Following the Mukden Incident – a false flag operation in 1931 that Japan used as a pretext to launch its invasion of China, the Japanese military occupied the area of Northeast China then called Manchuria.

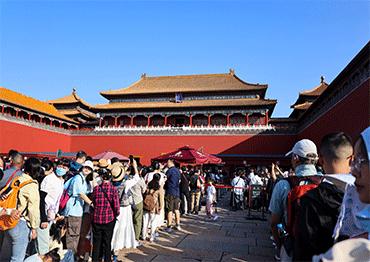

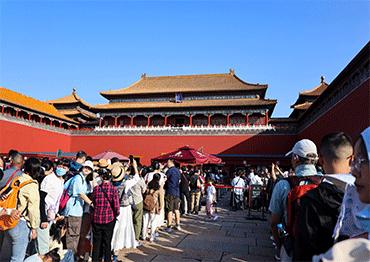

Soon after, they set their sights on Beijing, particularly the vast collection of priceless cultural artifacts housed at the Palace Museum, a huge complex located in the heart of the city and former home to Chinese emperors known as the Forbidden City.

Having failed in an earlier attempt to loot cultural relics during the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894, they came better prepared this time. The future of China’s most prominent museum and its vast collection hung in the balance.

Panic spread throughout Beijing. The city’s residents were still haunted by memories of the 1860 looting and burning of Yuanmingyuan, or the Old Summer Palace, by Anglo-French Allied Forces during the Second Opium War.A tough decision had to be made: Should the Palace Museum’s collection be evacuated?

The museum’s board of directors convened urgently to discuss the feasibility of such a plan, but no consensus was reached. It was Ma Heng, deputy director of the museum’s antiquities section, who proposed an immediate evacuation of the collection to southern China. He emphasized that the priority was to protect the relics from falling into enemy hands, even if it meant the future return of these treasures to Beijing would be uncertain.

Ma’s proposal sparked public outcry. Critics accused him of valuing objects over the well-being of people and the nation. Among the detractors were prominent figures like Hu Shi, a renowned diplomat and scholar, and Lu Xun, a prestigious writer and literary critic. In a poem, Lu Xun lamented, “The capital stands deserted, a hollow, lonely shell, while in frantic haste, the antique treasures were shipped away.” Even Ma’s son, Ma Yanxiang, believed the relics should be sacrificed, if necessary.

Others organized protests. Zhou Zhaoxiang, the head of the Institute of Antiquity Conservation, banded together with other commercial and civil organizations in an effort to reverse the decision. They argued that moving the relics would be too risky, and that by evacuating the collection, Beijing would be surrendering without a fight.

As expected, Japan declared its intention to seize the Palace Museum’s collection, claiming that the Kuomintang government was no longer capable of safeguarding the relics. Japan also promoted the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” and enforced the inclusion of Japanese history and language in schools under its control. Culture thus became a focal point of the war.

At this critical juncture, Ma Heng consulted with the museum’s president, Yi Peiji. Together, they telegraphed the Kuomintang central government, then based in Nanjing, briefing the country’s leaders on the urgent situation.

While awaiting a response, Ma Heng and Yi Peiji decided to act. They instructed museum staff to begin packing each item with the utmost care, ensuring none would be left behind when the inevitable war reached Beijing.

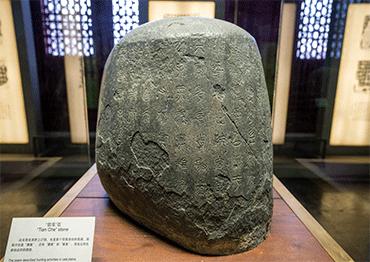

Among these treasures are the Stone Drums of Qin. A set of 10 sculptures, they bear the earliest known Chinese stone inscriptions, carved around the Spring and Autumn (770-476 BCE) and Warring States (475-222 BCE) periods. Another is the San Family Basin (Sanshi Pan), a bronze ritual artifact dating back to the Western Zhou period (around 11th-10th century BCE). The inscription on its circular plate contains one of the earliest Chinese writing systems.

The task was not simple. The staff visited Liulichang, a cultural district in Beijing known for selling crafts, antiques and art, to learn the best methods to pack delicate artifacts.

Back at the museum, each piece was first wrapped in cotton and enveloped in oil paper. It was then placed in a thick wooden crate, filled with cotton and straw to minimize movement during transit. The crate was finally sealed with steel wire. Several trials were conducted, including dropping the crates from certain heights, to ensure they were safe from damage.

While some pieces were left behind due to their sheer size, like the 5.35-ton jade sculpture Yu the Great Controlling the Floods (which is still housed in the Palace Museum), ultimately a total of 13,491 crates were prepared for the largest migration of cultural relics in Chinese history.

There was no time to waste. In early 1933, as China’s defenses crumbled and the frontlines fell, Beijing became increasingly vulnerable. The great migration of cultural relics was about to begin.

Old Version

Old Version