There are many foreigners who come to China, fall in love with the country and stay for the rest of their lives. However, the ones I know who have managed the green card situation and permanent residency have three out of four things in their favor, namely, a Chinese spouse, money, real estate and fluent Chinese. I have none of those things. Well, I had a Chinese spouse, but I kicked him to the curb soon after the birth of our daughter. I raised her as a divorced person in China in the 90s, painfully scraping together her tuition every term for the local Chinese school from my miniscule salary. We missed out on the opportunity to buy housing when it was still affordable, as I couldn’t afford it. Like most good kids who graduate from a Chinese high school, she won a partial scholarship to a big fancy school in the US and flew away, never to return except for a brief shopping trip here and there. While she is the first to admit she had a wonderful childhood, she doesn’t hold back on the most painful element of her young life. Her big regret is this: her mother is illiterate in Chinese.

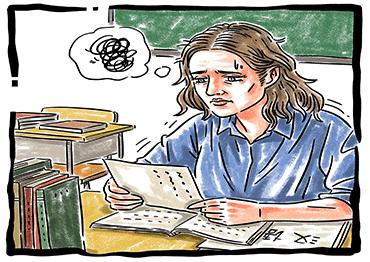

It’s true. I did attend an intense Chinese language program at a university when she was young, but my brain just could not memorize characters. Recognition is an easier skill than recall, so after much effort I could recognize a character, but recalling how to write it? Nope. Not happening. I would sit in exams painfully extracting two strokes, three strokes, while my fellow students were whipping through entire paragraphs. While the ability to read and write in Chinese has been made far, far easier through the use of assistive technology, back in the 90s, if I received a handwritten note from a teacher, I couldn’t simply whip out a cellphone, scan it on WeChat, and then get an accurate translation. But if you were my daughter, you had to find an adult who could read it out loud for you, because you hadn’t learned some of those characters yet. According to my daughter, much of her childhood was spent handing notes to the security guards or taxi drivers we encountered, while she asked in piteous tones, “Uncle (or Aunty), what does this say? My mommy can’t read.”

My inability to learn to read and write in Chinese was painful in the extreme. My background is in education, specifically, the teaching of reading, and here I was, unable to work to anything even close to speed with decoding simple characters. I could speak the language, I just couldn’t write it. During my last exam in the university, as I sat struggling to finish my first sentence in written Chinese, an instructor I didn’t know walked in, grabbed my paper out of my hands, and started laughing and waving it around. I was humiliated. She pointed to some notes I had made in pinyin on the margin (perfectly written pinyin, FYI) and stopped the exam to point out that you cannot learn to speak Chinese unless you can write Chinese characters too. Our conversation was in Chinese so clearly, I could speak Chinese. As she prattled on about how stupid I was, I looked her dead in the eye and said, “So you’re telling me blind people in China can’t speak Chinese because they can’t write the characters?” A collective gasp rose from the room. Her face grew pale and I feared she would slap me. She turned on her heel and walked out. I dropped out that afternoon.

After many years, I started a doctorate in education which focused on the differences in alphabetic and logographic writing systems. I work on curriculums to help Chinese students become more fluent and accurate readers in English. I stumbled onto some methodology that helped me to recognize characters with greater speed, and eventually, to write some without using technology. You’d think my daughter would be proud that I turned adversity into triumph, but no: now that I can read, she’d like me to go back in time and buy some of that cheap real estate. Learn to read in Chinese? Possible. Build a time machine? Not likely, but if got me that coveted permanent residency status, I would definitely be willing to try.

Old Version

Old Version