China’s General Principles of the Civil Law (herein after referred to as the General Principles) published in 1986, which stipulates the basic principles for regulating civil activities, was of immense significance to the then just started process of reform and opening-up. By guaranteeing the equal status of natural and legal persons in personal and property relationships in civil law, the General Principles met the basic requirements for a modern market economy. Its enactment laid the legal basis for China’s transformation from a planned economy to a market-oriented one.

In 1954 and 1962, China tried twice to draft a civil code, but both were dropped due to various reasons, including political turmoil. At that time, the country’s planned economy meant the government controlled the production, distribution and prices of all goods and services. The government owned all enterprises and also planned agricultural production and allocated all social resources. Distribution to individuals was made according to one’s performance at a job, which was assigned. There were almost no private businesses. In this environment, a civil law code, which deals with private matters, lacked the social soil to take root.

In 1978, as reform and opening-up began, China’s legislature decided to establish a civil law system. Primarily based on the Continental Law System (or Civil Law System), the Chinese legal system consists of written laws set down by the legislative body and follows the tradition of codifying core principles and separate regulations of a certain law department into a referable system. But at that time of momentous changes, the legislature found that making a complete civil code, to include both basic principles and separate regulations (or branches) of civil law, was daunting. It eventually took a flexible path–enacting the separate regulations of civil law successively in the first place before the time was mature to consolidate them into a civil code.

This has been regarded a rational and wise decision. In the wake of the enactment of a series of separate regulations, China passed the General Principles in 1986. Based on that, the General Provisions of the Civil Law was passed in 2017, considered the opening chapter of a civil code. Jiang Ping, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law who was a member of the draft team for the General Principles, once said that China’s civil code might have remained blank today if not for this flexible strategy.

What to Govern?

In 1978, late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping pointed out that China should establish its own criminal law, civil law, procedural law and other laws it lacked. He elaborated that the relationships between the country and enterprises as well as enterprises and individuals should also be regulated by law to solve the conflicts between them.

But it was a big challenge to develop a civil law then. The first question was what social relationships civil law should govern. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the country was under a planned economy for several decades. Civil activities were planned or arranged by the government without involving much interaction between natural persons and legal persons or between the two.

In 1979, Peng Zhen, one of the principal founders of China’s modern legal system who led the Commission of Legislative Affairs (CLA), an organization in charge of legal affairs under National People’s Congress Standing Committee, shared his confusion with members of the CLA, admitting that it would be a big project to deal with several layers of social relationships properly without experience from the past.

There were disputes over what relationships it should regulate. Court officials held that civil law should regulate only marriage, the family and property inheritance. But the jurisprudential circle believed the concept of the civil relationship should be rather broad, at least to include contractual relations and intellectual property relations.

In spite of that, members of the CLA were enthusiastic about making a civil code. A team of over 30 experts was soon organized to work on the draft. Meanwhile, Peng suggested that separate regulations on the civil law should be enacted simultaneously to play safe, realizing that it would be too difficult to make a complete civil code all at once.

In 1982, the CLA, led by late Chinese leader Xi Zhongxun, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s father, proposed that separate regulations of a civil law could get passed first if passing a systematic civil code was too challenging, given the urgent demand for regulations. The legal talents of the team were divided about this: some persisted in making a civil code while others held that separate regulations should be released earlier. In the end, the commission decided to pause drafting the civil code. The enactment of separate regulations of the civil law continued. This decision left some law experts confused and disappointed.

At that time, China’s law circles believed the country should make a civil code as soon as possible, because it represented the level of civilization of a society, as Liang Huixing, a jurist who joined drafting the General Principles, recalled in an article.

But 20 years later, Liang saw wisdom in the pause. “If we did make a civil code then, it would have been one that copied from the former Soviet Union and reflected the characteristics and requirements of the planned economy, which was not in a position to provide a legal basis for pushing forward reform and opening-up and developing a socialist market-oriented economy in China,” wrote Liang.

Standardizing the Rules

A series of separate regulations in the civil law code were issued from 1980, including the Economic Contract Law, Trademark Law, Patent Law, Law on Succession and the Law on Economic Contracts Concerning Foreign Interests.

In the process, it grew increasingly urgent to standardize the basic rules that these separate regulations have in common, such as the basic principles for civil activities, the definition of civil subjects, legal person system, civil rights and civil liability.

The problem prompted some legal specialists to propose drafting a civil code again. After re-evaluating the possibility, the legislative body concluded that a fundamental law was in need for the regulation of all kinds of civil relationships, but still, the time was not yet ripe for a civil code.

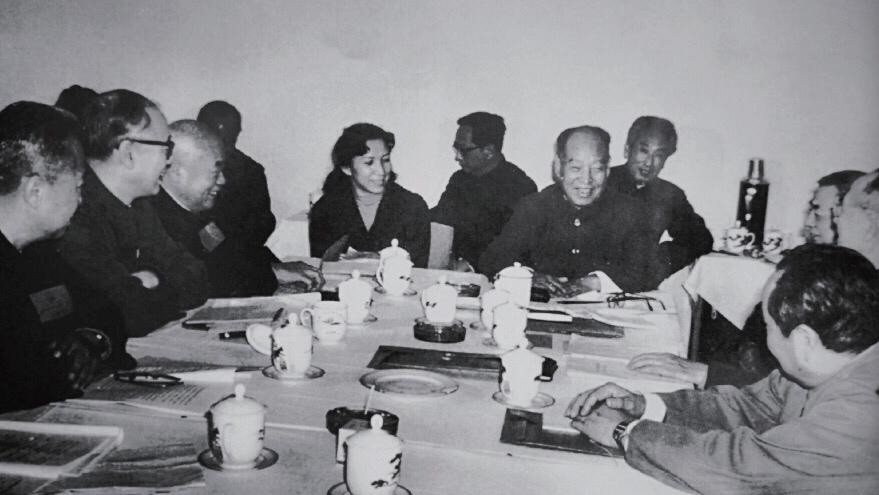

In 1985, the CLA started to draft general principles for a civil law as a substitute. In December that year, the legislative body held a conference in Beijing to discuss the draft of the General Principles. At the conference, legal experts and judicial officials reached consensus, viewing it as a necessary and feasible step to set some general principles for a civil law at that time.

But soon after, a discussion on economic law was held in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, by the Economic Law Research Center of the State Council and the Chinese Society of Economic Law. It turned out to be one against the draft of the General Principles. During the conference, some scholars particularly criticized Article 2 of the draft, which stipulated that China’s civil law aimed to regulate the property and personal relationships between citizens, between legal organizations, and between the two. They argued that this wording made all property relationships subject to civil law and denied the function of economic law, namely the economic laws and regulations that govern the commercial and economic relationships emerging in the country’s macroeconomic management. Some could not accept that the passed separate regulations, such as the Economic Contract Law and Trademark Law, were regarded as part of civil law, insisting that they came under economic law.

Gu Ming, an influential figure in economic law who was then director of the Economic Law Research Center of the State Council, pointed out at the meeting that a socialist commodity economy, which is planned based on public ownership of the means of production, required a new legal department that reflected its characteristics. He regarded economic law as the most suitable one.

This discussion renewed the historical disputes between economic law and civil law in the country that started in 1979 after a national symposium was held in Beijing. Some experts amplified the role of economic law, which, they believed, should regulate social relationships between government organs, enterprises, public institutions and other social organizations and citizens, and civil law only needed to govern property and non-property relationships between citizens.

But other legal scholars believed all horizontal economic relations, including property relationships between social organizations, between social organizations and citizens and between citizens, should be regulated by civil law.

The debate between economic law and civil law, as professor Jiang noted, reflects “the dispute over the direction of China’s economic development – whether to remain planned or market-oriented – and the argument over the role of planning and the role of the market in the reform of the Chinese economy at that time.

Noting the contradictory opinions, Peng Zhen, who was then chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, demanded the legislative body hold a symposium for economic law experts and invited them to speak freely about the draft of the General Principles. They particularly sought out Gu Ming and listened to his opinion.

At that time, China had just started reform and opening-up and society was braced for change and uncertainties. Gu elaborated that a socialist society like China was dominated by public ownership instead of private ownership like in capitalist countries. So there remained fundamental questions to clarify as to how to stipulate ownership in law, which should not get fixed too early with “general principles.” He believed that economic relations between legal persons should be regulated by economic law.

After studying Gu’s suggestion, the legislative body put forward a report which wrote that the economic relations between legal persons – particularly non-State-owned enterprises – that had equal status, such as in economic contracts, were horizontal economic relations and thus feasible to be regulated by civil law. Such provisions, the report added, were made to meet the requirements of reform to the economic system, decrease administrative intervention into economic management and strengthen the law’s ability to manage the economy.

Meanwhile, the report stated that the relationships the civil law were to govern, a main point of controversy in economic law circles, were revised to “property relationships and personal relationships between civil subjects with equal status, that is, between citizens, between legal persons and between citizens and legal persons.”

This provision reflected two basic principles of civil law: First, the subjects of commodity-money relations, which account for the majority of civil relations, have equal legal status and rights; second, civil law mainly regulates property relations between subjects with equal status, and relations that involve unequal subjects, such as the country’s management of the economy and, relations between the State and enterprises, would be regulated by economic law.

After the draft of the General Principles was agreed by the Secretariat of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, the working body of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and its Standing Committee, the disputes over economic law and civil law continued. But Peng persisted, saying that academic debate was not a reason to stop making general principles for civil law. In April 1986, the General Principles eventually were passed.

The enactment of the General Principles is regarded as a great breakthrough in China’s legal history. In the mid-1980s, the planned economy system was about to change, but the goal and direction of the reform on China’s economy was not yet determined.

Basic Principles

In that era of change, the General Principles recognized and guaranteed the civil conduct between subjects with equal status in the form of law and set “equality” as its fundamental nature, establishing basic principles such as equality, voluntariness, fairness, making compensation for equal value, honesty and credibility to guide civil activities, and encouraged market diversification. These principles fit the basic requirements for a modern market economy and provided a legal basis for China’s transformation from a planned to a market economy.

In addition, the spirit of democracy in the lawmaking process is impressive. When legal experts held a meeting in Guangzhou to oppose the draft of the General Principles, the Party and government leadership did not criticize the conference but asked the legislative body to listen to their advice instead. The brainstorm eventually led to the revision of the social relations the civil law should regulate, which is regarded as a more accurate sphere.

More than 30 years have passed. Some defects in the General Principles are obvious against the evolution of civil law today. For example, when mentioning a legal person’s right to dispose of his or her personal property and real property, it used “property ownership and property rights related to property ownership,” which was lengthy, instead of directly using “property rights.” Some regulations are marked with the stamp of the planned economy and do not fit a market economy. But these are shortfalls that can be explained by the limitations of that period.

China’s civil law has progressed since then, most importantly. Revisions have been made to the General Principles and separate regulations of civil law have been perfected. In 2015, China again put enactment of a civil code on the agenda. In 2017, China passed the General Provisions of the Civil Law, which constitutes the basic framework of China’s civil law system and lays the foundation for a complete civil code expected to come out around 2020.

The author is former vice director of the Commission of Legislative Affairs under the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress

Old Version

Old Version