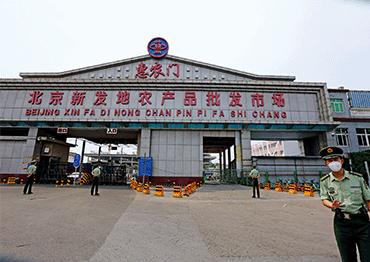

What started in 1988 by 15 rural workers from Xinfadi Village, the market now covers 112 hectares and has 18 gates, its labyrinthine corridors earning it the name “The Big Maze” among locals. Although the market complex has seen renovations since 2010, such as paved roads and additional buildings, until recently Xinfadi still operated the same way it has for decades - bustling with buyers, sellers and trucks starting at 1 am daily.

According to a Beijing News report, Xinfadi had over 5,500 produce stalls selling vegetables, fruits, seafood, pork, beef and mutton to over 8,000 regular customers from around the country. In 2019, Xinfadi saw 17.5 million tons of produce, ranking it first in trade volume among the more than 4,600 agricultural wholesale markets nationwide for 17 years straight. Around 60,000 people and 30,000 trucks visited the market every day.

“Xinfadi’s products are traded on-site and in cash, so people deliver and pick up produce with trucks. This basic trade means frequent contact between people,” Dai said.

According to Dai, auctions are better for wholesale markets. While visiting a market in Japan in the 1990s, Dai witnessed that auctions did away with on-site loading and unloading, making the process more orderly and efficient. There are only a few dozen certified wholesalers in each market. Transactions were transparent and conducted quickly.

Yet, Dai said the Chinese mainland is unprepared to conduct produce auctions. “A fundamental part of auctions is uniform production, but agriculture in China is scattered and covers a wide range... Chinese farmers, for example, could not supply only one or two varieties of tomatoes in unified packaging like farmers in Japan and South Korea do,” he explained.

Shenzhen was the first city on the mainland to hold wholesale auctions at a local market in 1997, but trade volume remained low, and the market suffered. Cities like Shouguang in Shandong Province, Guangzhou in Guangdong Province, Dounan in Yunnan Province, and Beijing also held auctions at their flower markets with minor success.

To boost efficiency, most wholesale centers on the mainland had adopted spot market trading by 2010. However, it failed to catch on. Experts blamed China’s low intensive agricultural production. According to data from Xinfadi, electronic trading made up only 9 percent of total sales volume in 2014.

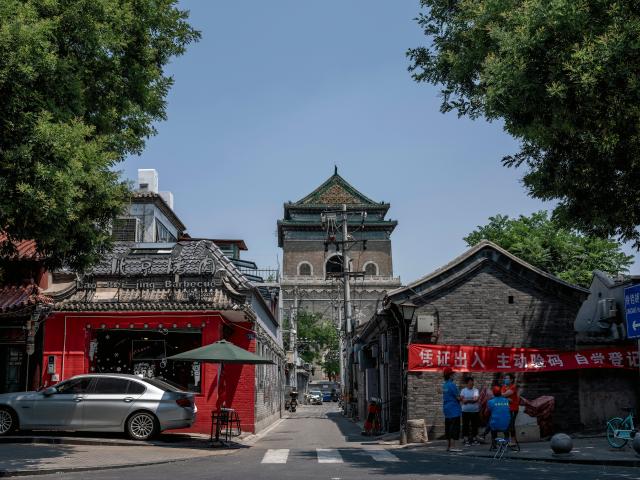

Most wholesale markets also deal in retail, which significantly increases traffic. Though Asia’s largest wholesale market, Xinfadi was the primary source of produce for average Beijingers, many of who were local elderly residents doing their daily shopping.

Official data showed that in the latest wave of coronavirus, many of the confirmed cases, including the first one, had grocery shopped at the Xinfadi market.

“I noticed that wholesale markets did not differ from retail wet markets. I don’t think big crowds are what wholesale markets should pursue. Actually, it’s a sign of low efficiency... We have to separate retail from wholesale as soon as possible to reduce traffic flow and increase truck rotation,” An Yufa, a professor at China Agricultural University, said in a report published on the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection website on June 17.

“As people have increasingly higher expectations for living standards and environment, we cannot allow wholesale markets to remain the same as they were 20-30 years ago,” he added.

Old Version

Old Version