Old Version

Old Version

Higher Education

For graduates of Lanzhou University, history provides a saddening reminder of how fast a star can fall.

In the early 1950s, when the newly founded People’s Republic of China was borrowing from the development experiences of the former Soviet Union, Lanzhou, capital of northwest China’s Gansu Province, lying at the very heart of the Chinese territory, was made a major base for heavy industry and enjoyed all manner of preferential policies. And so did Lanzhou University (LZU).

In 1954, LZU became one of the 14 universities to attain the prestigious status of being directly managed by the Ministry of Education. In 1960, it was already one of a shortlist of government-approved “national key universities” and the only one in northwest China.

Back then, Lanzhou was a promising industrial town, where seven out of the 156 Soviet Union-aided projects across China were located. It was particularly well-known for its chemical industries, which had also earned LZU’s chemistry department considerable support from the central government. Many Chinese scholars who returned from studying overseas at the time were assigned by the central government to work at LZU.

Lecturers and research students were also transferred by the central government from Peking, Fudan and Nanjing Universities to fuel LZU’s chemistry research, which is partly why the university remains one of the country’s top institutes for chemistry to this day. Its rapid growth in the 1980s made LZU one of the top 10 Chinese universities in terms of the number of graduates being elected as academicians at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the country’s top research body.

But a policy change in 1986 later proved fatal to LZU’s prospects in subsequent years.

The government used to fund universities based on the number of teachers they had, Wang Cheng, current president of LZU, told NewsChina. When China operated with a planned economy, Soviet style, Wang said, the country’s less-developed western regions enjoyed the special support of national policies. In the first few decades of the People’s Republic, college teachers in west China were paid a third more than their peers in the richer coastal provinces, he said. The policy remained in effect until 1986, the year that saw the beginning of a decades-long brain drain for LZU.

The decline began when the university’s academic heavyweights who, after spending a lifetime at LZU at the behest of the government, left to work in universities in their eastern hometowns, taking with them academic resources. Others left for better pay, greater career potential and better education prospects for their children.

According to Li Yong, a renowned writer and LZU alumnus, in the 1990s LZU became one of the main targets for headhunting by the emerging universities in China’s richer provinces. When Qingdao University, in east China’s Shandong Province, launched its Chinese department, it was almost entirely staffed with personnel they had poached from LZU, Li told NewsChina. In May 1998, an elite university plan proposed by then president Jiang Zemin, known as “Project 985” was launched, aimed at improving the standards and reputations of Chinese universities.

Ultimately, a selection of 39 universities across the country was finalized. These institutions would be funded jointly by central and regional governments, causing the funding gap between universities to widen. Lanzhou University was not one of Project 985’s first round of universities that received special funding.

In 1984 and 1985 alone, 255 teachers left LZU for universities and institutions on the east coast, according to LZU’s records. Between 1991 and 1994, there came another major outflow of more than 200 teachers, while between 2000 and 2004, the university saw 40 associate professors leave, many of whom were recognized as the country’s leading researchers in their fields.

This severe brain drain was immediately followed by LZU’s falling rankings across various different academic indicators and consequently its reduced attractiveness to high school graduates. In terms of admission score requirements for the College Entrance Examination, the main and in most cases only criterion for college admission in China, LZU currently ranks 76th, meaning it is seen as relatively easy to get a place there, a status that obviously does no justice to its academic reputation.

“Who doesn’t want to go to better places?” said LZU’s president Wang Cheng to NewsChina. “Without the particular support of national policies, nobody would ever want to come [to LZU].”

Though they’ve been working hard to improve their staff management mechanisms, weak support in terms of regional financing and the growing competition among Chinese universities for researchers have made the brain drain an ongoing and delicate problem here at LZU, said Wang.

Li Yong believes the fundamental principle of education is equal opportunity, which includes the reasonable allocation of educational resources among different regions. The regional gap as reflected between universities emerged in the late 1980s, by which point China’s economic takeoff had allowed the east coast to soon take the financial lead.

Previously, the regional economy had only the faintest bearing on the key universities as they were entirely funded by the central government.

After major reforms in 2000, most institutions started to be managed by local governments, except for a small number of universities that remained under the direct management by the Ministry of Education. Universities selected by Project 985, all of which are ministry-managed, are funded jointly by the central and regional governments. Both situations allow universities in the richer parts of the country to become increasingly financially independent and resourceful and thus can easily lure talent from their counterparts in less-developed provinces.

Before the 1990s, despite the central government’s designation of a number of universities as key universities, the hierarchy of institutions was never as strict as it is today. According to a study on the allocation of China’s higher educational resources, published in 2008 and funded by the Ministry of Education, during the 1950s, Chinese universities underwent a major reshuffle that allowed any regional gaps to shrink to a historic low.

Today, however, the majority of China’s best universities, including some of the Project 985 participants, are located in east China. Those that lack this geographic advantage are gradually losing their human resources and academic reputation to their counterparts in the richer areas that are simply able to pay more for faster growth.

“The gap between universities hasn’t narrowed after all these years. Instead, there’s now a ‘Matthew effect’ that allows the strong ones to grow stronger and weak to become weaker,” said Li, referring to the sociological concept of one party becoming increasingly privileged when others do not. The example given by the concept’s creator, Robert K. Merton, was that an eminent scientist will gain more credit than a relatively less well known one for comparable research.

The reform has left the development of a university to be largely defined by the local economy in which it sits. Xi’an Jiaotong University (XJTU), located in northwest China’s Shaanxi province, is generally considered to be the legitimate heir of Chiao Tung University (CTU), known as China’s MIT in the 1930s. It has been outshone by its sister university Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU), which developed from a very small part of CTU left behind in Shanghai after it was relocated to Xi’an.

While Shanghai’s economic strength has allowed SJTU to grow in the past two decades into one of the country’s top five research institutions, XJTU with a budget only half that of its Shanghai sister had to lose nearly 600 leading researchers and teachers between 1996 and 2000.

Statistics have shown that northwest China’s Gansu Province has seen over a thousand senior scientific and technician personnel, half of them from research institutions such as Lanzhou University, leave for universities in eastern provinces. In China’s northeast, the country’s former industrial base currently in an economic downturn as it struggles to adapt to a post-industrial present, universities face an equally severe brain drain.

“Taking Jilin University [in China’s northeastern Jilin Province] as an example, the number of personnel that have left the university is practically enough for building a new ‘Project 211’ university,” said Li Yuanyuan, president of Jilin University. Project 211, implemented before Project 985, is a wider scheme introduced by the central government in 1995 that aimed to help about 100 universities to develop.

According to the 2008 study of educational resource allocation as mentioned above, in 2004, universities in east China had 390,000 full-time teaching staff, while the number was only 175,000 in west China. Five provinces in east China, including Jiangsu and Guangdong, reported over 3,000 full-time teachers each, while no western provinces had reached that number. Population differences do not explain the extent of the gulf.

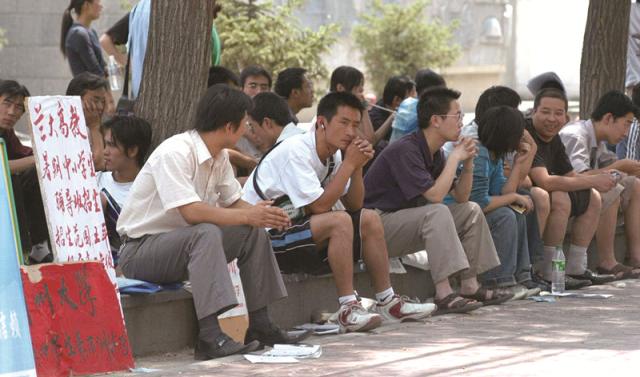

Students offer tutoring services outside Lanzhou University

While it may appear that the widening regional gap between Chinese universities is the work of the market forces unleashed by China’s endeavors of reform and opening-up, it reveals the weak role of the market when the government still acts as the leading force in allocating China’s educational resources.

The gap between Chinese universities is fundamentally a regional economic discrepancy, as the reform allowed regional governments to also take a part in the development of universities, said Xiong Bingqi, vice chairman of the 21st Century Education Research Institute. The unbalanced flow of college personnel is thus not the result of an open educational market, said writer Li Yong.

The bureaucratization of university management has divided China’s universities virtually into different classes. Chen Houfeng, a researcher at Hunan University who participated in the study on the allocation of China’s higher education resources, wrote in an article that while China has a fixed education budget, top-ranking universities are getting an excessive share of it. They have sucked up the money that could otherwise have been spent on lower-ranking universities and vocational schools, Chen wrote.

Moreover, top-ranking universities also tend to be more resourceful in private fundraising, Chen said, adding that the result is a continuously-widening gap between the rich and the poor. The unequal distribution of educational investment has directly led to unequal opportunities for development of higher education, said Chen.