It was the early hours of Thursday morning when Shi Yan, a 32-year-old office worker, took a flight from Beijing to her hometown in coastal Shandong Province to buy an apartment. She had just come back from another business trip at midnight, only to get straight on the plane so as to avoid any chance of missing out on the deal. When she finally got all the documentation and signed the purchase contract on noon Saturday, she was too rushed to even calculate the price per square meter. But she was happy with the deal, stunned by the crowd at the sales office and jubilant when she learned an apartment nearby was offered just 25 days later for a price 15 percent higher per square meter.

Buyers are not the only ones in a rush. As China’s real estate boom continues, developers are hurrying to snap up any chance possible. On September 20, a day after housing purchase restrictions took effect in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, land use rights for housing developments were hitting record levels at auction, reaching over 300 percent above the starting bid within a few hours. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the first eight months of 2016 saw Chinese developers competing for 8.5 percent less land at 8 percent higher prices than the same period in 2015, with “land kings” breaking successive national and local records. While Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen, China’s mega-cities, were already in the grips of a housing fever, by the start of 2016 it had spread to prosperous second-tier cities, including provincial capitals and economic hubs.

This wild exuberance has raised wide concerns about whether this is the final frenzy of a bubble about to burst. Is China heading toward a bust that could mean a financial failure similar to the US subprime crisis, followed by Japanese-style stagnation and a “lost decade?”

In both cases, the real economy, the strongest shield against any shocks anywhere in the world, was hurt the hardest. In China, even though an asset bust does not look imminent or unavoidable at present, the damage to the real economy is already visible. Worse still, the rush to assets has come at a time when the country, on average, is still much poorer than the US and Japan were at their peaks.

Shallow Pockets

Reducing excessive real estate inventory, particularly the massive unsold floor space outside mega-cities, was set by the Party as one of the five major reform tasks of 2016. Restrictions on housing purchases imposed on households in 2010 and 2011 to curb the previous fever had already been eased or annulled by some local governments after the second half of 2014 to address the economic slowdown, partly due to the decline in housing sales. In this context, the clear signal from the top to revive the housing market immediately triggered a spree in mega-cities, despite much tighter restrictions there than in smaller urban centers.

On its own, the spread of housing fever to second-tier cities matched the demands of the policy to clear unsold space. It would have been applauded, but the fever has gripped the market so fast and so forcefully that it’s challenging the idea that Chinese households’ financial position is strong enough to bear more debt. Policymakers have been looking for households to contribute more to economic growth, given the heavy indebtedness of China’s enterprises and local governments.

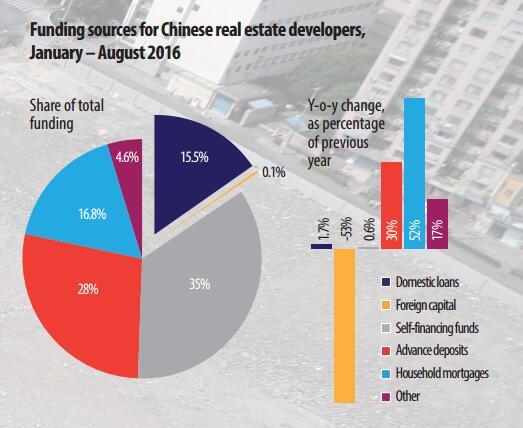

But economists are pointing to some signs of danger. In July, the value of mid-and-long term household loans, the majority of which are mortgages, was 102 percent of the value of increased outstanding loans from June, with reductions in short-term household loans and corporate loans. New mortgages for the first eight months of 2016 made up more than 7 percent of total GDP in this period, very close to the 8 percent peak before the subprime mortgage crisis in the US. And the value of mortgages now totals 30 percent of China’s current annual GDP, nearing the peak during Japan’s housing bubble.

These figures are alarming enough. But Jiang Chao, the chief economist of Haitong Securities, thinks the real picture could be even more dramatic. In a recent widely republished analysis, he argued that estimates were leaving out a unique source of financing for Chinese buyers. Under Chinese regulations, a certain percentage of salaries goes to a national housing fund, providing a scheme that allows relatively low-rate mortgages.

Taking this into account, Jiang thinks mortgage payment accounted for six to seven percent of the average post-tax and social security payments income of all urban households, including those who lack mortgages. This was well above the current figure in the US and approached the seven to eight percent peak in the US before the crisis.

Tan Xiaofen, an associate professor at the Central University of Finance and Economics, has been tracking China’s debt data for a long time. At a September forum sponsored by the National School of Development of Peking University (NSD), he told NewsChina that as the real estate is the biggest source of wealth for Chinese households, a property bust would be a big blow to the financial security of Chinese families.

Systematic Risk, Weak Defenses But Tan argued that China has lines of defense to ward against a US-style crisis. He told NewsChina that two key ingredients of the US subprime crisis are almost entirely absent in China. The first was the prevalence of zero-down-payment mortgages, and the other is complicated mortgage-backed financial derivatives that spread the risk across the entire economy and conceal bad loans among good ones.

The Chinese government, at both central and local levels, has often raised down payment requirements to curb housing fever. And developers are prohibited from using the stock market to finance the purchase of land or make their interest payments. But these risks are still present. Some agencies have found ways around the rules, offering loans to under-financed buyers. On October 21, the China Banking Regulatory Commission listed financing irregularities in the housing sector as a major systematic risk in the fourth quarter of the year. An investigation by Xinhua News Agency in August found that developers were playing a cat-and-mouse game with regulatory watch dogs by shifting to the bond market and shadow banking, in which commercial banks are big investors. There are strong concerns over the concentration of risk in banking, which dominates China’s financial sector. If things go wrong there, the consequences could be even more cataclysmic than in the US.

Tan identified another risk; the lifting of an existing ban on companies purchasing residential property. He was worried that this could add fuel to the flames, as companies are much bigger players than households.

Buyers and developers aren’t stupid. They know the music will stop at some point as the crazy rhythm is out of time with the macro-economic situation. As nearly every analyst has pointed out, buyers and developers are pouring their money into housing exactly because they are seriously worried about the country’s growth prospects and the devaluation of their wealth. Plus there’s little else on offer. Investors have lost faith in the stock market since the crash in June 2015, despite the best efforts of the government to prop it up. Banks’ wealth management products, which enjoyed a spate of popularity a few years ago, have lost appeal after an increased money supply dragged returns down. Private online lending platforms are struggling with frauds and Ponzi schemes.

But most of all, these players believe the government will never let the housing sector go bust. The government is not only critically conscious of the weight of the real estate sector, but is also heavily reliant itself on land transfer fees and housing-related taxes.

Corrosive Effects

An old debate has resurfaced; is the housing sector holding the wider economy hostage? The question makes sense because the housing frenzy is doing plenty of damage. Financial crises are triggered by asset busts, but behind that is a sudden crisis of confidence among investors who find the real economy cannot support the inflated asset prices. The housing boom is distorting China’s economic structure and weakening its dynamism, and could result in a weaker real economy that may not be able to bear the weight of an exaggerated real estate sector.

More money for housing means less spent elsewhere. Retail sales of consumer products in China have continued to rise since 2008, contrasting with volatile investments and declining exports, but the rate of growth has slowed. Research by Zhao Qing at the Suning Finance Institute, published on caixin.com on September 27, attributed the slowdown to the growing burden of mortgage payments.

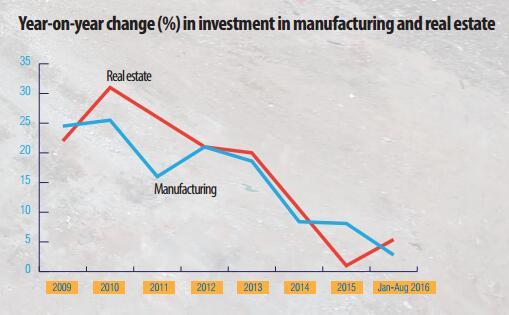

Manufacturing remains the main pillar of China’s competitiveness, but it’s being shaken as money rushes to real estate. In the first eight months of 2016, investment in real estate grew by 5.4 percent year-on-year, nearly double the 2.8 percent rise in manufacturing, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. According to data published on September 25 by the National Finance and Development Laboratory, thanks to the housing boom, non-financial listed companies restored growth in revenues and profits indicating generous profit from real estate related business and losses in other business.

Real estate has become a new hope for profit or even the last resort for survival for some companies outside the real estate sector. At the end of September, Nanjing Putian Telecommunications saved itself from being delisted on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange by selling two apartments in Beijing that had soared by more than 1,650 percent in value over the last decade. By mid-October this year, listed companies, ranging from sugar and cement makers to insurers and technology companies, disclosed nearly US$1.4 billion in purchases or planned of purchases of land, property or real estate company shares. Headlines like this reinforce public convictions that they would be better off investing in housing than manufacturing.

National leaders have often called for China to innovate if it wants to stay competitive. But high housing costs have pushed up the cost of innovation, including living costs for young talent, said Liu Shijin, vice chairman of the China Development Research Foundation (CDRF) under the State Council’s Development Research Center, at a forum in Hunan Province on September 24. “Some venture capital has shifted to real estate projects when they saw that returns there are much more attractive than in innovation start-ups,” he noted.

Beyond the economic costs are the social ones. As people buying their first homes enjoy lower down payment requirements and more favorable interest rates, many couples have divorced, bought a new apartment in the name of the person not named on their original house, and then remarried. However, cases in which husband or wife refused to honor their promise of remarrying were reported in this and previous housing frenzies. In 2013, the Jiangsu Provincial Supreme Court had to issue a statement, making it clear that the private remarriage contract does not affect the legal effect of divorce. The media also repeatedly urged couples not to compromise their family life for wealth.

It was these considerations that drove Party mouthpiece People’s Daily to issue a commentary on its WeChat account on September 26, warning “While the economic impacts of the soaring housing prices are yet to be seen, the social impacts are already evident.” It calls on the public and enterprises to pursue long-term meaning in life, and to build up real businesses, not to seek immediate windfalls by becoming “physical” or “spiritual housing slaves.” Otherwise, as the title of the piece went, “You’ll be homeless no matter how many apartments you have.”

But social media immediately mocked the idea, saying that hard work would still leave you homeless, and that the only way up nowadays was through the housing market. Yet the message actually reinforced the truth of the People’s Daily article’s conclusions; the housing bubble is corroding Chinese economic and social values. Analysts also increasingly recognize that innovation gave the US a way out of its own crisis, and that the bursting of the housing bubble in Japan, despite the rhetoric of the “lost decades,” still left it a prosperous, stable, and productive country.

People don’t want to listen to this message because nobody wants to risk their own place on the housing ladder, or to seem like a fool for not investing in a sure thing. Hard work and innovation seem like unappetizing prospects compared to the quick returns of the housing market. But the more that people continue to swim with the tide, the more devastating the effects when the tide goes out. Decisions that make immediate sense for individuals now may end up having catastrophic collective effects in the future.

Old Version

Old Version