The excavated Buddhist sculptures include stele carvings, Buddha statues, Bodhisattva statues, Arhat figures and donor portraits. About 200 statues have been reassembled and restored, 90 percent of which date back to the late Northern Wei, the earliest from the year of 529. However, most of the recovered statues are from the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi periods, with a smaller number from the Tang Dynasty. According to archaeological stratigraphy, the burial of the cache is believed to have occurred around or shortly after 1026, but certainly not earlier.

These Buddhist sculptures showcase exceptional craftsmanship, combining techniques such as round carving, basrelief, high relief, openwork carving, line engraving, gilding and painting. The statues are characterized by diverse facial expressions and gestures, exuding elegance and grandeur.

One notable artistic feature is the intricate composition. Many sculptures are set against lotus-petal-shaped back screens, with the central Buddha figure in high relief accompanied by two Bodhisattvas or, in some cases, the Buddha alone. The upper parts of the screens often depict celestial beings flying around pagodas, dragons or jeweled vases, while the lower sections feature coiling dragons with lotus flowers, leaves and buds in their mouths, which serve as bases for the Bodhisattvas. The background often incorporates shallow relief carvings or painted elements like halos, auras and flame motifs. This artistic approach skillfully condenses Buddhist narratives into limited space, evoking a vibrant and harmonious atmosphere.

When observing these Buddhist sculptures, it is evident that those from the Northern Wei period primarily follow the Central Plains style, characterized by solid and imposing features.

However, the distinct Qingzhou style began to emerge during the Eastern Wei. The large, elaborate back screens of the sculptures, featuring graceful curves, celestial beings and pagodas at the top, along with twin dragons coiling and soaring at the base, became a hallmark of this regional artistry.

By the Northern Qi, the characteristic style featuring an elegant skeleton and delicate features was replaced by a new aesthetic. The back-screen reliefs almost disappeared, giving way to standalone, round-sculpted figures. These sculptures often had full rounded faces, symbolizing a shift in aesthetic preferences. Unlike the heavy, layered garments of the Northern Wei, Northern Qi sculptures displayed a completely different physical aesthetic. The clothing was thin and clung to the body, revealing the healthy and graceful curves of the figures.

A particularly remarkable aspect of these Buddhist sculptures is the preservation of their gilded and painted decorations. Previously, it was believed that Buddhist sculptures were plain and uncolored. However, the gilding, which was applied to exposed skin areas of the Buddha, also adorned decorative patterns and ornaments. The use of vibrant pigments was even more extensive. Colors from cinnabar, azurite, ochre and malachite green were applied to clothing, patterns and narrative scenes illustrating the Buddha’s story. The seamless integration of painting and sculpture created a layered and dynamic visual effect, heightening the sanctity and grandeur of the Buddha and Bodhisattva figures.

The sheer number of sculptures unearthed from the Longxing Temple site, their exceptional craftsmanship, the well-preserved gilding and painted details and the extensive chronological span they cover make this discovery unparalleled. It immediately drew international attention and was recognized as one of China’s Top 10 Archaeological Discoveries of the year 1996 by the country’s National Cultural Heritage Administration. It was also ranked 84th among the 100 Major Archaeological Discoveries of the 20th Century by the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2001.

Due to their strong regional characteristics and unique artistic style, these sculptures have been widely recognized by scholars as representing the Qingzhou style and are celebrated for the serene and gentle expressions known as the Qingzhou Smile.

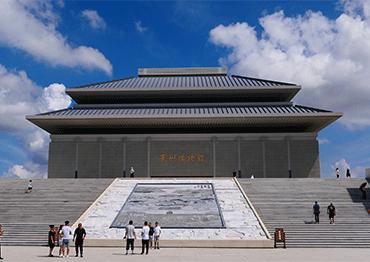

Today, these enigmatic Buddhist sculptures are the crown jewels of Qingzhou Museum. They have been exhibited in major cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, as well as in countries such as the US, Germany, Switzerland, Japan and the UK. Rightly regarded as the “Buddhist statues that have traveled the farthest in the world,” they continue to captivate audiences across the globe.

Research on the collection is ongoing. While scholars generally agree on the dating and stylistic characteristics, there are differing opinions regarding the statues’ origins and the timing of their burial. Some researchers believe that judging from the diversity of styles and inscriptions, the sculptures could not all have originated from Longxing Temple, as a single temple would not typically house such a wide variety of sizes and designs. Instead, the statues are likely to have come from multiple temples across Qingzhou, with Longxing Temple serving as a primary site.

Moreover, it is suggested that the burial of these sculptures was not a one-time event. Instead, it may have been a continuous practice carried out over several periods. This theory is supported by evidence indicating that the statues were interred at different times.

The question of why these Buddhist sculptures were buried underground remains a mystery. Initially, archaeologists speculated the burial might be linked to periods of war or religious persecution, particularly during major campaigns to persecute Buddhists during the 5th to 10th centuries by four Chinese emperors.

In times of turmoil, devout monks, driven by a desire to protect sacred relics, may have secretly buried the damaged statues to shield them from complete destruction.

However, recent archaeological findings provide an alternative interpretation.

Near the Longxing Temple site, researchers unearthed a well-preserved stone stele with a clear inscription. This discovery suggests that during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1126), Longxing Temple frequently held grand Buddhist ceremonies.

As part of these religious observances, monks believed that burying damaged statues from previous dynasties was a meritorious act that could accumulate spiritual virtue and promote the Buddhist faith. Collecting and respectfully burying these damaged sculptures became a symbolic gesture of reverence and devotion.

Thanks to the compassionate efforts of these monks, the enchanting Qingzhou Smiles have endured for over a millennium, allowing us today to appreciate their timeless beauty and serenity.

Old Version

Old Version