Perhaps China’s most successful film developer, Zhang Zuo has spent more than three decades perfecting the dying art of bringing a photo to life

Entering Zhang Zuo’s darkroom is like stepping into another world.

Close the purpose-built door behind you and any light and noise from the outside vanishes instantly, making an old safelight’s feeble glow the only thing separating you from complete blackness. A chemical smell suffuses the air. Time almost slows to a stop in this 10-square-meter room, which is so quiet that the only audible sounds are your own breath and a photo enlarger whirring in the background.

Zhang has spent more than 30 years in darkrooms like this. As one of the finest film developers in China, he has made prints of some of the most iconic black-and-white images in the history of Chinese photography, including Xie Hailong’s “I Want to Go to School,” a well-known photo of a wide-eyed, eight-year-old girl. He is the specially appointed cooperative partner of a great many renowned photographers and museums.

Most of the time, colleagues call him “Master Zuo.” Zhang honed his film photography skills during the nationwide craze in the ’80s and ’90s, then stood aside as the invasion of digital technology left film in the dark. Now the tradition of developing film by hand is in danger of disappearing. Only a small number of photography enthusiasts still practice the craft. Yet no matter how tremendously the outside world changes, Zhang remains in his darkroom, dedicating his efforts to saving his dying art form from extinction.

Mastery Zhang, a slight man with precise hands and thick glasses, reaches over a tray of water to turn on an old radio ensconced on the shelf. A soft melody permeates the room.

Throughout his long days and nights in the darkroom, the radio has been his only companion.

Soak the film, develop the film, halt development, rinse – Zhang’s movements are fluid, well oiled over more than three decades of experience. Although darkroom work may seem monotonous and lonely, he remains completely focused, for any slight error may have irreversible consequences.

There is a saying in the Chinese photography industry: “A good photo is three parts shooting and seven parts printing.” The darkroom process greatly affects the quality of a picture. Film developers’ skills and expertise are significant, but their accurate interpretation of the photograph’s mood, character and essence is even more important in realizing the photographer’s true intentions.

Jin Yongquan, renowned documentary photographer and former head of photography at China Youth Daily, spoke highly of Zhang’s craft and insightful understanding of the art. “He uncovers many remarkable details that you don’t even see while shooting,” Jin said. “If it weren’t for him, these details would be lost forever.” In 2001, Zhang developed one of Jin’s

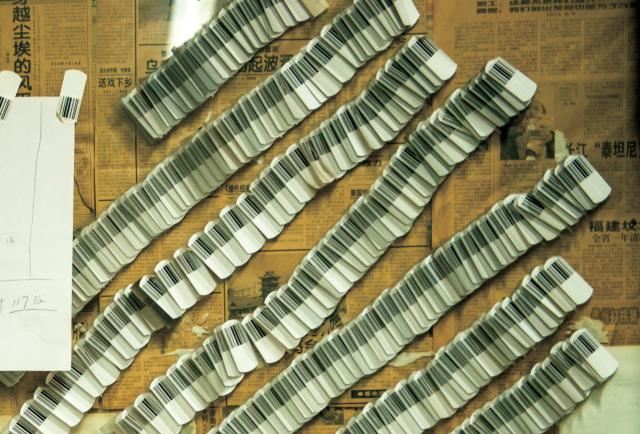

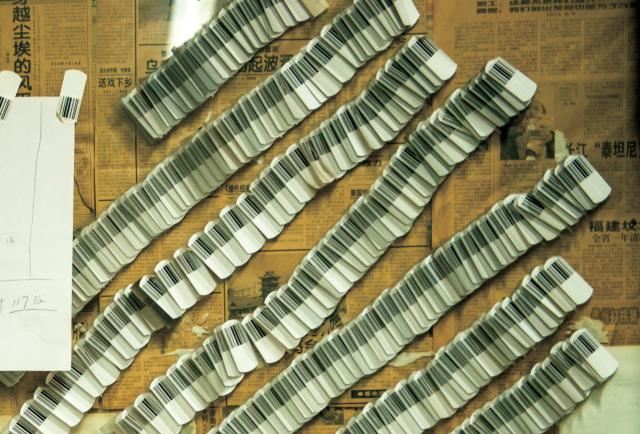

Tags on the wall of Zhang Zuo’s darkroom

most famous photo series, “Chinese Nuo,” which documented a ritual performed by religious practitioners in some minority ethnic groups in southern China. Based on his own experiences, Zhang made suggestions to Jin about which aspects in the photos needed to be further highlighted. Because of Zhang’s efforts, the color of the formerly pale sky in the photo “Nuo God and Goddess” became much softer and more layered, eliciting a stronger visual impact. The photo series, first exhibited at the Pingyao International Photography Festival in 2001, quickly gained international acclaim and was shown in Paris’ Centre Pompidou in 2003.

Jin is not the only photographer who has benefited from Zhang’s keen eye. Several years ago, a reporter who once interviewed Zhang said: “If one day someone were to hold an exhibition exclusively displaying all the black-and-white photos Zhang Zuo has developed, it would be a magnificent sight, a collection of iconic masterpieces created by the most renowned photographers in modern China.” ‘Fate’ Zhang grew up in Beijing. After high school, he was sent to the countryside to toil beside rural villagers for “re-education,” along with millions of other urban youths during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). When Zhang returned to the capital after two years of labor, he was assigned to work as a mason for the housing management bureau in Beijing’s Chongwen District. His life became an endless cycle of piling up bricks, building walls and drinking alcohol. He found it arduous and unstimulating.

With the launch of Reform and Openingup in the 1980s, China witnessed a surge in cultural pursuits as people hungered to fulfill themselves spiritually. One of Zhang’s coworkers bought a camera and decided to learn photography. Zhang was intrigued. After much consideration, he spent a great sum of money, equal to one year’s salary plus an amount borrowed from his parents, to buy a Konica camera. Although he started off by taking casual snapshots in parks with friends, Zhang became instantly addicted to photography.

He fell in love with it.

Both his skill and infatuation deepened quickly. He scrimped to once again save up an amount equal to his annual salary and bought rudimentary darkroom equipment to set up at home. Every day, as soon as he came home from work, Zhang would spend hours delving into the craft of hand-developing photos, trying to mix chemicals and process negatives on his own.

In 1986, Zhang won first place in a Beijing photography competition, attracting the attention of Xie Hailong, a photographer who worked at the Chongwen District Cultural Center and helped host the competition. Xie tried to persuade Zhang to quit his construction job and work with him in the cultural center. For Zhang, this was a painful choice

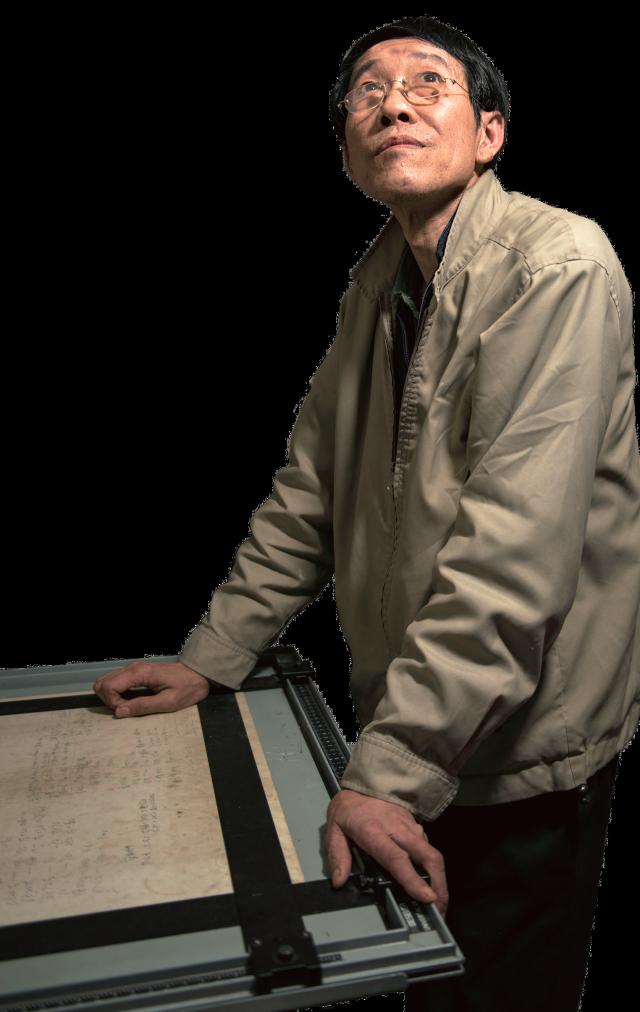

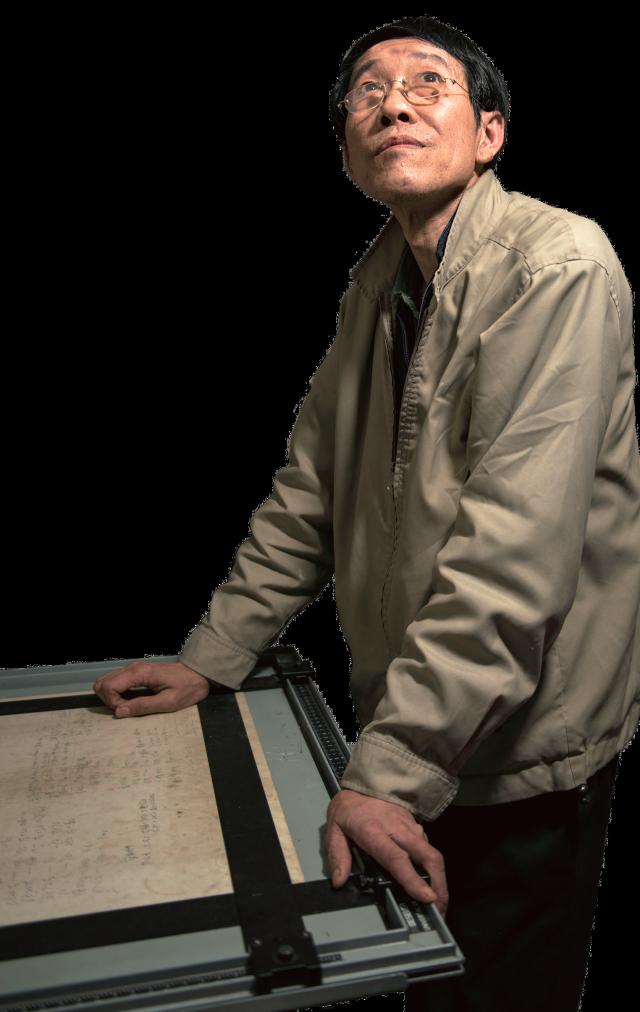

Zhang Zuo points out subtle differences in two prints of the same photo

to make – leaving a secure job in China’s centrally planned economy required so much courage that few people dared to take the risk.

But Xie’s words awakened him: “Do you really want to waste your life stacking bricks and building walls instead of doing what you love most?” Zhang then elected to formally begin a professional career in photography.

From then on, he said, “it was like my fate was decided.” Zhang worked in the cultural center for eight years as a film developer, gradually making a name for himself in photography communities. In 1992, China Youth Daily hired him to work in the paper’s darkroom as a photo developer.

At that time, there was only one other person working in the darkroom, and the workload was so massive they produced at least 30 prints a day. After they finished the newspaper’s prints, Zhang would either volunteer to develop photos for his colleagues or print his own negatives by using some of the leftover paper. In one year’s time, Zhang developed thousands of rolls of film and went through 20 boxes of paper – a total of 20,000 sheets.

When the State-run Xinhua News Agency held a national news photography competition in 1994, Zhang was put in charge of printing China Youth Daily’s entries. The photos he produced ended up winning more than half of the awards. Word of “Master Zuo’s” skill immediately spread. This was the first time in his life that Zhang felt his talent as a film developer was being recognized.

And it’s a talent fueled by dedication.

Zhang lives in a world with only three colors: “Everything is black, white and gray.” When he takes a walk outside, he often plays a color game with himself by imagining what he sees in black and white; a red jacket becomes dark gray, a yellow cat becomes light ash. Zhang is constantly contemplating how the objects he sees would develop in a photo, how he would frame the image and how much he would adjust the tone.

“Most of the time it’s not a matter of skill, it’s a matter of sight, the way you see these pictures,” Zhang told NewsChina. “You might follow the procedure carefully and use the best chemicals and papers, but still yield unsatisfactory results.” To Zhang, the question is: “Can your eyes command the image?” Antique Around the year 2000, newspapers gradually embraced digital photography and, one by one, publications’ darkrooms shuttered.

Many of Zhang’s colleagues left the profession.

Only Zhang and his China Youth Daily darkroom miraculously survived. His darkroom is now the only one still in use among China’s major media publications. Master Zuo, with his darkroom, has become an antique in the digital age.

Unable to hold back the torrential wave of digital technology, Zhang, trying to keep up with the times, started to hunt-and-peck at the computer and learned to use Photoshop.

He no longer hand-develops photos for the daily paper. Now Zhang’s main task is to sort out the archive of nearly 100,000 negatives the newspaper has saved since it was established in 1951.

He still treasures his darkroom equipment as much as always, though. “This enlarger has at least 40 years of history!” Zhang said proudly, referring to a transparency projector used to produce photos from negatives.

In the 1970s, the newspaper bought two different enlargers from the US for US$70,000.

The smaller one has been out of work for quite some time, and there is nowhere to fix it. The larger one still works, but its original light bulb is out of stock. Zhang himself spent 1,000 yuan (US$154) to ask a friend to replace it with an LED bulb.

Zhang once feared that digital photos might push the darkroom out of the world of modern photography, but he has found that more and more young people in artistic circles are rediscovering the charm of blackand- white photography, and some are coming to him to learn the craft.

Zhang is quite certain of the advantages of digital photography. He visited famous photographer Zhu Xianmin’s photo exhibition at the National Museum of China earlier

Zhang Zuo’s darkroom in the China Youth Daily offices is the last one still in use by a major Chinese news publication

this year and studied one of the artist’s most famous works, a photo of a toddler looking up at a gnarled old man drinking porridge from a bowl. In the photo, the subtle layers of the man’s thick, cotton-padded jacket were extremely well defined. Zhang knew straight away that this was a digital print. He had once developed it himself in the early ’90s.

“Such an effect could not have been created by human hands,” he told NewsChina. “If a picture is too perfect, it must be the work of a computer. The traditional prints developed by hand in the darkroom always have slight flaws.” But he loves the tradition. When talking about quality black-and-white photographs, Zhang beams with joy. “Look at the black, it’s so glossy!” He said of a photo he loves. “It’s such a pleasure to see such work, I get intoxicated by it!” In Zhang’s view, though black-and-white photos are limited to black, white and gray, they provide infinite space for a viewer’s imagination. When he sees a black-andwhite image, he closes his eyes and envisions his own version of it – the color of a girl’s dress, a beam of sunshine, all of these details come alive in his mind. “It’s beautiful,” he said. But color photos, by contrast, are too realistic to leave enough room for the imagination to roam. After 20 years, the colors in color photos may shift, but “even after 100 years, black-and-white photos will still be black, white and gray,” Zhang added.

He explained how enchanting it is to see a picture develop for the first time; it seems as if an exquisite black-and-silver painting is materializing bit by bit on silky, pearly white paper. Such a rhapsodic experience, earned through hard work and patience, may be completely alien to today’s young photographers who calibrate colors with the click of a mouse.

“If you take a photo with a digital camera, you can see it instantly, but using film creates a feeling of anticipation, Zhang told NewsChina. “You have to wait until you go to the darkroom and develop it [to see how it turned out]. Maybe it will be perfectly exposed, or maybe someone blinked. With this kind of anticipation, you experience a lot of regret, but this is the joy of traditional photography.”

Old Version

Old Version