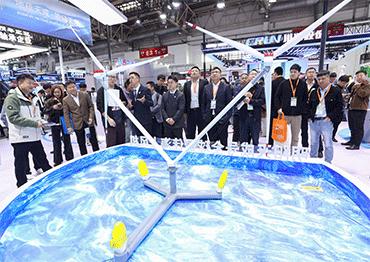

At Lindong New Energy’s headquarters in Binjiang District High-Tech Zone, Hangzhou, an exhibition hall collects real-time data from LHD generator sets. During a July visit, the reporter saw via surveillance cameras that the underwater turbine, stationary at low tide, started rotating and gradually accelerated as the afternoon tide rose.

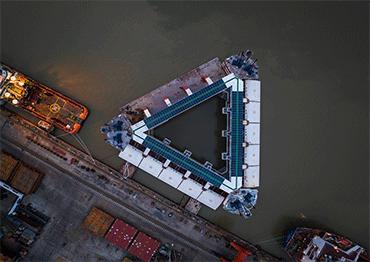

Construction of the second phase of the project began in 2018, followed by the 2022 launch of the 1.6 MW fourth-generation tidal current turbine called Fenjin (Endeavor) – a milestone as the world’s largest single-unit tidal current generator to successfully generate power and be connected to the grid.

“On this single day, this unit’s peak power generation is 1,317 kW, with cumulative output of 3,804 kWh. Power output ties to tidal periodicity, one peak lasts about six hours, with two peaks daily,” Lin Dong, chair and chief engineer of Hangzhou Lindong New Energy, told NewsChina.

The Endeavor power generation unit has so far accumulated over 5.5 million kWh of electricity. After LHD’s first-generation 1 MW unit was connected to the national grid in August 2016, following tech upgrades, the second and third generations followed in 2018. The third-generation unit remains in operation, generating over 1.3 million kWh cumulatively in more than six years.

Shi Hongda, director of Ocean University of China’s Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Marine Engineering, told NewsChina that ocean energy includes tidal energy, tidal current energy, wave energy, ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) and salinity gradient energy.

Tidal energy uses the rise and fall of the tides to power generators, tidal current energy generation is similar to wind power as it uses devices placed directly in the current to generate power, and wave energy uses devices that exploit the kinetic energy of the tides, using a buoy containing a generator loosely tethered to the seabed. Engineering practices are underway for these three, Shi said.

In the case of the latter two processes, OTEC exploits temperature differences in ocean layers in tropical areas to power generators, and salinity gradient energy, also known as blue energy, uses the difference in salt levels between fresh and salt water. When salt and fresh water are mixed through osmosis, energy is released.

Shi added that tidal power usually needs dams to use internal-external water level differences, and large bays must be enclosed to boost water flow to allow substantial output. “China has dense coastal populations. Though tidal energy has reliable principles and mature tech, its development doesn’t fit the national conditions,” he said. Enclosing coastlines for it would affect other marine projects in most areas, so tidal energy is not a key R&D focus in China.

Unlike tidal energy, tidal current energy projects are usually sited in inter-island straits with high water flow and have less impact on offshore human activities. Professor Liu Hongwei at Zhejiang University’s School of Mechanical Engineering told NewsChina that tidal current energy is highly regular, and its turbines can draw on wind turbine technology as their use is similar.

It is also less affected by offshore weather. Lin Dong noted that despite being hit by three typhoons in July, the LHD project’s daily power output fluctuated by less than 10 percent, and was not interrupted.

In 2009, Lin Dong, who holds master’s degrees in business administration and energy development and management, founded LHD Technology in California with fluid mechanics expert Huang Changzheng and new materials expert Ding Xingzhe. The “LHD” abbreviation comes from their surnames’ first letters, and the company focused on tidal current energy research. Lin invested US$500,000 annually to explore tidal current energy power generation technical routes at first, conducting many experiments in an in-house circular water channel nicknamed the “swimming pool.”

“Tidal current energy power generation was a cutting-edge field at the time, with no country having fully established a technical path,” Lin said. The UK installed SeaGen, the world’s first commercially grid-connected tidal current generator (1.2MW), in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland, in 2008. It was decommissioned in 2016 and replaced by more efficient turbines.

Shi Hongda noted that northern Europe has the world’s richest wave and tidal current energy due to differences between tides and favorable ocean currents. Though China has vast sea areas, it lacks resource advantages due to low energy flux density – a measure of energy passing through a unit area per unit time – which is limited as it lacks areas with strong tides. This means its tidal current energy utilization needs more advanced technology to generate power under low flow velocities. China’s exploitable tidal current energy has a theoretical average power of nearly 14 million kW, over half of which is in Zhejiang Province.

In 2012, Lin led the LHD R&D team back to China and invested 200 million yuan (US$28m) to develop the Zhejiang LHD Marine Tidal Current Energy Power Station on Xiushan Island, the country’s first tidal current energy power station.

Liu Hongwei’s team has researched tidal current energy power generation technology since 2004. In 2014, they built 60kW, 120kW and 650kW tidal current energy units on Zhoushan’s Zhairuo Mountain Marine Science and Technology Demonstration Island, and also constructed China’s first floating tidal current energy test power station.

Old Version

Old Version