With ancestral roots in Wuwei, Anhui Province, Luo sees Yonghe, where he lives, as his “temporary hometown.”

Now a district of New Taipei City, Yonghe was once a town of new arrivals from the mainland. The town had labyrinthine lanes lined with buildings from the Japanese occupation (1895-1945).

When he was a kid, Luo saw the mainlanders as “aliens.” They spoke in dialects that sounded foreign to him. While wandering through the old lanes, the boy would observe these “aliens” playing chess, chatting and humming the hits of pop songstress Teresa Teng. It was not until Luo went to university that he realized he was also a child of aliens.

Luo claims that unlike writers of his father’s generation, who witnessed drastic social and political changes, his generation had an “experience deficiency.”

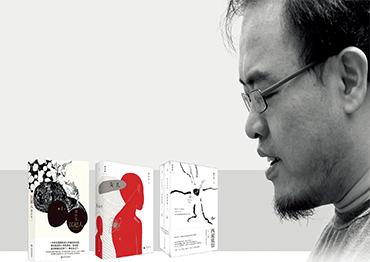

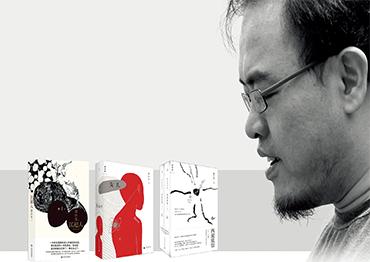

He has always admired mainland writers such as Ah Cheng and Liu Zhenyun, who present Chinese society in a realistic and penetrating way through personal experience. But Luo’s own writing has no trace of 19th-century social realism, rather it is influenced by 20th century modernism and postmodernism.

Luo’s writing is introspective, often delving into subjects such as alienation, loneliness and identity crises. He compares himself to the crow in Aesop’s fable “The Bird in Borrowed Feathers”: He greedily absorbs all kinds of stories, whether from reading or others’ experiences.

David Der-wei Wang, professor of Chinese Literature at Harvard University, describes his style as “pseudo-autobiographical intimate narratives constituting a relay race of fragments, filled with uncanny and decadent imagery and undergirded by an immoral worldview.”

While at college, Luo devoured modern literary classics by big names such as Franz Kafka, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Italo Calvino, Marcel Proust, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Kawabata Yasunari and Oe Kenzaburo. His extensive reading was the foundation for his dedication to Western modern literature.

Luo also borrows stories from others. He loves to drink with all sorts of people, hear their stories, and blend them into his own writing.

“Novelists have the strongest sense of roleplay,” Luo said. “They can switch roles according to situations.” He quoted Czech writer Milan Kundera: “Novelists draw up the map of existence by discovering this or that human possibility.”

Luo attributes the themes of alienation and migration in novels such as Tangut Inn, which combines science fiction with postmodern literature, and the quasi-autobiographical We, to feeling like an outsider while growing up in Taiwan.

He spent four years writing Tangut Inn (2008), during which he suffered three bouts of depression. The book weaves the history of the Tangut people’s mass exodus after Mongol leader Genghis Khan conquered the Western Xia Kingdom in the 13th century through the story of protagonist Tunik, whose grandfather and father fled to Tibet after the end of Chinese Civil War (1945-1949). As the two storylines intersect, they conjure experiences of fear, trauma and exile.

Luo said the descendants of mainlanders will eventually assimilate completely and their community will fade away, sharing the same fate of the Tangut people who built the Western Xia Kingdom.

Many readers see a continuity in Luo’s writing. Some have commented he “has been writing the same book his whole career.” Luo takes it as a compliment.

“It’s a pretty beautiful line, isn’t it? I’d like to carve it on my tombstone,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version