Eleven years ago, Dechen Pelzong, who was a 12-year-old student in the city of Xigaze, suffered from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a condition in which the hip joint in infants is prone to dislocation. It is particularly prevalent at high-altitude locations like Xigaze, though infants do grow out of it and treatments are effective. Treatment is normally done in younger children.

Pelzong felt ashamed of her condition and out of fear of being mocked, she never played with her classmates.

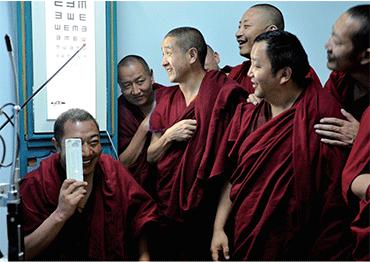

But in 2024 she was full of confidence when the then college student volunteered to serve as a Chinese-Tibetan translator for the Love of Gesang Flower Charity Campaign. Organized by Xigaze People’s Hospital and Shanghai Children’s Hospital, the campaign was established in 2013, aiming to provide free treatment and surgeries to Tibetan children with DDH.

Thanks to Yang Xiaodong, former deputy president of Xigaze Children’s Hospital and founder of the campaign, Pelzong and another 29 Tibetan children underwent free surgery in Shanghai in 2014. Over the next three years, following surgery on her other hip and subsequent physical rehab, her walking gait was corrected.

“She’s the first and oldest child from Xizang to receive the surgery. Her age means the operation is difficult, so I invited Ying Hao, the most prestigious pediatric orthopedic specialist to be the primary surgeon,” Yang, who has also worked for Shanghai Children’s Hospital, told Shanghai media outlet Eastday. com last year.

Yang was part of the seventh team of medical experts from Shanghai to participate in the Xizang healthcare aid program, living in Xigaze from 2013 to 2016. “Before heading to Xizang, we thought the epidemic disease among children on the plateau could have been congenital heart disease, but later we realized DDH was far more prevalent,” Yang told NewsChina in May. As to why the condition is prevalent in the region, Yang and Xigaze People’s Hospital’s orthopedist Feng Xiang suggested in a paper published in 2016 in the Journal of Applied Clinical Pediatrics that Tibetan infants’ legs used to be swaddled in a blanket that restricted their movement, which prevented healthy hip development. There are other risk factors, including altitude, genetics and being female.

Yang said he once visited a county in Xizang and was shocked to find there were nearly 200 children with DDH.

“In Shanghai, DDH shouldn’t be a problem as newborns are screened for it at 42 days old. We rarely see it by the time a child reaches a year old,” Yang told NewsChina.

To reduce DDH in Xizang, Yang submitted a proposal to the Shanghai Health Commission at the end of 2013, asking for the support to launch a screening program, especially for rural children.

“Treating DDH is much easier in infancy than in later childhood, as you only need a plaster cast to correct it. But after around 6 years old, the child might need surgery. If the bone deformity hasn’t been corrected after the age of 8, the surgery is quite difficult,” Yang said.

Since the program started, anesthetists, doctors and nurses from Xigaze People’s Hospital have visited hospitals in Shanghai with Xizang’s young DDH patients, to study treatments and surgical procedures for hip joint correction.

In the latest decade, more than 10,000 Tibetan children have been screened for DDH and 67 groups of patients have received 608 free surgeries funded by the campaign in Shanghai. An interactive prevention and control system for DDH has been established between Shanghai and Xizang to track the progress of young patients, the Shanghai Health Commission released in June 2023.

Yang told NewsChina he could have ignored the DDH cases in Xizang as the disease was not in his remit for the healthcare aid program. But if he gave up without founding the campaign, children with the condition would have always felt marginalized.

Doctors from paired-up provinces and municipalities are also always ready for emergency rescues on the plateau, often working against altitude sickness.

One midnight in 2015, spinal surgeon Zhu Xiaodong at Shanghai’s Changhai Hospital received a call, asking him to take the earliest flight to Xizang to help a man suffering from brain trauma and severe fractures, including to his spine, after a car accident in Xigaze.

Rushing to the hospital, Zhu checked the injured man before conducting surgery in a poorly equipped operating room. After five and a half hours, Zhu was able to save the man, who recovered enough to be able to move himself in a wheelchair. Although his legs were paralyzed, it was a much better result than doctors expected. For Yang, this was the most difficult, thrilling and impeccable emergency surgery he had witnessed in Xizang.

Old Version

Old Version