China’s foreign policy had a tremendous impact on its tastes for imported film, which in turn shaped people’s attitudes toward international relations

Across human history, art, commerce and politics have inevitably intertwined. In the past 70 years, the Chinese cinema landscape experienced dramatic changes in response to the political and cultural upheavals of Chinese society, as well as its relationship to the world. In return, cinema reshaped Chinese people’s perception of their own country and the outside world. NewsChina offers a review of the interplay between diplomacy and cinema to gain a better understanding of an important aspect of the history of modern China.

1950s: ‘Leaning to One Side’

Emerging from the devastation of World War II and a bloody civil war, the new People’s Republic of China (PRC) faced a turbulent domestic and international environment. As the iron curtain fell in the wake of WWII, which led to the Cold War, China adopted a “leaning to one side” policy, joining the socialist camp and severing ties with Western countries, especially the US. The former Soviet Union was the first country to grant diplomatic recognition to the PRC and in 1950, the two countries signed the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance.

the film industry came under direct control of the government, China’s joining the Soviet camp was clearly manifested in the cinema landscape, which was dominated by imported Soviet movies. Between 1949 and 1957, 468 films from the Soviet Union were introduced to Chinese audiences, with at least nine of them attracting more than 25 million viewers, a huge number given that China was predominantly agricultural back then.

While the period is now often portrayed from a dehumanized perspective as an era of massive propaganda derived from political realism, it was fondly remembered by the generations who grew up in the 1950s as a time imbued with socialist romanticism and revolutionary idealism and passion.

Just like the Hollywood movies shown in later periods led many Chinese viewers to long for a Western lifestyle and envision an “American dream,” Soviet films presented a cheerful vision of the Soviet presence as China’s future, which helped to transform socialism from an abstract concept into a desirable future. It was effective in mobilizing the Chinese people to follow the model of Soviet ideals and experience to transform China from its feudal and semi-colonized past into an industrialized socialist country.

At the macro-level, movies like Lenin in October (1937) and Lenin in 1918 (1939), perhaps the two most watched Soviet films, which focused on Vladimir Lenin’s role in the Russian Revolution (1917-1923), directly linked the revolutionary experience of the two countries. At the micro-level, films such as The Kuban Cossacks (1950) and The Tractor Driver (1939) presented an ideal dreamland far ahead of the material life of ordinary Chinese at the time, showing exotic things like ice cream, wine, lipstick, tractors and heavy machinery on screens for the first time. The prominent role of women in these films also helped China to launch a nationwide reform to elevate women’s status in the country. Liang Jun, China’s first female tractor driver who trained in 1948 and was featured on a 1962 one-yuan banknote, said she was inspired by a Soviet film she saw in 1947 when she was 17.

Another major event that had an enduring impact on China’s psyche toward the world, especially the US in the 1950s, was the Korean War (1950-1953). Antagonizing the Sino-US relationship and pushing China deeper into the Soviet camp, the war also left its mark on China’s cinema history. In 1956, Shangganling, a war film depicting Chinese soldiers successfully defending a ridge called Shangganling for 42 days in 1952 became an all-time classic. Known as the Battle of Triangle Hill by the Americans, the campaign was a bloody defense with many casualties against US and South Korean forces, who had absolute superiority on the ground and in the air. Over the following decades, the theme of the film, often dubbed the “Shangganling spirit,” evolved to become a symbol of China’s fighting spirit against seemingly more powerful imperialist forces, often the US.

Even after China’s opening-up in the late 1970s, the movie routinely re-broadcast on Chinese State TV channels, especially at times when the relationship sours between China and the US. It was broadcast when US President Donald Trump’s administration announced new tariffs on Chinese imports following the collapse of the trade talks between the two countries in May.

1960-1972: China-Soviet Schism and Cultural Revolution

China’s infatuation with the Soviet Union was short-lived. Starting in 1958, the relationship took a downturn as the two sides fell into disputes on issues ranging from border disputes and naval cooperation to interpretation and application of orthodox Marxism, especially regarding the socialist camp’s approach to dealing with the US.

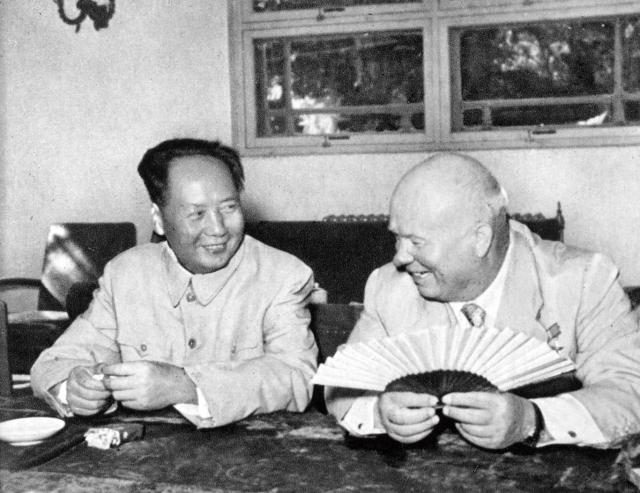

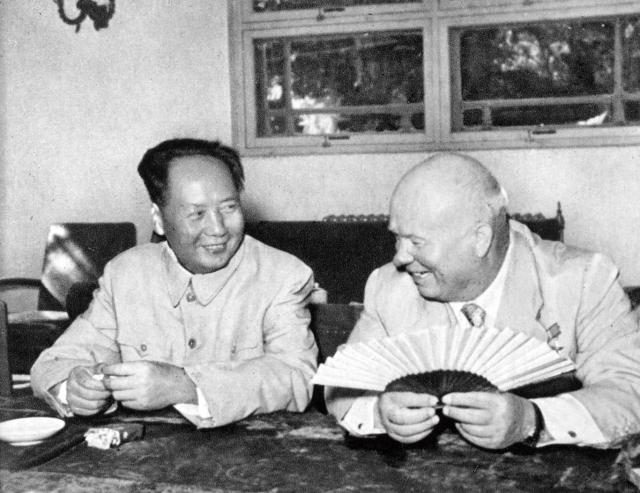

While the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev started to adopt a policy of “peaceful co-existence” with the Western world, China criticized it as revisionism that betrayed the interests of Eastern bloc countries. In 1961, after Beijing openly denounced Moscow as “revisionist traitor,” the Soviet Union withdrew all personnel and material support from China. The hostility between the two countries lasted until the 1970s and the two sides fought two brief but bloody border skirmishes in 1969.

The hostility between the two governments inevitably had a major impact on bilateral cultural exchanges and cinema. In the 1960s and 1970s, the number of imported Soviet films dropped substantially, though some whose content was considered to be in accordance with orthodox Marxism still found their way to China.

By contrast, China started to import films from other socialist countries such as Hungary, Poland and Romania. But the ones that had the most influence were from Albania. Although a small country on southeastern Europe’s Balkan Peninsula with less than three million people, it enjoyed a special status in both China’s diplomatic and cinema history.

Breaking its diplomatic relationship with the Soviet Union in 1961, Albania was one of the few countries that sided with China during the China-Soviet schism and was the only country that voiced support for the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). To support its defiance against Moscow, China offered the small country about US$125 million in food, raw materials and equipment in the 1960s, a huge amount given China’s own financial difficulties. The China-Albanian friendship resulted in mass dissemination of Albanian films, mostly war-themed, which offered a small window into Europe for Chinese people.

During the period, China’s relationship with North Korea also reached new heights after China pulled its troops out of North Korea in 1958, which led to an influx of North Korean films in the 1960s and early 1970s. The Flower Girl (1972) was allegedly written by the country’s first leader Kim Il-Sung while he was in prison in the 1930s. Set at that time, it tells of an impoverished family at the time of the independence guerrilla movement against the Japanese. Ending with a rousing call to arms, it was extremely popular in China and became the most influential North Korean movie shown in the country.

Following a meeting in 1965 in Beijing between Chairman Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh, at the time leader of North Vietnam’s independence movement, China started to support Vietnamese troops against the US on a massive scale. It was not a coincidence that at least 12 Vietnamese films were translated and dubbed during the period between 1962 and 1974, roughly the same period of the Vietnam War, though none of the films gained any considerable influence in China.

1978-1989: Liberalization, Opening-up and Western Influence

After more than a decade of international isolation and political turmoil, Mao started to rethink his diplomatic approach to the Western world. In 1972, former US president Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijing marked rapprochement between China and the West. In 1978, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping launched the reform and opening-up policy and China and the US established a formal diplomatic relationship, which opened the door for cultural exchanges between China and the West, leading to the kaleidoscopic development of China’s cinema world.

The first country to have a major impact on China’s cinema was not the US, but Japan. With the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Japan in 1972, Japanese films started to be screened in China in 1970s. They were immediate hits thanks to geographic proximity and cultural connections.

One of the most watched Japanese films during the period was Manhunt (1976). While the film only saw mediocre box office returns in Japan, it became hugely popular in China in 1978 as one of the first foreign movies released after the Cultural Revolution. Lead actor Ken Takakura became the most famous foreign celebrity throughout the late 1970s and 1980s.

But the popularity of Japanese films was soon overshadowed by resurfacing disputes on Japan’s alleged revisionist approach to its wartime crimes. Japan made several amendments to school textbooks about historic facts several times in the 1980s. The issue, along with territorial disputes would continue to have a major impact on political ties and cultural exchanges between the two countries.

As China and the US signed agreements on cooperation in science, technology and cultural cooperation followed by Deng Xiaoping’s landmark visit to the US in late 1979, China opened its market to American films, which at once captivated the Chinese. Films like First Blood (1982), E.T. (1982), Breakin’ (1984), Terminator (1984) and the Star Wars series caused sensations among Chinese moviegoers who eagerly flocked to this new world of cinematic opportunity. As reform and opening-up policies led to the liberalization of control over local TV stations, TV stations started to buy older and cheaper American films released five years or 10 years earlier to broadcast. Moreover, along with technological development such as the emergence of videocassette players, a huge number of both legal and pirated copies of Hollywood films became widely available to Chinese viewers.

At the same time, Hong Kong films, especially gangster films, crime dramas and kung fu comedies became popular in China and worldwide.

The film industry in the Chinese mainland began to gradually recover from the devastating impact of the Cultural Revolution, with the 1980s often dubbed the most audacious period for Chinese cinema. Wreaths at the Foot of the Mountain (1984), for example, is still the only film covering the bloody border war between China and Vietnam fought in 1979.

A scene from the film Shangganling

A scene from the film Echoes on the Shore

Hong Kong actor Chow Yun-fat (left) in The Replacement Killers

Representatives from neutral states of Switzerland, Sweden, Poland and Czechoslovakia hold talks over the transfer of prisoners from the Korean War at Panmunjom, August 1, 1953

Chairman Mao Zedong talks with Nikita Khrushchev in Beijing, July 30, 1958

Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping meets Henry Kissinger during his visit to the US, February 5, 1979

Titanic

Avatar

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Chinese President Jiang Zemin attends a press conference with US President Bill Clinton in the Washington DC, October 29, 1997

The National Stadium (Bird’s Nest) during the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games, August 8, 2008

US President Barack Obama announces his “Pivot to Asia” foreign policy in Washington DC, January 5, 2012

1990s and 2000s: Commercialization and China-US Interdependence

The honeymoon between China and the US seemed to have come to an end with the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989.

While the US may have ignored, if not encouraged the spread of pirate copies of Hollywood movies in the hopes of influencing Chinese social values, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which effectively ended the Cold War with the US coming out as the victor, led the US to shift its priority from strategic to economic and commercial considerations regarding Sino-US film cooperation.

In the 1990s, the US started to pressure China to curb piracy and open the Chinese cinema market. Eventually, the two sides signed an agreement in 1993, according to which China would impose a quota on the number of Hollywood films that could be shown in Chinese theaters on a revenue sharing basis. The quota started at 10 per year in 1994, which later increased to 20 films per year in 2002, and then 34 films per year in 2012.

While the agreement was far less than Hollywood had hoped for, it kickstarted a new era which marked cooperation and exchange between the film industries from the two countries. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Hollywood films played a dominant role in China’s box office. Out of the 15 years between 1994 and 2014, Hollywood films topped the box office in 10. These included True Lies (1994), Titanic (1997), 2012 (2009), Avatar (2009), and the Transformer series. Titanic was listed as the highest-grossing film of all time in the Chinese market for 12 years.

In the meantime, there was a surge of Chinese films on the international market. Chinese moviemakers presented an aesthetic novelty for Western audiences curious about the world’s oldest continuous civilization that had been isolated from the world for much of its recent history. Among the award-winning Chinese films during this period were Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern (1992), The Story of Qiu Ju (1992), To Live (1994), Not One Less (1999), The Road Home (1999) and Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (1993). Chinese movie stars such as Jackie Chan and Jet Li made the move to Hollywood with a slew of successful starring roles.

Yet for many Chinese critics, many of the award-wining films of this time specifically catered to Western tastes by focusing on politically sensitive events and periods, and the success of Chan and Li was also still built upon Western stereotypes of the Chinese, with Jackie Chan being the comedy Asian sidekick with an accent who can do kung fu and Jet Li being a cold-blooded and robotic martial arts hitman. Audiences still loved them however.

At the end of the 1990s and in the early 2000s, some films defied this categorization. The Replacement Killers (1998) was the Hollywood debut of Hong Kong actor Chow Yun-fat, one of the most popular movie stars in China. Chow still portrayed an Asian killer, but presented a much more suave, sophisticated and dignified image with a characteristic Chinese confidence. Then in 2000, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, a martial arts film with a unique Chinese aesthetic directed by Taiwanese director Ang Lee achieved unprecedented success for a Chinese film in the US market. With a gross box office of US$213.5 million and gaining 10 Oscar nominations, it was the first Chinese-language film to find a mass American audience.

To a large extent, this golden period in Sino-US cooperation in cinema reflected the general development of the bilateral relationship at a time when the two countries considerably deepened their economic and trade ties. During Chinese President Jiang Zemin’s keynote visit to the US in 1997, the two sides agreed to strengthen cooperation toward “a constructive strategic partnership in the 21st century.” In 2000, US President Bill Clinton’s administration granted China the status of permanent normal trade relations, which paved the way for China to join the World Trade Organization in 2001.

But this golden period for movie success was also short-lived. After Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004), both directed by Zhang Yimou, saw modest success in the US market, the influence of Chinese films and Chinese celebrities rapidly declined in the late 2000s. One reason was that after years of exposure, the aesthetic novelty of Chinese films was pushed to its limit. Moreover, as China’s film market became bigger and more commercial, China’s moviemakers started to shift their focus from seeking Western recognition to catering to the needs of domestic audiences, who had developed different tastes and preference to Western moviegoers.

But even more significant was the apparent change in mood between the two countries in the late 2000s. As China’s economy grew rapidly, it was no longer the poor, harmless country it was in the 1990s and was increasingly perceived by the US as a competitor that posed a potential threat.

2008-Present: Nationalism and Rivalry

It is hard to pin down a specific year when the mood between the two countries took a turn, but 2008 may be the best pick. Not only did China hold the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, an event considered a milestone in China’s projection of its soft power, China also surpassed Japan to become the largest holder of US debt at around $600 billion. The year also saw the US battling the 2008 global financial crisis, while China was able to withstand the impact through a massive stimulus package.

In 2010, China surpassed Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy. The US first responded with a “Pivot to Asia” policy under the Obama administration and then more recently launched a massive trade war with China fueled by the nationalism of the Trump administration.

To a large extent, the dynamics of diplomacy were reflected in the film industry. From the late 2000s, China’s film market experienced phenomenal growth, with the total box office increasing from 4.3 billion yuan (US$606m) in 2008 to 60.7 billion yuan (US$8.5b) in 2018, with an average annual increase of 35 percent. With an ever-increasing domestic market, Chinese films appeared to vanish from the international cinema landscape, focusing entirely on the domestic market. In the 2010s, domestic blockbusters started to challenge the dominant role held by their Hollywood counterparts in China.

In 2015, with a gross box office of US$384 billion, Monster Hunt, a Chinese fantasy comedy movie replaced Fast and Furious 7 (2014) to become the all-time high-grossing film on the Chinese mainland market, the first domestic film to do so since 1995.

The current record is held by Wolf Warrior II (2016) at US$1.08 billion. Based on the evacuation of Chinese nationals conducted by the Chinese navy during the 2015 Yemen civil war and featuring a China overseas military operation, the film was considered to symbolize the rising nationalism. The success of another film, Operation Red Sea (2018), based on the same event, reaped a box office US$579 million and further reinforced this perception. In the meantime, Chinese started investing in Hollywood. In 2016, Wang Jianlin, founder of the Wanda Group, bought Hollywood studio Legendary for US$3.5 billion, leading to concerns over China’s cultural “infiltration” in the US. The company’s first film The Great Wall (2016) aimed to appeal to both Chinese and Western audiences and bridge the world’s two largest film markets but gained only modest success and was critically panned.

As Chinese companies increased their investment in Hollywood movies, Chinese celebrities maintained a presence. But different to the 1990s, Chinese characters in Hollywood movies now started to speak much more Chinese with much more and often unpleasant authority and rigidity. In many cases, Chinese characters are only included in the version released in the Chinese market.

Back in China, domestic films continue to consolidate their position. Built upon national pride over China’s achievements in space exploration including the historic landing of the Chang’e 4 probe on the dark side of the Moon on January 3, The Wandering Earth (2019) became the first domestic science fiction film to obtain major success with a box office of US$700 million.

Then in summer, Nezha (2019), an animation fantasy adventure film based on the popular mythological child deity, surprised everyone by beating both The Wandering Earth and Avengers: Endgame to become the second-highest grossing movie of all time in China.

To many Chinese commentators, the success of Chinese films in genres previously monopolized by Hollywood such as sci-fi and animation reflects a rising cultural confidence among the Chinese people.

With the trade frictions and strategic rivalry between China and the US set to persist in the foreseeable future, the interplay of diplomacy and cinema will continue to unfold. In return, cinema will continue to shape the perceptions of Chinese people of both themselves and their relationship with the rest of the world.

Old Version

Old Version