A far-flung Qinghai Province locale has been picked to be the nation’s first official national park, but is this pilot project ready to launch?

The Angsai Township region teems with different species and plants / Photo by Wang Yan

Luo Zhu, a 43-year-old Tibetan nomad, lives in the remote pasturelands of Angsai Township in the western province of Qinghai. It’s a secluded life, but it’s not a lonely one; sitting inside his family tent on a late August day, he told NewsChina that a wide range of animals frequently wander near his home. He and his family members have spotted blue sheep, white-lipped deer, wild boar, Chinese mountain cats, Alpine musk deer, red foxes and, occasionally, even the elusive snow leopard. “At sunset, sometimes large herds of blue sheep come down from the mountains and drink water from the stream,” Luo said, pointing at the Zhaqu River offshoot that flows a few meters from his home.

Luo’s tent is tucked in a deep valley, surrounded by rust-red canyon walls reminiscent of the landscapes of the American southwest. Water flows quietly in the nearby Zhaqu River before feeding into the mighty Mekong, which nourishes more than 60 million people downstream.

Now local officials and residents want to share Angsai’s vistas with the world. Over the past three years, China’s central government has been pushing toward creating a national park system. Because of several factors, such as Angsai’s remarkable biodiversity, it has been selected to be a guinea pig for the country’s national parks. Angsai park managers hope to combine conservation science, local participation and eco-tourism to outline a blueprint for China’s parks to come. Although this name has yet to be approved by the central government, this pioneer project is known locally as Angsai National Park.

Initiation

Although China boasts about 10,000 protected areas, it lacks a unified system to regulate and safeguard these regions. The central leadership has recently begun to push for the establishment of a national park system in the vein of those in Western countries. In June 2015, the central government announced nine pilot national park projects to be launched across the country. Many of these areas have already been cordoned off as protected areas, but will soon become the country’s first official national parks.

One of these pilot park areas will be in a 123,000-square-kilometer region within Qinghai Province’s Sanjiangyuan Area. “Sanjiangyuan” means “source of three rivers.” The headwaters of the powerful Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong rivers all flow from this region, which provides 15 percent of the Mekong’s water discharge, 25 percent of the Yangtze’s and 49 percent of the water surging in the Yellow River.

Last April, the Qinghai provincial government divided up this pilot park area into three subareas, which will eventually be individual national parks. Angsai, together with another four towns within the greater area of Zaduo County, has been set aside as the Mekong River sub-area. Once the future Mekong River National Park officially opens its gates, the Angsai National Park will become a part of this larger site.

While in this context Angsai is just a two-dimensional outline on a government map, on the ground, it is full of life. The approximately 2,000-square-kilometer expanse of land is not only home to Tibetan nomadic herders like Luo Zhu, but also a notably diverse range of wildlife grazing on alpine meadows, crawling over bare rocks and padding through thick forests, all at an altitude of about 4,000 meters.

“Brown bears have visited our house a few times when we weren’t home,” Luo told our reporter. “They destroyed the tent and ate our food.” In spite of the fact that Luo loses about three to five cattle annually to the appetites of hungry snow leopards or wolves, he said the wildlife doesn’t frustrate him. “We’re used to living with them, and our children like to see animals around,” he said.

Luo Ji, a 26-year-old woman who lives a few miles uphill, told our reporter that in August, a snow leopard slaughtered a young yak on the mountain slope just behind her family tent. But this was just part of Qinghai life. All of the locals interviewed said they are used to cohabiting with animals.

Due to the remoteness and the local Tibetan people’s relatively environmentally friendly way of life, Angsai and the surrounding regions have maintained a fairly intact ecosystem, unscathed by the development that has transformed much of China over the past few decades. That is why the silver fur of the endangered snow leopard is still seen near human settlements in this area. Earlier this year, Angsai-based infrared cameras captured the world’s first footage of the snow leopard mating process. “This shows that there is a healthy breeding population in the region,” Lü Zhi, a conservation and biology professor at Peking University, told domestic media in a late April interview.

In Tibetan culture, spotting a snow leopard is a blessing. It is a sacred animal in their eyes. As a result, a significant number of herders actively participated in local wildlife preservation initiatives, which included anti-poaching projects, camera trap installation, environmental monitoring and litter removal. According to the nongovernmental Shanshui Conservation Center (SCC), 13 snow leopards, three leopards and 11 other carnivorous species have been captured on Angsai cameras. “So far, statistics indicate that Angsai is one of the most thriving habitats for snow leopards and that it has the most comprehensive carnivore population in China,” SCC’s Zhao Xiang told NewsChina.

Ni Ga, a member of the Mekong River National Park management bureau and head of Zaduo County land and resources bureau / Photo by Wang Yan

Vultures eating the dead horse body by the roadside to Angsai / Photo by Wang Yan

Public Involvement Zaduo County Party Secretary Tsedan Druk told NewsChina that Angsai National Park will aspire to a conservation and development model that combines public participation with scientific research. Zaduo has invited experts from different fields to help plan for the park’s official launch. These have included NGOs like the SCC to conduct surveys of biological resources, rafting experts to establish rafting areas, geologists to research rock formations, eco-tourism experts to develop the park’s tourism appeal and indigenous folklorists to gather and compile local cultural resources. ��

To weave in the local community, Zaduo began executing a plan in July to hire a park ranger from each of the region’s households. Officials aim to hire more than 7,000 part-time rangers by the end of 2017, with each one given a monthly stipend of 1,800 yuan (US$270). In 2014, the average full-time monthly wage in Qinghai was 1,859 yuan (then US$300). “Appointed rangers are responsible for tending to the pastures and wetland areas, monitoring the wildlife and picking up litter within the national park area,” continued Tsedan. “This will directly benefit locals by increasing their household income by a significant amount.”

In August, Zaduo County and the SCC co-organized an event in what will become Angsai National Park. They invited about 40 nature lovers to participate in competitions like birdwatching and nature photography at the county’s expense. The purpose of the event was twofold: it was a practice run for the park’s eco-tourism functionality, as well as a quick way to survey the region’s flora and fauna. According to Buni Ma, the head of Angsai Township, over 300 locals were directly involved in the event. An inside source told our reporter that Zaduo County had invested as much as 1 million yuan (US$150,000) on the four-day experience.

Buni said the format of this event mimicked the activities Angsai National Park will offer in the future. “In the past few months, we have had tourists come to raft along the Mekong River as well as observe and photograph wildlife, and the local government has actively supported these events both financially and logistically to test the feasibility of these tourism models,” Buni added.

Tibetan nomads in the local community have been enthusiastic about the development of the national park project, which is a crucial element to the park’s success. Terry Townshend, a British birder based in Beijing who was invited to the Angsai park event, agreed with the park’s eco-tourism model and emphasized that “public participation can really save species.”

Tsedan Druk stressed to our reporter that park officials hope Angsai’s structure will be imitated in other pilot parks around the country. “Through combining the local community’s participation, general public involvement, government guidance and the support of scientific institutions, we are practicing a national park format… that is reproducible,” Tsedan said.

Various sources said Angsai’s brand of eco-tourism may end up targeting high-end consumers to limit the area’s number of annual visitors and thus better protect the environment.

“In my opinion, we should go to [the small neighboring country of] Bhutan to study its eco-tourism management measures and achievements so that we can restrict the number of visitors entering the park and better preserve it, while still increasing the local community’s income,” added Ni Ga, a member of the park management bureau.

Mixing Management

As a pilot project, Angsai National Park has garnered nationwide attention. In late August, during a Qinghai Province visit, Chinese President Xi Jinping held a video conference with Angsai officials and rangers. Xi stated that Qinghai “must give the development of an ecological civilization a prominent position in the local development landscape,” adding that it is vital to “respect nature, adapt to nature and protect nature.”

Compared to the fragmented management of China’s current protected area network (see “System Overhaul,” NewsChina, Volume 095, July 2016), Angsai National Park has formed an integrated management system with personnel distinct from other government departments, such as the water resource department and forestry department, Tsedan said. “Now the management bureau for the Mekong River National Park subarea [comprising Angsai and four other Zaduo County townships] has been established, and it consists of 48 staff members who will enable us to manage the ecological protection of the whole area more effectively,” Tsedan added.

This practice of separation was endorsed by Yang Rui, head of Tsinghua University’s landscape architecture department and one of the experts appointed by the central government to advise on the nascent national park system, during an interview with NewsChina in mid-May. Yang confirmed that the management bureau personnel in the Sanjiangyuan Area parks would be kept separate for the sake of untangling the intertwining interests among different government departments within a protected area. In Yang’s words, this is a rare effort among the pilot national park projects.

However, through interviews and observations, NewsChina found this separation of interests is at present only true on paper. The Zaduo government is still in full administrative control of Angsai National Park’s management bureau, the overarching Mekong River National Park management bureau. All 48 of the current staff members have ties to the local government.

For example, Tsedan Druk is not only the Party secretary of Zaduo County, but also the Party secretary of the Mekong River National Park management bureau. Ni Ga is concurrently a member of that management bureau and the head of the Zaduo County land and resources bureau.

In reference to himself and his fellow park management bureau members, Ni said: “We have dual roles, and this really is inhibiting our work within the national park system. At this point, the national park project cannot run without the county government’s approval.”

In addition, park managers are dealing with a legal vacuum. New laws to regulate and protect the fledgling national park system have yet to be passed, so managers are limited to utilizing existing laws regarding protected areas. The establishment of the Angsai park will effect one positive legal change, though, according to Ni, because having a national park within the region effectively prohibits some mining activities that otherwise might be allowed in the area.

A deserted monastery inside the Angsai park’s borders / Photo by Wang Yan

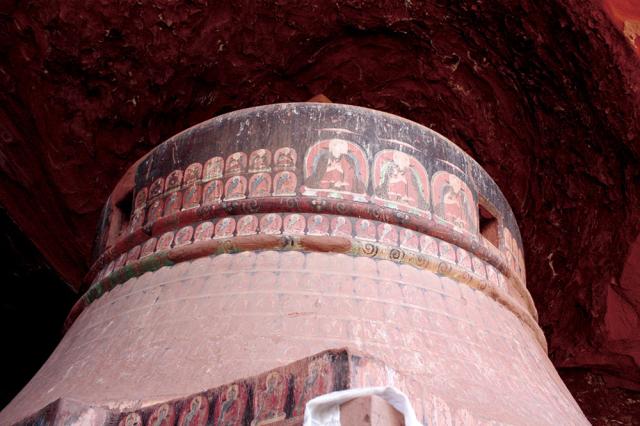

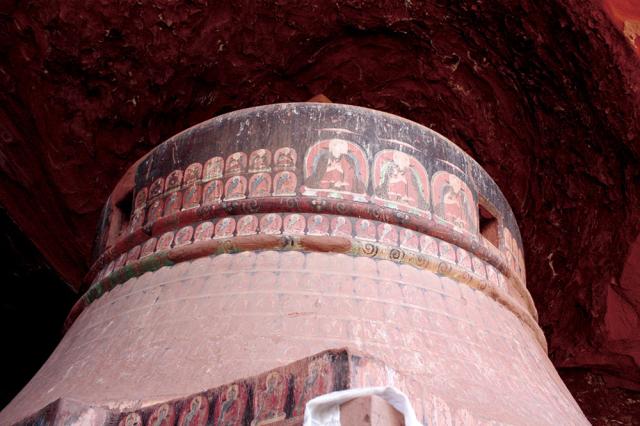

Ancient Buddhist scriptures and relics from a looted pagoda lie scattered near the destroyed structure / Photo by Liu Sunan

An intact Angsai pagoda with more than nine centuries of history / Photo by Wang yan

Cultural Loss Luo Zhu is raising four horses and over 40 yak on the Angsai pasturelands, but he told NewsChina that this small herd is nothing compared to what his family tended in the 1990s. “We used to have 100 sheep, 50 goats and over 120 yak on the same pastureland, but now most of our income comes from gathering cordyceps, so we don’t need as much livestock,” Luo explained, referring to the pricey caterpillar-shaped fungus that is considered very valuable in traditional Chinese medicine.

Because of the increase in income from collecting cordyceps, more and more herders in Angsai and the surrounding area have given up their traditional nomadic way of life, sold their livestock and abandoned their pasture tents for homes in more developed areas. Development is popping up – a dirt road that was finished in 2013 slashed the travel time between the pasturelands and the Zaduo County center, turning the trip from a two-day horse ride to a two-hour bumpy drive.

But as money steadily trickles into the area, cultural and religious traditions appear to be flowing out. Most locals interviewed by our reporter admitted they no longer frequent monasteries nor make donations to monks, an unusual trend compared to most other Tibetan communities. This isn’t the only tradition that’s fading. According to Tibetan Buddhism, one cannot hunt or disrespect nature in any way on what is considered a sacred mountain, but Angsai locals explained that this is no longer quite as strong a taboo.

The only monastery near Luo Zhu’s family tent has more than 900 years of history, but its last two monks left more than a year ago. Three ancient pagodas around the monastery have either collapsed or are on the brink. One of them was looted by thieves in 2014, and now some ancient Buddhist scriptures and relics remain scattered in the vicinity, with no efforts made to preserve them or their former home. Sonam Dhargay, a volunteer Angsai park ranger, admitted to the reporter that without special protective measures in place, the past two years’ influx of tourists worsened the pagodas’ already endangered condition.

Tashi Samge, a Tibetan monk and environmentalist, expressed concern over the area’s future development. “In Angsai, an area rich in culture and art that has thousands of years of history, preserving indigenous culture is just as important as preserving the national park’s flora and fauna,” he said. “I don’t know what our national park will be like in the future, but one thing is certain as far as I am concerned: If there are no more monasteries and monks in the region, and the herders have also moved away, the valley will be dead, even if the number of brown bears and snow leopards increases.”

Ni Ga shared similar worries about locals’ future. “Once the cordyceps bubble collapses, [local Tibetans] who have abandoned their pastureland and nomadic lifestyle will have other no means to make a living,” he said. “At that point, who can ensure that they will not resort to exploiting wildlife resources?”

Mekong River National Park in Qinghai Province

Old Version

Old Version