challenge China’s massive construction activities in the South China Sea’s disputed island groups.

In February, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s planned visit to the Pentagon was canceled during his trip to Washington amid increasing friction regarding Beijing’s deployment of advanced air defense systems in the region’s Xisha (Paracel) islands, which many experts believe is Beijing’s response to perceived escalated US provocation shown through the extension of its FON operation to the island cluster. Beijing considers the legal status of the Xisha/Paracel islands to be more settled than that of the Nansha/Spratly group, as China has controlled the Xisha/Paracels for more than four decades, with Vietnam being the only other claimant.

Regional Rivalry Apart from denouncing intensified military pressure from the US, Beijing also implicitly criticized Japan for its role in the G7 statement.

When he was explaining why China deemed the statement offensive and specifically directed at China, foreign ministry spokesperson Lu Kang said that “a senior official of one of the G7 countries mentioned that China needs to heed the voice of the G7.” That country is widely believed to be Japan, as Japan’s Kyodo News Agency had previously reported that Tokyo invited G7 foreign ministers to attend a meeting to hear concerns over “China’s construction work and military deployment in the South China Sea.” In contrast with official statements, Chinese media and experts have been more blunt. In a commentary written by Chen Yang, a PhD candidate at Toyo University, Japan “hijacked” the G7 meeting to serve its national interests. An editorial in the State-run Global Times claimed that Japan was trying to push its agenda during G7 gatherings because it is the only Asian country represented within the organization. The same editorial claimed that Japan lacks influence in other international bodies

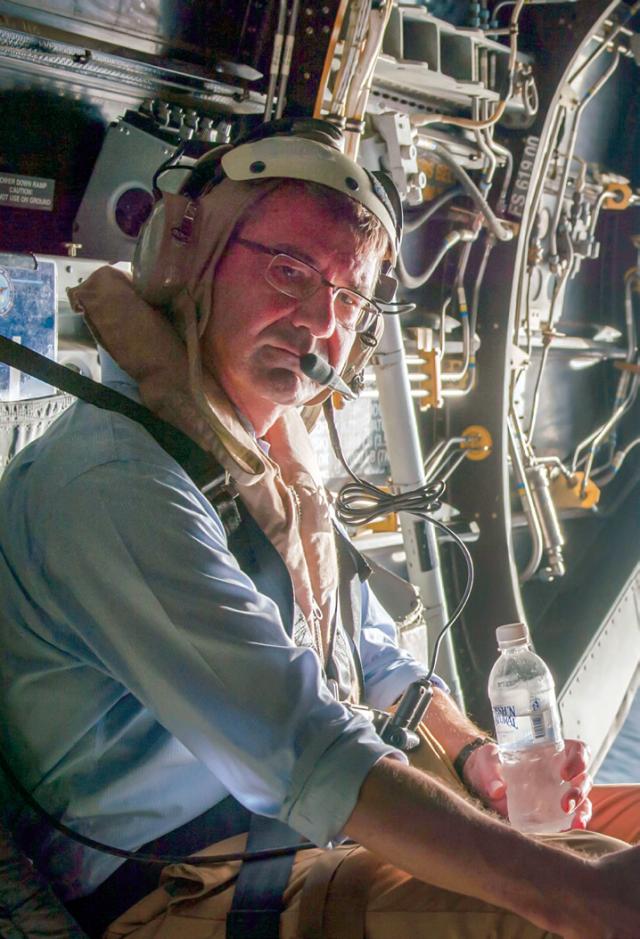

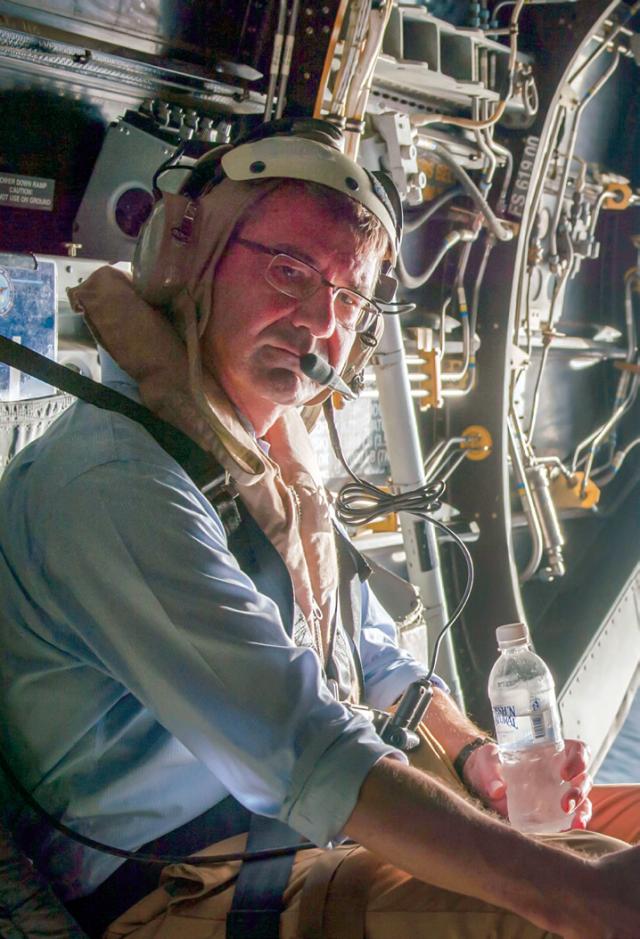

US Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter flies in a V-22 Osprey when visiting the USS Theodore Roosevelt, November 5, 2015

Just a few days earlier, on April 8, US Secretary of Defense Ash Carter canceled a planned visit to Beijing during a trip to Asia. However, Carter traveled as scheduled to the Philippines, which disputes China’s claims to the Nansha (Spratly) islands and Huangyan Island (Scarborough Shoal).

On April 14, shortly before he boarded a US aircraft carrier in the South China Sea, he announced that the US will start stationing warplanes in the country and had begun joint patrols of the South China Sea with Filipino forces in March.

The US and allied forces also conducted their annual joint military exercises in the Philippines, an event known as Balikatan, from April 4-15.

The drills, which involved about 8,000 troops, were widely interpreted as a show of force against China.

In the meantime, the Philippines and Vietnam, strategic partners as of last November, announced that they would explore possible joint exercises and naval patrols in the South China Sea.

The day after Carter’s April 14 announcement, China’s Ministry of National Defense released a statement that disclosed Central Military Commission Vice Chairman Fan Changlong had paid a visit to the Nansha/Spratly islands to inspect the cluster and its reefs. It did not specify the exact timing and location of Fan’s visit.

According to the statement, Fan greeted officers and soldiers stationed on the islands along with construction workers who are building different facilities there, including “lighthouses, automatic weather stations, oceanic observation centers and facilities for maritime scientific research.” While American media called Carter’s boarding of the USS John C.

Stennis aircraft carrier “a deliberate message to China on American power in the region,” as reported by ABC, Chinese State media has described the announcement of Fan’s visit as China’s response to that message.

This back-and-forth is just the latest example of the escalating tension between the two countries since the US launched its freedom of navigation (FON) operations to challenge China’s massive construction activities in the South China Sea’s disputed island groups.

In February, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s planned visit to the Pentagon was canceled during his trip to Washington amid increasing friction regarding Beijing’s deployment of advanced air defense systems in the region’s Xisha (Paracel) islands, which many experts believe is Beijing’s response to perceived escalated US provocation shown through the extension of its FON operation to the island cluster. Beijing considers the legal status of the Xisha/Paracel islands to be more settled than that of the Nansha/Spratly group, as China has controlled the Xisha/Paracels for more than four decades, with Vietnam being the only other claimant.

Regional Rivalry Apart from denouncing intensified military pressure from the US, Beijing also implicitly criticized Japan for its role in the G7 statement.

When he was explaining why China deemed the statement offensive and specifically directed at China, foreign ministry spokesperson Lu Kang said that “a senior official of one of the G7 countries mentioned that China needs to heed the voice of the G7.” That country is widely believed to be Japan, as Japan’s Kyodo News Agency had previously reported that Tokyo invited G7 foreign ministers to attend a meeting to hear concerns over “China’s construction work and military deployment in the South China Sea.” In contrast with official statements, Chinese media and experts have been more blunt. In a commentary written by Chen Yang, a PhD candidate at Toyo University, Japan “hijacked” the G7 meeting to serve its national interests. An editorial in the State-run Global Times claimed that Japan was trying to push its agenda during G7 gatherings because it is the only Asian country represented within the organization. The same editorial claimed that Japan lacks influence in other international bodies

Filipino police officers guard the US embassy in Manila following attacks by locals protesting the Mutual Defense Treaty signed between the US and the Philippines, January 20, 2016

such as the UN, despite applying to be named as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and is thus leveraging its G7 status instead.

The dispute between China and Japan over the East China Sea’s Diaoyu (Senkaku) islands seems to have quieted down in recent months.

However, the two countries may soon clash over the South China Sea, as Tokyo appears to have shown an interest in getting involved in those regional disputes.

Japan has been actively promoting its military ties with the Philippines over the past few years. Just one week before the G7 ministers’ meeting, three Japanese naval vessels, including a submarine, sailed to the Philippines.

The countries also held their first joint naval drills last year.

On top of the South China Sea issue, Beijing has been wary about the intentions behind Japan’s selection of Hiroshima as the meeting’s host city. The historical significance of the city, which became the site of the world’s first nuclear attack after the US dropped an atomic bomb on it in 1945, seems to some as being especially meaningful as the two countries have been butting heads not only on territorial and historical disputes, but on nuclear issues as well.

Going Nuclear During the UN Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons review conference held last year, Tokyo encouraged world leaders to visit atomic bomb memorials in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and attempted to record that invitation in the conference text, a move that was blocked by China.

According to Chinese Ambassador for Disarmament Affairs Fu Cong, emphasizing the suffering caused by the bombings without mentioning the circumstances surrounding them, including Japan’s wartime atrocities, serves Tokyo’s agenda “to portray itself as a victim of the Second World War, rather than a victimizer.” Therefore, when the G7 foreign ministers paid a visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park during the conference, it was to Beijing’s relief that US Secretary of State John Kerry, who was the first person in his position to visit the memorial and the city, offered no apology for the Allies’ 1945 decision to drop the atomic bomb.

Beijing interpreted Tokyo’s rhetoric during the meeting regarding nuclear disarmament as an attempt to highlight China’s nuclear arsenal, especially because the meeting was so focused on China. In contrast, China is worried about Japan’s nuclear ambitions.

China raised concerns earlier this year over the amount of enriched uranium and weapons-grade plutonium Japan is stockpiling. It is estimated that Japan has accumulated 11 tons of plutonium within its borders, with a reported 36 additional tons stored in Europe. Some experts believe that Japan has the capability to produce an atomic bomb within six months if it were to decide to do so.

In late March, Japan transferred 331 kilograms (730 pounds) of its weapons-grade plutonium to the US, in addition to a portion of its enriched uranium, but these amounts represent only a tiny portion of its total stockpile.

Remarks on the topic made by Japanese leaders have also caused China anxiety. A written statement released on April 1 by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s cabinet directly touched on the constitution’s Article 9, a critical clause outlawing war as a means to settle international disputes. Abe’s cabinet said this language does not prohibit the country from possessing the “minimum necessary level” of armed personnel needed for self-defense and makes no distinction between nuclear and conventional weapons when it comes to this requirement.

As China, the US and Japan become more entrenched in their positions on various issues, the stir caused by the G7 foreign ministers’ meeting may be just the precursor to further tension escalation.

Old Version

Old Version