The spread of Mazu culture has a long and far-reaching history. Originating in Putian, it gradually expanded along China’s southeastern coast and followed Chinese migrants to communities around the world. Since the Song Dynasty (960-1279), as maritime trade flourished along the ancient Maritime Silk Road, Mazu worship traveled with merchants and sailors. Before setting sail, they prayed to Mazu, seeking her blessing for a safe voyage across treacherous seas. In the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644), famed explorer Zheng He is said to have held grand ceremonies honoring Mazu before each of his seven expeditions (from 1405-1433) to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, rituals that believers say helped him avoid storms and navigate dangerous reefs.

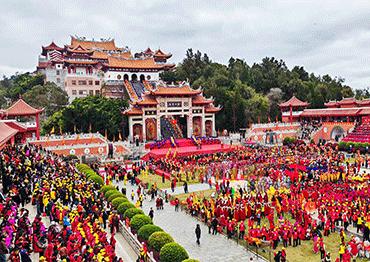

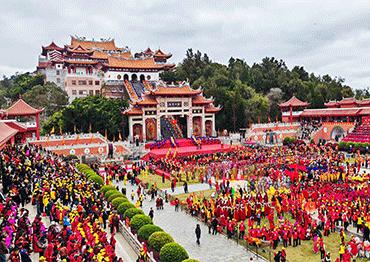

Over time, Mazu worship came to represent more than maritime protection, becoming a powerful cultural symbol and spiritual support for coastal communities. Today, Mazu temples are central gathering places throughout southeastern China. On Mazu’s birthday and ascension day (the ninth day of the ninth lunar month), grand temple fairs draw crowds for folk performances like dragon and lion dances, traditional opera and street processions.

On March 29, 2025, two statues of Mazu departed Xiamen Gaoqi International Airport on a six-day cultural exchange trip to Taiwan. Hundreds of years ago, immigrants from the Chinese mainland brought Mazu worship to Taiwan, where she came to be known as the Sea Goddess. Today, Taiwan is home to over 10 million believers and more than 800 temples are devoted to her.

Li Guoying, an executive with the Chinese Mazu Cultural Exchange Association, told NewsChina that Mazu worship embodies shared values cherished on both sides of the Taiwan Strait and remains a vital thread of national identity. “It demonstrates remarkable cultural appeal and cohesive power, exerting a profound inspirational and guiding influence,” he said. The shared heritage of Mazu fosters mutual understanding and a sense of kinship that transcends political divisions, he added.

Mazu statues are found across Fujian Province in white, gold and pink hues, colors said to reflect her divine aura. But one statue stands apart.

Legend has it that the famed black-faced Mazu of Meizhou Island was originally housed in Chaotian Pavilion inside Mazu Ancestral Temple. During its transfer to the Lugang Mazu Temple in Taiwan by ship, worshippers, worried about the statue being damaged by sea air, placed it inside the ship’s cabin. While on the trip, incense offerings darkened its surface. Far from being seen as damaged, the soot-stained face came to symbolize Mazu’s spiritual power and protective presence. This story contributed to the widespread development of Mazu culture, not just in Taiwan, but around the world.

Mazu is one of the most titled figures in Chinese history, having received 36 honorary titles from emperors over the centuries, including “Heavenly Consort” and “Heavenly Empress.” Her worship spread not only through Fujian and Southeast China but across Southeast Asia, becoming one of the most enduring folk beliefs in the Chinese cultural sphere.

Beyond its spiritual function, Mazu culture serves as a cultural bridge connecting overseas Chinese communities. Temples dedicated to her can be found in Southeast Asia, Japan, South Korea, the US and other countries. In Malaysia, annual Mazu processions attract both believers and tourists. In Singapore, Thian Hock Keng is a prominent Mazu temple that serves both as a place of worship and a symbol of Chinese heritage.

Lin Ziying, chairman of Singapore’s Hin Ann Thain Hiaw Keng, another important Mazu temple, recalled the procession in 2017, when a golden statue from Meizhou toured Singapore. “The streets were packed,” he told NewsChina, “and many elderly Chinese welcomed her with tears in their eyes, holding incense and candles.” The emotional response, he said, captured how Mazu’s presence resonates across generations and borders. “Our pilgrimage to Meizhou is not just about tradition,” he added, “but a heartfelt return to our cultural roots.”

In 2009, UNESCO added Mazuism to its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The designation recognizes the richness of its rituals, legends, folk art and maritime traditions passed down through generations.

Today, Mazu culture serves as an invisible cultural bridge in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, linking China with the rest of the world. It not only promotes economic and trade exchanges but also enhances cultural dialogue and mutual understanding.

Old Version

Old Version