Yet building a PSH station takes at least six to seven years. Gu Yu, vice president of WeView, a new energy storage company, told NewsChina that due to an investment trough, projects that broke ground in 2022 will not come online until 2030, making it hard to match the ramped-up new energy capacity.

“Some local governments we talked with expressed these concerns. After all, they can’t hold off on wind and solar installations until PSH stations come online,” Gu said.

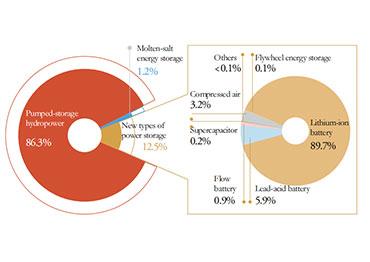

This brings new opportunities for energy storage solutions, notably electro-chemical storage, such as rechargeable batteries. By the end of 2022, lithium-ion batteries accounted for 94.5 percent of new power storage capacity in China, while compressed-air, flow battery and lead batteries accounted for 2 percent, 1.6 percent and 1.7 percent.

“Before the many PSH stations under construction go online between 2028 and 2030, new types of energy storage will grow rapidly as it’s much easier to find locations for them and the installation and testing cycles are much shorter – mostly two to three months, or half a year at most,” noted Liu Yong from the China Industrial Association of Power Sources.

What’s more, PSH cannot fulfill every demand. The China Energy Storage Alliance (CNESA) identified about 18 links in electricity generation, transportation, distribution and use that require power storage. Different storage solutions cater to different application scenarios.

“Lithium-ion batteries with high energy density that last one or two hours, for example, are suitable for small-scale distributed energy and user-side power storage. PSH, in contrast, provides longer duration [at least four hours] and larger capacity, making it ideal for adjusting base and peak loads. They complement each other,” said a staff member from a power storage company who requested anonymity. “One solution is not enough for the whole market.”

This person believes that with government encouragement, the scale of PSH installation will continue to increase, but its market share will gradually shrink. By the end of 2021, the share of PSH across the whole energy storage market fell below 90 percent. “Seven or eight years ago, it was 99 percent. At that time, PSH was a byword for energy storage.”

In July 2021, the NDRC and NEA published a guideline for new energy storage development that set a goal of increasing the installed capacity of new energy storage, like batteries, to 30 GW by 2025, eight times more than that of 2020. Since the latter half of 2020, many local governments and cities have encouraged projects that combine new energy and storage. By December 2022, nearly 30 provinces had released plans for new energy storage and development, according to the CNESA. The goal surpasses 60 GW, twice that proposed by the NEA guideline.

Liu Yong told NewsChina that in 2022 alone the new installed capacity of new types of energy storage increased from 2 GW to 5.6 GW nationally. Present capacity is already close to 10 GW.

Chen Haisheng noted that the ambitious plan reflects the provinces’ increasing requirements for power storage. But he warned local governments should not rush into mass construction as the business mode for the energy storage industry is yet to mature. He suggested they choose solutions that suit them best.

The dominance of lithium-ion batteries in the new energy storage market is challenged by surging costs, particularly the lithium carbonate needed to produce batteries, and the rise of other storage techniques.

Gu Yu said this year power storage companies do not lack orders, but capacity is insufficient. His company is bringing forward construction of flow battery plants, which uses chemical components dissolved in liquids to store energy and generate electricity, in Yancheng, Jiangsu Province and Zhuhai, Guangdong Province.

A person from a company engaged in compressed-air power storage (which works on a similar principle to PSH) revealed that compared to a few years ago, new technical solutions have gained more recognition. “There are already SOEs willing to invest in compressed-air stations. Such stations require high capital, so SOEs are the pillar of investment. But there are also private companies who hope to make initial investments and then transfer the project to SOEs,” said the person who spoke on condition of anonymity.

He admitted that compared to PSH stations, financing new types of power storage projects, including compressed-air storage, is harder without a clear pricing policy and stable business prospects.

In June 2022, the NEA and NDRC issued a notice encouraging developers of new types of power storage to participate in the market. Now many places are exploring possible business models. In Shandong Province, energy storage stations try to profit mainly from real-time trading of electricity and subsidies for providing load adjustment services.

“The installation of energy storage lags behind mainly because it is still exploring business models, and there’s so far no mature mechanism to recoup the cost,” Liu Yong said.

A report published by China Electric Power Planning & Engineering Institute in March shows that the installed capacity of new storage types is expected to surpass 50 GW by the end of 2025, four times that of 2022.

But many are still waiting for the catalyst that sets the market into full swing, just like the 2021 policy did for PSH.

Old Version

Old Version