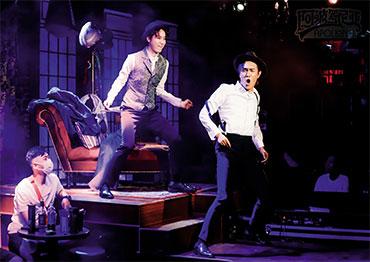

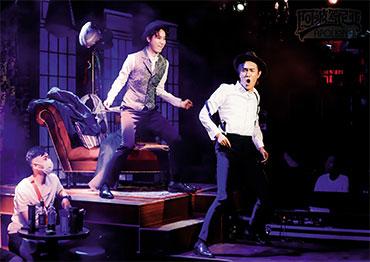

Two days after premiering at Beijing’s Poly Theater, director Zhao Miao’s The Murder in Kairotei, adapted from Japanese author Higashino Keigo’s novel about the family of a tycoon scrambling for his estate, was shut down when the city mandated pandemic restrictions on May 1.

Known for combining Western and Chinese dramatic traditions, the 43-year-old director is an active force in the theatrical community.

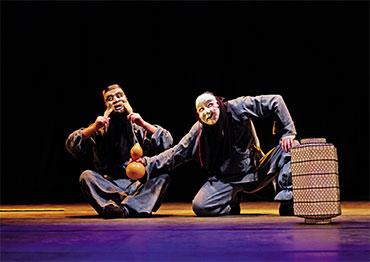

Zhao’s signature small-theater production Aquatic which premiered in 2012, originates from Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) writer Pu Songling’s novel Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, which centers on a friendship between a water spirit and an elderly fisherman. The play features Nuo traditions – an ancient form of Chinese folk opera that involves elaborate masks and folk rituals intended to drive away evil spirits.

While known for larger commercial productions, Zhao’s true love is small theater, where he can take risks, break rules, experiment and make mistakes.

“It feels like diving in deep waters. Sometimes I surface to take a breath, then dive back in again,” Zhao told NewsChina.

As the cradle of the Chinese small-theater movement, Beijing has witnessed four decades of its development. The worn stages of small theaters in Beijing have hosted many avant-garde dramas. Beijing’s small theater has a reputation for being original, trailblazing and highly critical.

In 1982, director Lin Zhaohua staged China’s first small-theater play Absolute Signal in a rehearsal studio at the Beijing People’s Art Theater. The work revolves around a robbery in a train carriage and featured an innovative minimalist set design unprecedented in Chinese theater.

Absolute Signal heralded the Small-Theater Movement in China, which inspired more avant-garde productions. The China Youth Art Theater produced works like The Old B on the Wall (1984) and Social Image (1986). The Central Experimental Theater presented A Visit from the Dead to the Living (1985). Lin Zhaohua directed what became his “trilogy of idlers” – The Wild Man (1985) by Gao Xingjian, and The Chess Man (1995) and The Fish Man (1997) by Guo Shixing.

Director and playwright Meng Jinghui has carried the torch since the 1990s. As China’s most popular experimental theater director, Meng balances art and pop appeal. He directed a series of acclaimed plays including his work I Love XXX (1994) and The Life Comments of Two Dogs (2007) by Liu Xiaoye and Chen Minghao. Meng’s production of Rhinoceros in Love, written by his wife Liao Yimei, which tells of a rhino keeper’s romantic obsession with his neighbor, has been staged over 3,000 times since its premiere in 1999.

Nevertheless, Zhao told NewsChina that Beijing’s small-theater movement has lost ground since 2019. As the market contracted, creatives moved south to Shanghai for new opportunities.

Beijing’s small-theater boom came in the 2010s, with venues like the North Theater of the Central Academy of Drama, The Little Theater of Beijing People’s Art Theater and the Avant-Garde Theater of the National Theater Company of China taking the lead.

However, the number of small theaters has since dwindled. Only a few, such as the Drum Tower West Theater and Penghao Theater remain, struggling to keep their doors open.

Rising rents are partially to blame. In the mid-2000s, Zhao said small theaters paid about 2,000 yuan (US$300) per show. But over the past five years, that has increased to 10,000 yuan (US$1,500).

Another reason is a shift in audience tastes. Younger audiences prefer light-hearted commercial shows over serious theater. “For many, life and work are already somber enough. Do they really want to unwind after work with a serious show?” Zhao said.

Li Yangduo, founder of the Drum Tower West Theater said that all a good play takes is a space, imagination and creativity. “But the sad fact is that Beijing has lost more and more theaters and talent over the past two years,” Li told NewsChina.

“But if Beijing’s small-theater movement no longer takes on serious issues, no longer explores the world and the individual, then it would lose its meaning,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version