The past two years have been tough for privately run dance companies, which have less support than those with government backing. Established in 2008 by Tao Ye, Duan Ni and Wang Hao, Tao Dance Theater is one of the few dance troupes that relies on performances for revenue. The avant-garde troupe was popular overseas, sometimes giving 40 international performances a year. It had a much bigger audience base overseas than in China. Some 90 percent of their performances were abroad, although Tao said he tried to change that.

When Covid-19 spread across the globe in 2020, their schedule was disrupted. Overseas shows were postponed or canceled, cutting off their primary source of income. They started touring Chinese cities in 2020 and became more popular, so they made creative adjustments to cater to domestic audiences.

But while Covid waves constantly ebbed and resurged, revenue was unpredictable. The company cared most about artistic vision, and had not engaged in more commercial activities such as selling merchandise or taking part in variety shows to promote themselves. To make ends meet, they tried providing dance lessons and establishing a clothing brand. Still, by the end of 2021, the troupe was heavily in debt.

The planned six-day performance at the Taihu Stage Art Center, an offshoot of the National Center for Performing Arts in Beijing’s Tongzhou District, was to be their biggest performance ever in China, a last-ditch attempt to get back on their feet. They planned to showcase all their works – 11 pieces performed chronologically, supplemented with a series of cultural activities including an artists’ dialogue and body art festival. Tao said that the on-and-off pandemic and the absence of art made him realize “the significance of cheering up live art again.” Attaching so much significance to the show, they spent an entire year preparing, recruiting dancers, training and rehearsing. Dozens of people were involved, including 16 dancers.

Tao told media that he hoped to strike a deal with a commercial backer to support his company. But pragmatically, he knew this level of cooperation was not realistic in China, particularly when the economy is struggling too.

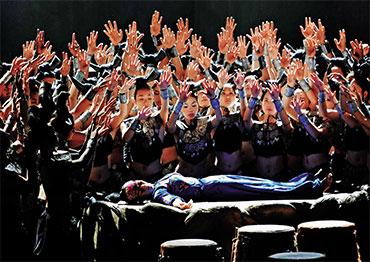

The past two years were also tough for Yunnan Imaging. In 2003, Yang Liping choreographed the large-scale original dance production with non-professional dancers from local villages. The next year the company toured China, and it was later staged in countries including the US, Australia and France.

The performance was popular and won prestigious Chinese dance awards. Audiences flocked to the show. Before the pandemic, the company performed in the theater of the same name in Kunming, to which the company moved in 2019, every night. As a drama representing local culture, it was high on the itineraries of tour groups. In 2019, the team’s income rose by 5.53 percent year-on-year.

But the pandemic put an end to all this as tourism was hit hard. In 2021, Yunnan Imaging was only staged 175 times, while costs rose by 420.35 percent after continuing to pay staff when they could not perform. Gross profits decreased by 219.89 percent, showing a severe financial deficit, according to the annual report of Yunnan Culture, a company founded by Yang Liping that of her Yunnan Imaging.

Unlike regular dance companies, most of the performers in Yunnan Imaging are villagers with no professional training. Being part of the company gave them their livelihoods and they are unlikely to get jobs in other performing groups. That made Yang even more upset. “It’s me who brought you from the farm to the stage many years ago. But now you have to leave,” Yang said in the video, sobbing.

Old Version

Old Version