An Iranian historian has brought to light more than 50 ancient Persian maps that add another layer of complication to ongoing territorial disputes surrounding the contentious South China Sea.

These maps labeled the waters to the east of the Indian Ocean as “China Sea,” with some calling the islands within the region “China Islands.” Chinese academics are holding up these maps as another piece of historical evidence to support China’s sovereign claims over the vast majority of today’s South China Sea.

The discovery of these maps emerged from a project spearheaded by Yunnan University Professor Yao Jide and University of Tehran Professor Mohammad Bagher Vosoghi. The duo led a team of researchers in collecting and studying any ancient Persian maps that included the labels “China” and “China Sea.” After translating them into Chinese and English, the team eventually plans to publish them in a trilingual atlas. Yao’s goals in this endeavor are to give more heft to China’s South China Sea claims and at the same time share these antique documents with the rest of the world. “These maps are priceless treasures, but they remain unknown to the public,” Yao told NewsChina.

Yao first heard about the existence of these ancient maps in March 2012. He was researching at a university in Beijing when he heard that an old friend, Vosoghi, was in town to give a lecture at Peking University.

When the two met up, Vosoghi said that while he was studying ancient Persian maps, he realized that “many of them mention ‘China’ and ‘China Sea,’” Yao recalled. This conversation single-handedly shifted Yao’s field of research.

Yao, concurrently the head of Yunnan University’s Southwest Asia Institute and its Iranian Studies Center, studied Sino-Iran relations as a visiting scholar at the University of Tehran from 2004-2005. He has conducted fieldwork around the Persian Gulf and in 26 of Iran’s 31 provinces. Shortly after the old friends discussed the Persian maps, Vosoghi sent Yao a handful of examples for him to examine, and Yao immediately recognized their historical value. “These ancient maps could become a powerful piece of historical, thirdparty evidence that proves China’s sovereign rights over the islands in the South China Sea,” Yao said.

In the months after Yao and Vosoghi met in Beijing, the disputed maritime region had become a ticking time bomb. China and the Philippines held a drawn-out maritime standoff near Huangyan Island (Scarborough Shoal) in April 2012. Conflict with Vietnam led to anti-China protests in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi later that year. Finally, in January 2013, the Philippines launched its international arbitration case in the Hague challenging China’s territorial claims. The region’s intensifying atmosphere drove Yao to push forward with his map-based research into the historical basis of China’s claims.

Yao and Vosoghi officially commenced the “South China Sea Ancient Maps Project” in April 2013. As principal researchers, they managed a small team of younger academics from both China and Iran. The Yunnan provincial government gave them grants to fund the endeavor the following year.

The team members quickly outlined a plan to make the atlas a reality. For the project’s initial stage, Vosoghi would take charge of digging through Iran’s libraries and archives to locate any ancient Persian maps that mentioned both “China” and “China Sea,” then analyze and annotate them. The annotations would then be translated into Chinese by two Persian-language experts. Yao would proofread and revise the Chinese text, then examine the ancient documents in a historical and geographical context. Finally, the revised Chinese version would be translated into English and the trilingual atlas would be ready for publication.

Over the next two years, Vosoghi collected more than 50 ancient maps that had been stored in special preservation areas in institutions such as the University of Tehran; the Library, Museum and Document Center of Iranian Parliament; and the National Library and Archives of Iran. He finished annotating the maps last February. The maps were drawn over a period of about 700 years, from the 10th century to the 17th century.

The language barrier remains one of the research team’s biggest challenges. Bai Zhisuo, a renowned Persian-language expert with the Iranian embassy in Beijing, is responsible for the Persian text’s Chinese translation.

He told NewsChina that decoding historical place names has proven especially arduous.

He said there were great differences in the pronunciations between place names in Persian and Chinese; for instance, in Persian the Chinese city of Guangzhou sounds like “Khanfu” and Vietnam’s Hanoi sounds like “Iojin.” As a result, transliteration was not a possibility. Instead, “it’s necessary to consult Chinese historical and cartographic materials to see what these places were called in Chinese documents,” Bai said.

Another major challenge stemmed from the fact that ancient Persian cartographers used several different terms to refer to China, such as “Large China,” “Inner China” and “Outer China.” When he encountered particularly thorny terminology, Bai turned to researchers in Iran to ensure an accurate translation. Now the 50-some maps have all been analyzed and translated into Chinese.

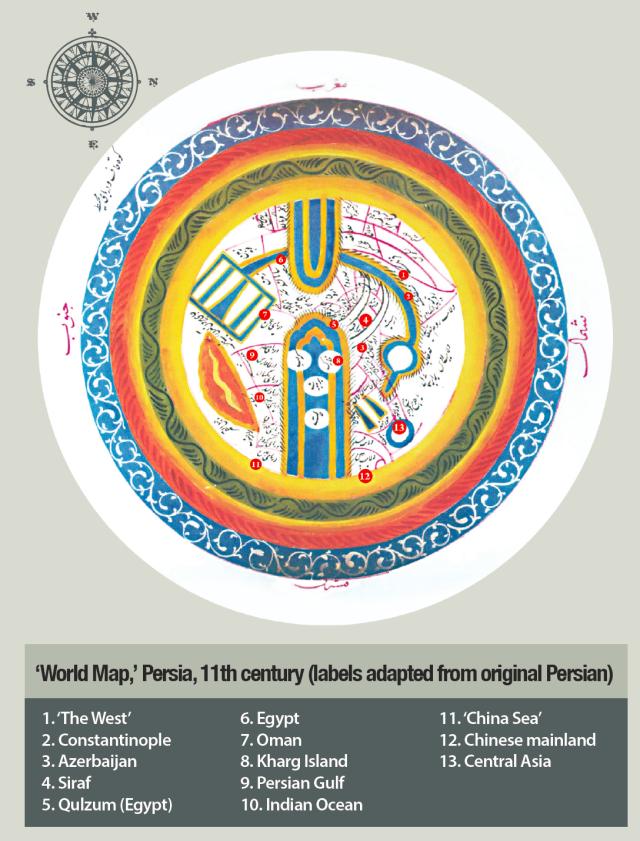

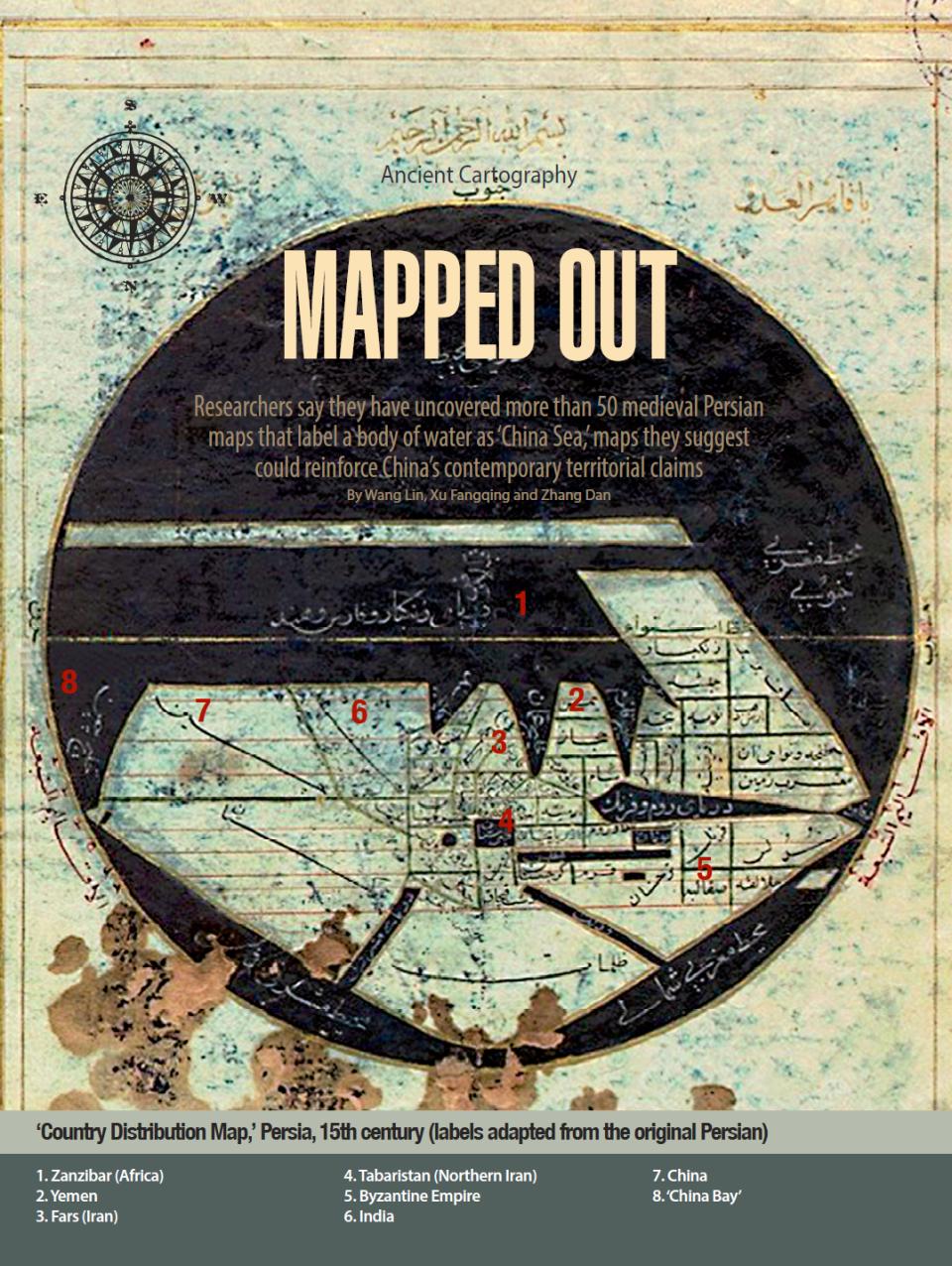

Yao showed NewsChina a photocopy of one of them, an 11th-century document titled “The World Map.” The map was drawn in yellow, white and blue and labeled the waters to the east of the Indian Ocean were labeled as “China Sea.” Also included in the collection is a map drawn by famed 15th-century mathematician and astronomer al-Kāshī. Titled “Country Distribution Map of the World,” the map is the first to label the body of water to the east of the Indian Ocean as “China Bay.” According to Yao, although the ancient maps are not accurate in comparison with the meticulousness of modern versions, it is still evident that the body of water in question, first labeled as “China Sea” and then “China Bay,” lies between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. “This has very real significance today in understanding China’s traditional coastal areas and territorial seas,” Yao said.

At the same time, Yao acknowledged that deciphering these ancient maps requires more work and analysis. Because the maps are several hundred years old, the methods used by their cartographers vary greatly, making it difficult to determine exactly which areas of the ancient charts correspond with the geographic regions of today.

Vosoghi has asked cartography experts to conduct comparisons, but these attempts have yet to yield satisfactory results. The research team is still searching for a workable solution. “This has been a major regret for me,” Yao said. But he is determined to produce an academic work that is as accurate as possible. “We want to provide a comprehensive and truthful record and interpretation so we can show the profound historical value of this group of ancient maps,” he said.

Yao already knows what he will work on after the atlas’s publication. He will seek out more ancient maps that include China, either in Iran or other Middle Eastern countries, to continue the team’s research. “Despite the difficulties, we will keep trying,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version