Despite two decades of efforts, most urban and rural recycling projects have failed. Now some community-led attempts to clean up their environment are proving successful. Can they be rolled out on a wider scale?

Three years ago, Xinzhuang Village in a rural area in northern Beijing was a much smellier and dirtier place. Most household waste was disposed of in open dumpsites, a common practice in rural China. “Garbage collection spots were smelly and overflowing, and attracted mosquitoes and other insects,” said resident Tang Yingying. But since early 2016, the village of 400 households and some 2,000 residents decided to tackle the situation themselves, in the absence of any top-down measures targeted at rural areas.

Households now separate their waste into four categories – kitchen waste, general (or non-recyclable) waste, recyclables, and hazardous waste. Every morning, Tang told NewsChina, a sanitation worker, riding a tricycle which plays musical chimes, pedals around the village to pick up sorted garbage right from the doorstep of each home.

Ripple Effect

In April 2016, bothered by the odor and traffic congestion caused by 17 dumpsites scattered all over Xinzhuang and in order to make a better living environment, Tang and a few other villagers persuaded village leader Li Zhishui to institute a village-wide garbage sorting program.

Li was receptive, as he was already under pressure to find a solution to the problem of the spreading trash dumps, which were encroaching on village land. After clearing and removing all community dumpsites within the village domain, each household was allotted four trash bins. The village introduced a door-to-door collection program through which households must personally hand their waste to village sanitation workers every day.

“When the garbage truck from [nearby] Xingshou Township Sanitation Center comes to Xinzhuang, the collected and sorted garbage is transferred to the truck in one go, and transported to Asuwei Garbage Disposal Facility for further treatment,” said Gao Shuaijie, director of Xingshou Town Sanitation Center. Asuwei is one of Beijing’s major garbage treatment centers, 20 kilometers from Xinzhuang.

The village generates an average of 1.2 tons of waste a day, and in 2018, reported a recycling rate of 80 to 90 percent, extremely high by any standard. According to a research paper published in March 2018 by Zhou Chuanbin from the Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the estimated average national waste recycling rate in 2015 ranged from 11.2 to 20.6 percent. The goal for cities which will introduce garbage sorting by 2020 is a recycling rate of up to 35 percent, so the small-scale project in the village is achieving great results.

Villagers saw an immediate improvement to their environment, and this initial success soon drew support from the local township government in Xingshou. Since 2017, the township started extending the scheme to other areas under its jurisdiction.

“So far, 16 villages we administer practice trash sorting. Kitchen and non-recyclable waste is collected every day, and households can sell recyclables directly to recycling companies,” Gao said. “But because there are no organizations able to collect and handle hazardous waste, we have to collect it regularly from villagers and temporarily store this waste at our center.” This includes items like batteries and spent fluorescent tubes. According to Gao, Xingshou aims to have garbage sorting systems in all 20 villages in its jurisdiction by the end of 2019.

After getting residents used to separating their trash, the next step for Xingshou is to reduce the amount of waste thrown away. This includes encouraging the composting of kitchen waste like fruit or vegetable peelings. Starting in June, household wet waste is transported to compost units in town, where it is mixed with local agricultural residue from strawberry farming to be used in other horticultural or strawberry planting projects. Xingshou town processes about three tons of wet waste daily. With proper and sustainable treatment for kitchen waste, the town expects to reduce its annual 25,000 tons of garbage by 25 percent in 2020.

Tang said in the long term, it would be ideal to reduce kitchen waste to make use of the compost for organic farming inside Xingshuo. “I feel it’s easier to sort trash in rural areas, because it’s mostly kitchen waste, and it can be used directly as organic fertilizer for farming,” Tang said. “But what’s really crucial is for local officials to get behind these efforts to sort trash in both rural and urban area in China.”

Piling Up

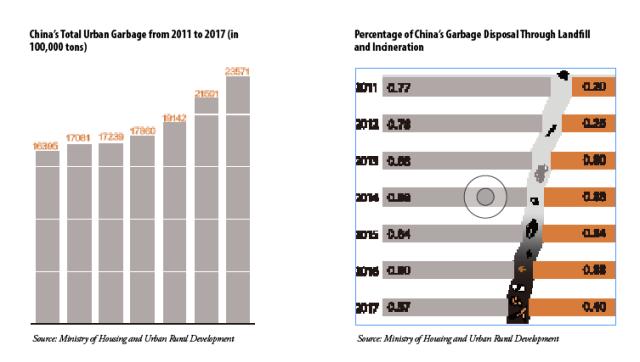

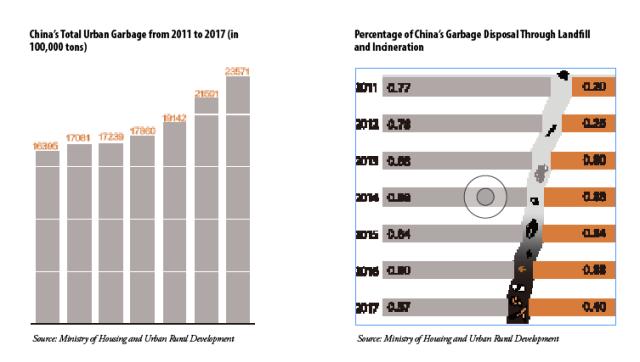

In 2000, total national household garbage in China was 11,818 million tons, according to statistics from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development. But a report released by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2018 showed that the amount had more than doubled. In mega cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, annual household garbage exceeded nine million tons. Without proper sorting, landfills and incineration of mixed garbage have caused soil and water pollution, along with concerns over the health of nearby residents.

Since Shanghai became the first major city in the Chinese mainland to enforce a system of trash sorting and recycling, the national campaign to deal with garbage has gained new momentum. In early June, nine ministerial level departments, including the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, released a decision on launching household garbage sorting classification in all prefecture-level cities within the country in 2019 and on setting up treatment systems in all prefecture-level cities by 2025. Beijing vowed legislation on garbage sorting by 2020.

Attempts to promote garbage classification in China started in the late 1990s when cities started to struggle with the fast-growing piles of waste. Official data shows that from 1978 to 1991, urban garbage in China increased by 10 percent year-on-year. Government and environmental experts have agreed that reducing garbage at source was an important step for garbage treatment. According to the Urban Household Garbage Management Guideline released in 1993 and the Prevention and Control of Solid Waste Pollution Law released in 1996, garbage sorting and collection are obligatory.

In 2000, eight cities including Shanghai and Beijing were appointed by the central government to start pilot programs on garbage sorting. Some progress has been made. According to Sun Xinjun, director of the Beijing Municipal Commission of Urban Management, to date, over 100 registered communities have started sorting domestic garbage, accounting for 30 percent of the total registered neighborhoods in Beijing, and by 2020 the figure is expected to rise to 90 percent. However, awareness and implementation varies from region to region, or even community to community. For example, in a local residential complex and its surrounding area in Shunyi District, a mixed rural and relatively upscale suburb of northeast Beijing, there is no garbage sorting at all. Most communities still pay lip service to trash sorting, so even if recycling bins or those for food waste are available, no one pays any attention. They know that the garbage collectors simply put it all in the same bin anyway.

According to Mao Da, a scholar in environmental history and an advocate for the environmental NGO Zero Waste Alliance, efforts to properly deal with household waste have experienced ups and downs. Apart from failure to cultivate long-term habits among residents and maintain waste separation after collection, one key debate between supporters and opponents for garbage sorting is over the additional extra financial cost.

“Incinerating and putting unsorted garbage in landfill is much easier for public affairs management, and some even claim that the cost of sorting and transferring low-value recyclables is much higher than mixed garbage treatment, thus resulting in social inertia and refusal to promote it,” Mao said. “But it’s true that studies have proved garbage incineration costs have been underestimated.” Research led by Professor Song Guojun of the Renmin University of China’s School of the Environment and Natural Resources released in late 2017 indicated that the cost of the process of “collection-transfer-incineration” of municipal solid waste management was 4.22 billion yuan (US$613m), equivalent to 2,253 yuan (US$327) per ton, way higher than the 40-300 yuan (US$5.8-43.6) per ton for garbage disposal charged by the municipal government. The conclusion of the research was that “the cost of municipal solid waste incineration was huge, but most of it was concealed,” and furthermore, taking health risk evaluation of the hazardous air pollutants into account, it would even make the cost of the waste incineration soar “out of control.”

Mao told NewsChina that interest groups that depend on government subsidies for incineration projects are not bothered about sorting garbage. Xue Tao, executive head of the E20 Institute, an environmental think tank, also told the 21st Century Business Herald that for incineration enterprises, a reduction in the amount of waste is not to their benefit. It is clear garbage treatment processes remain a major stumbling block, which will not be solved just by improving household recycling rates.

“We need continued top-level dedication to force change,” Mao said. Song told the Legal Daily in an earlier interview that “legal compulsory garbage classification at the source, be it a household or office building,” is necessary, and that “people who do not comply should be punished.”

Material Returns

According to industry insiders, the recent strong political backing from central authorities provides more opportunities for private sector involvement at all stages of the garbage collection and treatment cycle.

“Many investors are attracted by the fast development of the industry and the strong government support,” said Xu Yuanhong, founder and CEO of Ai Fenlei Science and Technology Co. Ltd., a social enterprise working in Beijing to solve recycling issues. “But they lack understanding of the garbage industry.”

Xu, a college graduate who first started a recycling business in 2004, set up Ai Fenlei (Love to Sort) in 2017 aiming to facilitate community garbage sorting and recycling. Xu said that under his company’s scheme, people only need to separate wet and dry waste. They simply call or use a mobile app and Ai Fenlei staff comes to their home to collect the garbage. The company offers material rewards through a points-based system to encourage the community to remain committed to garbage sorting. Ai Fenlei staff sorts the dry waste into 50 categories, packing it separately and transferring it to companies which process the different types of waste material. Due to the transparency of the company’s sorting procedure and the strict rules it abides by, communities have a lot of trust in Ai Fenlei.

Through government procurement, Ai Fenlei has signed contracts with a number of communities in Beijing. “Changping District is supportive and our enterprise has gained financial subsidies of over three million yuan (US$436,071) for the whole process of garbage sorting in three towns within the district,” Xu said.

“If we want to promote the separation of wet and dry waste in more parts of the city, we’ll need more support from Beijing municipal government. But we’re confident about the future for the garbage sorting industry and we expect things will really start to take off soon.”

But there are few companies like Ai Fenlei in China. Shanghai, the city pioneering this recent new round of garbage sorting implementation, has made plans to provide support and franchising rights to enterprises which can reprocess low-value recyclables. According to a 21st Century Business Herald report, Soochow Securities, a cooperative that offers investment consultation services, projected a potential 380 billion yuan (US$55.3b) investment market for kitchen waste management in the future.

Professor Du Huanzheng, director of the Research Institute of the Recycled Economy at Tongji University in Shanghai, has proposed a whole set of strategies to tackle urban garbage. He said that waste sorting, transportation and end treatment require systematic coordination, and called for a long-term effective mechanism which incorporates stakeholders including government, enterprises and the general public, as well as non-governmental organizations. Du pointed out that garbage sorting is necessary for the circular economy, which refers to a more or less closed system in which resources are used for as long as possible, and as much material as possible is recovered at the end of a product’s life. China has had goals regarding the need to promote a circular economy since 2002, and it is included in central economic planning regulations.

“The end treatment of low-value recyclables requires investment from enterprises and the government,” Du said. “It is necessary for the government to provide franchising rights, land purchasing subsidies, low-value waste reduction subsidies and green purchasing systems to enterprises so more private firms will be attracted to the garbage end treatment industry.”

But end treatment will only be successful if waste producers are committed to sorting and reducing trash. Tang Yingying thinks it is important to tell people where their garbage ends up. She thinks that if her fellow residents of Xinzhuang understand how the whole process of waste treatment works, they will continue to be enthusiastic about recycling and waste sorting.

“The public needs to know their waste sorting is useful,” Tang said. She told NewsChina that some enterprises have expressed willingness to cooperate with Xingshou township government in recycling sorted end garbage, but for the moment it requires sustained financial support from the local government so they are not working at a loss.

“Fostering an independent profitable market for recycling garbage requires a significant quantity [of trash], and this takes time. We hope the local government will make favorable policies to support the private sector for the treatment of sorted recyclables,” Tang said.

“But before we set up any overall social structure for garbage sorting and separate end-treatment, we as individuals can be responsible for our own behavior, and we should stick to the habit of sorting garbage first for our own sake,” she said.

Old Version

Old Version