All ICTY judges are elected by the United Nations General Assembly for a term of four years and are eligible for reappointment by the United Nations secretary general after consultations with the presidents of the Security Council and of the General Assembly.

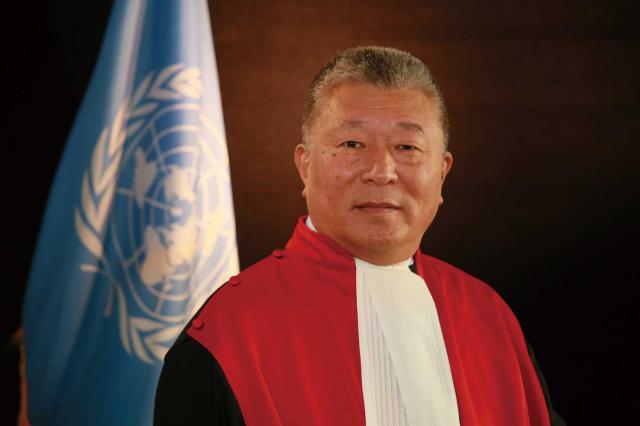

Liu Daqun, however, was directly appointed as an ICTY judge by the United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan in 2000. Wang Tieya was elected as a judge in 1997 but resigned in March 2000 due to poor health. At that time, the General Assembly was closed, and Liu was re-elected by the General Assembly in 2001 and 2004.

He described the role at the ICTY as heavy mental and manual labor, where he had to spend the majority of his time sitting, writing and reading. The court began at 9am and closed at 4pm, and judges had to sit for several hours on end.

In an article, Liu argued that the most appropriate age for an international judge was between 50 and 70 years old. “Judges under 50 tend to have weak qualifications and experience. Over the age of 70, however, they can find the physical strain of the trial too challenging,” he said.

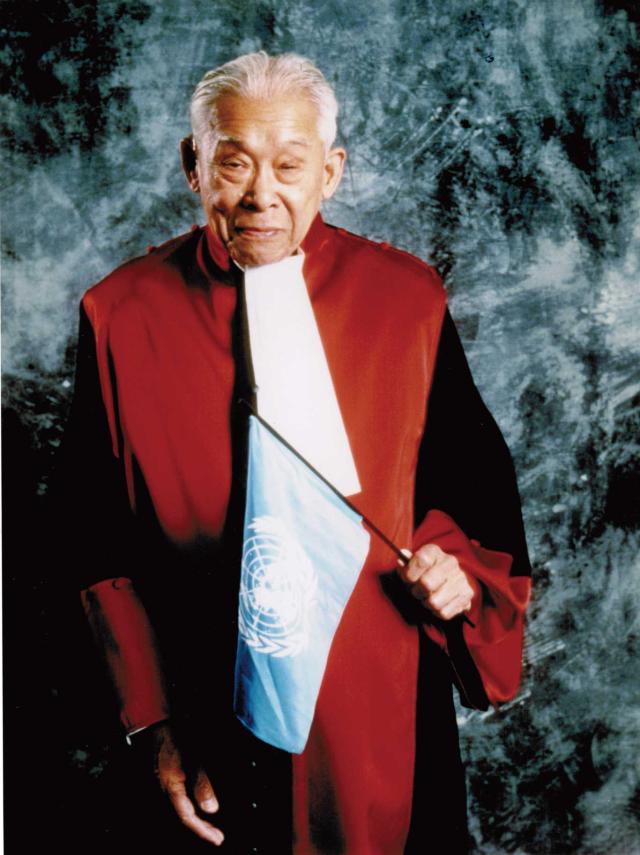

The average age of the first 11 ICTY judges was 60. When Li Haopei and Wang Tieya took their posts they were aged 87 and 84, and were the oldest judges on the tribunal.

Ling Yan, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law who is also the daughter of Li Haopei, told NewsChina her father had been dean of the law school of Zhejiang University since the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949.

Shortly afterward, the law school closed and China’s legal education suffered due to the nation’s own political turmoil, until China adopted widespread reforms in the late 1970s.

Li once appealed to the Chinese government, arguing that if the training of legal talent was suspended for too long, the nation would be left wanting. Since the 1980s when China rejoined the international community, it had to send a number of elderly legal experts educated before 1949 to serve as international judges.

Li Haopei once said he wanted to spend 10 years after his retirement writing a monograph on international private law and translate it himself into English. Wang Tieya expressed the wish to draft a textbook on international law. But neither ultimately managed to do so.

When Liu Daqun became the youngest ICTY judge at the tribunal, colleagues dubbed the then-50-year old an “infant judge.” Unlike his predecessors, Liu was educated after 1949 and graduated from Beijing Foreign Studies University in English language and literature and received legal training at China Foreign Affairs University.

Prior to his role at the ICTY, Liu held a variety of positions with China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Judge Liu Daqun was elected vice president of the ICTY by his peers on October 21, 2015.

Liu said even though China had made great gains in training international legal talent in recent decades, and the number of Chinese law school graduates each year matches the population of some small countries, very few could pass the recruitment examinations for the ICTY. As of March 2016, the ICTY employed 425 staff members of 69 nationalities, but only a handful of legal officers were from China.

In recent years, a growing number of Chinese students have landed internships at the ICTY. According to incomplete statistics, at least nine interns from China worked for the ICTY in 2016 and in 2017, the number rose to 11. In addition, the ICTY received two visiting scholars from China in 2017.

The ICTY did not pay interns, who had to cover their own costs. In an emailed reply to NewsChina, an ICTY spokesperson told our reporter that the ICTY had no partnerships with any Chinese universities or research institutes. Liu Daqun argued that in comparison, South Korea has sent interns to the Hague each year, as part of a program financed by the government to “enlarge the legal professional pool for international organizations.”

On August 1, 2017, the China Scholarship Council began to support college students to work as interns at international organizations. Some have already secured positions at international criminal judicial institutions.

Old Version

Old Version