Living on a shoestring can be fun, so long as you have the right guide.

I am not new to China; it’s my childhood home. When I lived in Shanghai I even attended a local Chinese high school. I thought I knew what it was like to be immersed in Chinese culture. I was wrong.

Last year I moved away from home for the first time. I moved to Beijing, happy to get away from the drab little Swedish town where I’d finished high school, excited to be living alone in a big city. I was moving in with a friend’s friend, Jing, and we’d be rooming together for two weeks. She was going to help settle me in.

When I arrived hot and sticky from my trip across the world, it slowly dawned on me that this time my life in China would be different. When attending a local Chinese high school I would spend my days as a Chinese kid but go home to a Western family. This time around it wouldn’t be like that. Jing was about to teach me how to live like her 24/7 – how to live like a Chinese 20-year-old on a tight budget.

It was a lot of fun. Not the least because Jing is one of the most outspoken, intelligent, open-minded people I know. But also because, though we bonded on so many levels, sometimes her old country-bumpkin ways (she grew up in a tiny Shandong village) would shine through, which I found fascinating. Memories come to mind of us discussing politics with her happily suckling on a pig’s trotter.

When I first got to Beijing she was quick to teach me everything she knew. The first thing she prioritized over all else was giving me slippers to wear at all times indoors; a Chinese custom. At first, I left them all over the apartment. My first days in Beijing were spent searching for them under chairs, tables and sofas. Jing didn’t understand why I was having such an issue keeping track of them and when I explained that in Sweden we walk around barefoot she dismissed the idea as impossible. Today I’ve gotten so use to it that I feel naked without them.

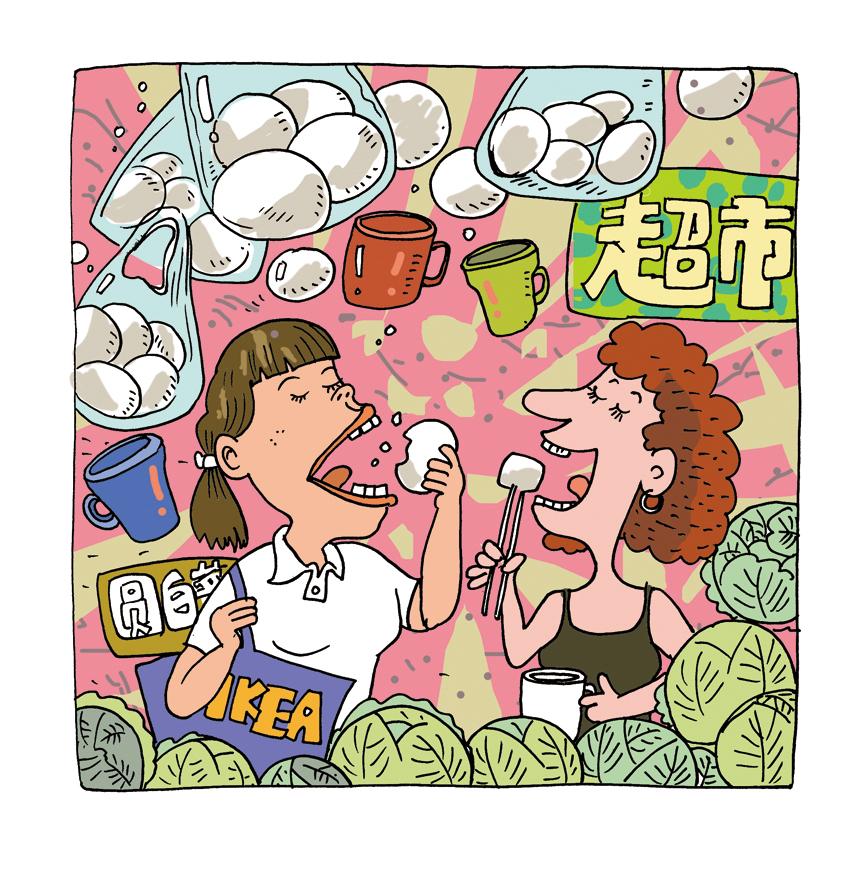

My next lesson was how to shop in IKEA. I wasn’t thrilled to be visiting the Swedish store, especially since I’d traveled so far to get away from that country, but Jing’s way of shopping in IKEA was special. She grabbed me by the arm and we flew through the shop to find mugs and bowls. “This one’s the cheapest,” she would say, pointing at a three-yuan (US$0.46) mug, then she’d pause – “Oh no, wait! This one!” – and we’d fling ourselves over a hamper of mugs marked half a yuan lower. I suggested buying cutlery, but she just shook her head. “Cutlery is cheaper on Taobao,” she explained. “The mugs and bowls are cheaper here. We’ll get those.”

When we walked past a box full of frying pans, I shuffled over to them sheepishly, remembering that our apartment only had woks. I pointed at the frying pan and asked if we should get one. Jing laughed, “What would you use it for? Frying eggs?” I realized I was asking for all the wrong things, so I just let her decide what to buy.

After IKEA, the next lesson I learned was how to cook. Jing taught me how to make a dish of potatoes and green beans. From then on, every time she made congee or stir-fried tomato and eggs I would watch and take notes. At first the thought of a wok terrified me. I desperately called home, asking my mother how to fry eggs in a wok. Today I don’t really know what I’d do if the pan was flat.

The cheap, white bun mantou, I also learned quickly from Jing, is the poor 20-year-old’s best friend. Jing and I would go to the supermarket once a week to pick up freshly steamed mantou, three yuan for five. Cabbage is also a godsend. Jing taught me how to cut up a cabbage into strips and mix it with vinegar, soy sauce and salt. That, together with a mantou, makes a surprisingly filling meal under for well under a US dollar.

Jing took me to the vegetable market near our house several times during my first few days. It always took a while because she’d be getting into fights with the salespeople that were swindling us of three or four cents. One of the salespeople laughed and insisted it was fine to trick a foreigner. “She understands Chinese you know,” my roommate spat in my defense, “and you can’t trick her just because she’s foreign. Her Chinese is better than yours.”

My roommate has since moved out to a dorm at her university in Haidian District. When she comes back and sees me eating my cabbage and mantou she says she’s proud of how well I am doing alone.

I have to admit there are some things I have changed since she moved out. I couldn’t live in a room with the white fluorescent lights. Also, you can never completely kill my inner-Swede, so yes, I bought the expensive candles from IKEA.

But some things have stuck. Living with Jing made me realized that for some people, water and food is a precious thing. You’ve got to make the most of what you’ve got… and mantou is also just really darn good.

Old Version

Old Version