Aside from the prevalence of sexual harassment, many graduate students are forced to meet the various needs of their supervisors and to essentially become their personal aids, resulting in a slew of social problems and controversies.

On December 26, 2017, Yang Baode, a PhD student at Xi’an Jiaotong University, was found dead. He is believed to have drowned himself after several years of alleged mistreatment by his supervisor. Yang’s girlfriend said Yang’s female adviser had regularly forced him to do work unrelated to academic research, including cleaning her room and car, doing her shopping and carrying her bags. What’s more, he was told by his mentor he had to arrive at a moment’s notice anytime before midnight, she said. The last straw was said to have been when Yang’s supervisor reneged on a promise to send him to study overseas.

Yang’s was no isolated case. Two years ago, a graduate student at Nanjing Post and Telecommunications University committed suicide by jumping to his death after long-term emotional abuse by his supervisor. Shortly afterward, a classmate said she was regularly harassed by the same mentor, and said she reported the situation to the university but was told to stay silent.

At most Chinese universities, students are given the right to change supervisor but in reality this is seldom possible. It is difficult for students to collect sufficient evidence of hardship before lodging a request, and if they are successful it is unlikely other supervisors will take on a “rebellious” student.

A third-year PhD student at a renowned university in Changchun, northeast China’s Jilin Province, told NewsChina that the university requires all PhD candidates to publish at least two papers in leading academic journals before graduation. After he had drafted two papers and handed to them his supervisor for review, his supervisor replied that the papers were garbage. Several months later, however, he was shocked to discover they had been published under his supervisor’s name.

“All PhD and master’s students under the supervision of my mentor are afraid to receive his call. Morality and research capacity go hand in hand. The behavior of supervisors hinges on their personal character, and I have been unlucky in this regard,” the student told NewsChina on condition of anonymity.

“I am always at the service of my mentor – either as an academic aid or a nanny. Most of the work has nothing to do with my own research. What I feel most embarrassing and unbearable is that I regularly have to help wash him when he is bathing,” he said. “I wanted to quit the program several times and I am not sure whether I can hold on. I can’t wait for graduation day.”

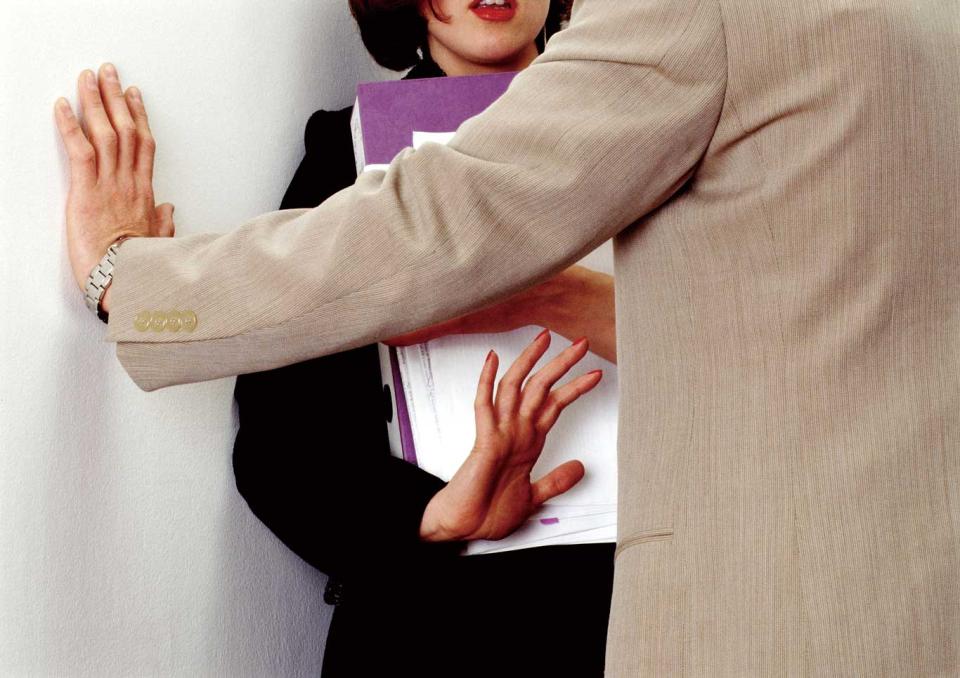

Over the years, supervisors in China have had a strong voice in determining graduate students’ dissertations, overseas study opportunities and graduation, placing students – particularly female students – at a disadvantage. Many of them have to endure in silent resentment.

Cao Chun, an expert on China’s higher education system at Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium, argued that the rampant sexual harassment on Chinese campuses stems from supervisors’ habitual abuse of power and a lack of oversight and control over them.

The PhD candidate added that Western universities have complete codes of conduct for supervisors and strict regulations prohibiting a professor from dating a student. Supervisors in China, however, tend to have the ultimate power to decide the fate of a graduate student. Rules must urgently be established that “put the power of supervisors in a cage,” Cao said.

“Supervisors in China play the role of agents of their universities, and directly exerted their power,” he told NewsChina.

“Graduate students form a relationship of attachment with their supervisors, making many supervisors greedy in their demands from students.”

Old Version

Old Version