fter learning I’ve lived three years in Beijing and four in Shenzhen, strangers are quick to survey me. I usually equivocate with praise for the people of the capital and the beauty of this seaside metropolis. In reality, there’s much in common.

The same love of the large occurs north and south, malls and high-rises soaring to the sky with the same red underwear drying on the balconies. China’s days are scored to the same soundtrack: calming tai chi tones, shouts into mobile phones, the hammering of unending construction, and the high-volume hustle of aunties dancing after dinner.

Of course the weather is an obvious difference, at least in winter. While Beijing shivers as the cold seeps from concrete floors into one’s bones, this subtropical corner experiences just a month or two with hats and gloves. It’s usually brief and mild, sadly never enough to kill all the pests. So it’s more common in Shengzhen to discover unwelcome visitors crawling through the kitchen. It’s probably also why all my southern friends scrupulously follow the restaurant ritual of bathing each dish, glass and chopstick with boiling water.

But in the hot months, we all sweat together. In sweltering summers – increasingly fierce everywhere, thanks to cataclysmic climate change – men north and south roll their shirts above the belly to play cards, swill baijiu (strong liquor), and feast on fiery hot crawfish. If it’s barbecue, southerners tend to like it sweet in the Cantonese style, versus the cumin-coating of the north. But no lamb down here, thanks: many of my southern friends can’t stand the taste of mutton, even if they’ll devour anything from the sea. But besides abundant dim sum, the food here is largely the same. Breads are steamed or baked, stuffed of fried, and everyone cherishes dumplings, rice, and noodles with a gusto that unites all who speak Chinese.

Or, I should say, the extended family of languages we call Chinese. Across the south I hear echoes of the old domains that now constitute China. Melodious Cantonese is pervasive here in old Canton – with the exception of Shenzhen, the diverse product of internal immigration. But in Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong Province, and beyond, the old language is the only one the old folk know. The same seems true in Shanghai, Sichuan, and among the peoples further west. While Beijing remains the ancestral home of Putonghua, that emblem of the unity of New China, the polyphony of the south reminds me of what rich cultures constitute this mighty nation.

The “self-combed sister” comes to mind as a particularly southern cultural innovation. When silk technology improved during the Ming Dynasty, new mulberry trees south of the Yangtze improved the region’s fortunes. One consequence was this rising class of wellpaid working women, forging a new role as unmarried matrons acting as patrons to siblings and other dependents. For three centuries they flourished from ancient Shunde throughout the Pearl River Delta, offering a model of female autonomy that still lives on in stereotypes of fierce southern women and their compliant men.

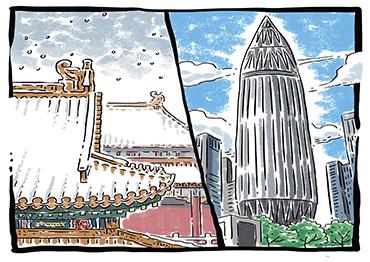

The north and the south of the country each represent a strand of this country’s history that, woven together, have forged the strength of modern China. In simplest terms, it’s where they turn their gaze.

The industrial north has long looked inward, to the coal of its mountains and to Beijing, seven times a grand capital and seat of the officials who operate this country’s vast bureaucracy. But in Shenzhen and the south generally, the gaze looks out the wider world. For countless generations these seaside provinces have launched scores of emigrants, reaching across the globe in a web of connections that have made just as powerful a contribution to China’s place in the world. This region has long seen the opportunity held in the ocean and the peoples beyond.

Shenzhen, for its brief four decades, had its eye on Hong Kong, just across the narrow bay and the wider borders of time, law, and culture. Learning from that powerhouse of finance and shipping has brought 10,000- fold growth to this metropolitan assemblage.

But in the north the winding hutongs, once so messy and vibrant, are now as clear and quiet as the streets closed for centennial celebrations. The eyes are cast inward again, to the man at the microphone, to the Partydriven century behind us, and the promise of another to come.

Old Version

Old Version