In the years since I became ill, licensed drugs have cost me my home and bled my family dry. Now we have cheaper drugs that save our lives, but you say they are fake and take them away. I don’t want to die. I want to live… Sir, can you tell me which family doesn’t have a patient, and can you guarantee that you’ll have a lifetime free of illness?” These are the words spoken by an elderly leukemia patient to a policeman who confiscates unapproved drugs from patients in the film Dying to Survive.

The scene has struck a chord with audiences for touching on a burning social problem in China – the difficulty and costliness of accessing medical treatment.

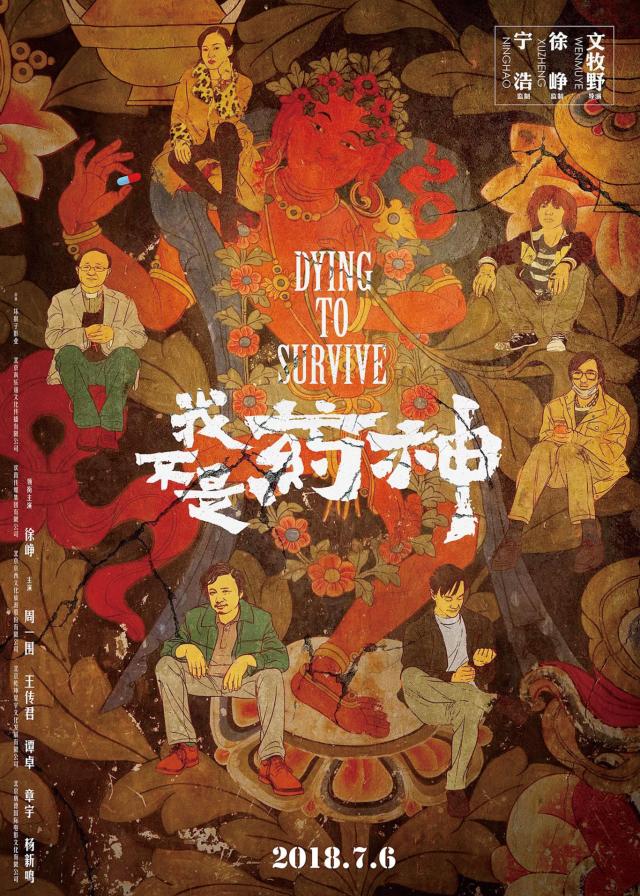

Released on July 5, Dying to Survive quickly became one of the country’s most discussed and highest-grossing movies in years. It has reportedly taken in 2.3 billion yuan (US$34 million) in the first 11 days since its release, and scored a rating of 8.9/10 on Chinese film portal Douban.com based on 533,587 reviews – the highest score for a domestic feature in over a decade.

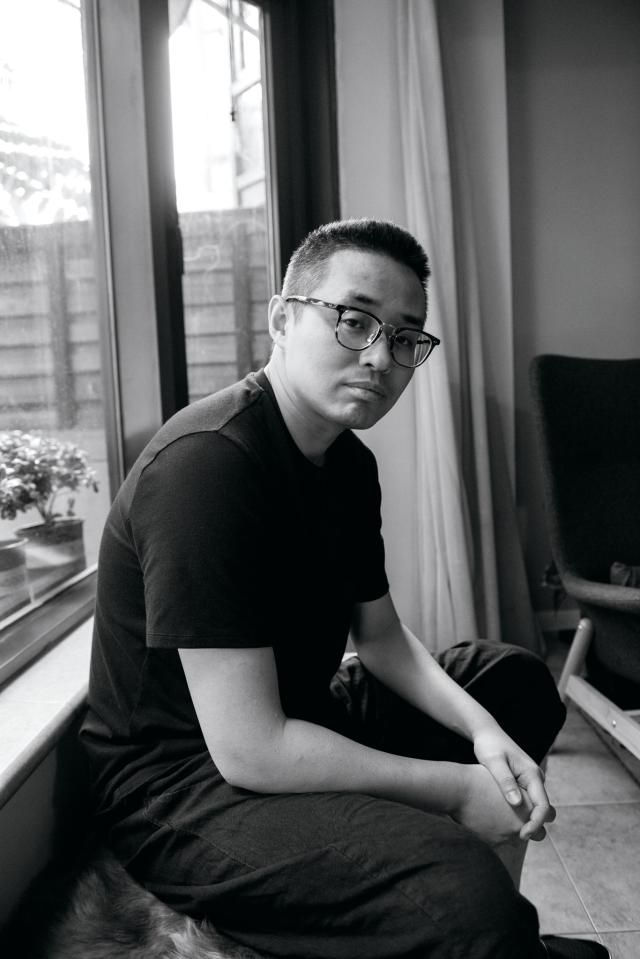

The film was made by 33-year-old director Wen Muye and co-produced by the hit maker Ning Hao, who is known for low-budget black comedies Crazy Stone (2006), Crazy Racer (2009) and Guns and Roses (2013).

Dubbed China’s Dallas Buyers Club by the foreign press, Dying to Survive is based on the true story of a businessman with leukemia who imported cheap generic drugs from India to help himself and his fellow patients. As a social drama that boldly probes deep social problems, the film has been acclaimed as a breakthrough in the Chinese film industry.

In the story, protagonist Cheng Yong, played by established comedy actor Xu Zheng, is a store owner peddling “Indian Magical Oil,” which he claims is an aphrodisiac. But Cheng’s life changes when a leukemia patient approaches him for help procuring the generic version of a Swiss cancer drug from India.

The medication is called Glinic, which appears to be a thinly-veiled reference to Gleevec, a drug developed by Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. At a cost of 40,000 yuan (US$6,000) for a month’s supply of 120 tablets, Glinic is far too expensive for low-income patients to afford. Nevertheless, the cost price of the Indian generic drug can be as low as 500 yuan (US$74).

Smelling the enormous potential profits, Cheng teams up with an unlikely gang of “smugglers” – the patient who asked him for help, a rebellious blond-haired country boy, a pious priest and a single mother who works in a night-bar as an exotic dancer to pay for her daughter’s leukemia treatments.

Cheng smuggles the unapproved drug to China and helps thousands of cancer patients get much cheaper medicine at 5,000 yuan (US$750). He is seen as a hero by those who cannot afford the expensive licensed drug. Noticing the spread of a generic alternative, the Swiss pharmaceutical company turns to the Chinese police to find the smuggler.

Concerned about the risks involved, Cheng abandons the project and establishes a garment factory. But he is later shocked by the suicide of his friend, a leukemia patient who was left penniless after purchasing the expensive branded treatments. Cheng resumes procuring the Indian drug for Chinese patients, and this time, he opts to sell it at the cost price of 500 yuan to save more lives.

Cheng is caught by police and sentenced to jail for five years. The film ends with a touching scene: a large crowd of patients lines up on the street to show their respect and gratitude to Cheng as he is taken away by a prison van.

The movie is based on the true story of Lu Yong, a textile trader who suffered from leukemia. Lu spent US$80,000 on Gleevec, which was not covered by national health insurance at the time. Lu smuggled a generic version from India and helped at least 1,000 other Chinese leukemia sufferers.

Lu was arrested in 2014 and charged with selling fake drugs. More than 300 leukemia patients petitioned for his release, stating that Lu had not personally profited from the sales. Lu’s case captured the Chinese public’s attention and stirred wide debate. Many paralleled his case with Dallas Buyers Club, the 2013 film about a man who sells unregulated pharmaceutical drugs to AIDS sufferers in the 1980s.

After being detained for four months, Lu was acquitted in 2015. When he was writing the script, director Wen Muye had in-depth discussions with Lu Yong and dozens of leukemia patients. One character in the movie was based on the true story of a patient who was diagnosed with leukemia when his wife was five months pregnant. He became suicidal when the family could not afford the expensive drugs. The patient burst into tears at the first glance of his newborn son, who gave him the resolve to live on.

“Each character in the movie can’t be simply categorized as good or bad. Smugglers, patients, authorities, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, they all have their own point of view. You can’t say who is right or who is wrong. So I chose a relatively neutral standpoint – emphasizing human nature – to tell the story. Such a stance also helped the movie dodge the risk of being censored too much,” Wen told NewsChina.

Wen knew when he started writing the script that he wanted to do a genre film, even though the co-producer Ning Hao’s initial intention was to make an art film for a niche market.

The director hopes the movie speaks to more than educated elites in first-tier cities – but can also reach down the market to fourth-and fifth-tier cities and draw people who don’t usually go to the cinema. “Reach down, down, and down further,” Wen said, making a slow, downward gesture.

From Wen’s perspective, enriching the film with comedy was necessary to make it more accessible. He had no intention of remaking Dallas Buyers Club, the style of which, he believed, made it inaccessible to the broader public. Helping everyday people empathize with the protagonist is the crux of his approach.

In the original script, the protagonist was a leukemia patient who procured cheaper Indian drugs to save himself and others. Wen ultimately abandoned this thread.

“Why does he [the protagonist] have to be a patient? Why can’t we choose the perspective of an ordinary man to tell the story?” Wen thought hard about this while revising the script. It was a way to make the story more emotional, multi-layered and convincing as the audience follows his character arc from merely seeking profits to risking prison in order to save lives.

“It’s easier for audiences to get into the community of patients and feel for them through the perspective of a non-patient, especially when the protagonist is an Indian magical ointment peddler from society’s lower rungs,” Wen said, emphasizing that the character development of a flawed everyman has plenty of appeal.

“There is no lack of quality art films targeted at the niche market in Chinese cinema. We have lots of them. What we really need are works that combine entertainment, social criticism and thought-provoking elements. Many Oscar-winning films, such as Schindler’s List and Forrest Gump, are fun, entertaining, bittersweet and full of humanity. This is the kind of movie I wanted to make,” Wen said.

Wen doesn’t regard himself as an intellectual, even though he graduated from the prestigious Beijing Film Academy with a master’s degree and was supervised by Tian Zhuangzhuang, a master filmmaker of China’s “Fifth Generation” along with Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige.

But Wen admits he is a fan of pop culture and enjoys South Korean drama My Love from the Star (2013) and the insanely popular Japanese manga One Piece.

The box office success of Dying to Survive may prove Wen’s strategy successful. The film grossed 163 million yuan (US$24m) in previews before it was even officially released. It later raked in 700 million yuan (US$104m) in just three days after its official release on July 5. The box office tracking app Maoyan estimates the film will reach 3.8 billion yuan (US$568m) in total takings.

“Combining realistic themes with commercial appeal to spark a wider discussion over the issue as well as the film, instead of making an art film for a small group of elites, is the biggest breakthrough of the film,” Wen told our reporter.

At a pre-release screening on July 3, the crew appeared after the end credits began to roll, welcomed by a standing ovation.

“I am a leukemia patient. Thank you so much for creating such a great film,” said a young man in the first row, giving a deep bow to the whole crew to show his gratitude.

“I was touched at that moment, really,” Wen told our reporter, “He [the patient] expressed his feelings in a very controlled way, but you could see the tears in his eyes. I shook hands with him afterward and asked him what drugs he was taking. He told me he has had licensed drugs for 10 years, and the medicine has now been included under medical insurance.”

The Chinese government has taken measures over the past few years to make cancer medication more affordable. Fifteen cancer drugs, including Gleevec, have been covered by health insurance schemes since 2017, meaning public health funds pay up to 80 percent of their cost. In May this year, China exempted import tariffs on cancer drugs and reduced value-added tax on such drugs from 17 percent to three percent. However, with a typical month’s worth of Gleevec pills now costing 23,000 yuan, a subsidized year of treatment will still leave patients more than 55,000 yuan (US$8,200) out of pocket.

On July 8, after the movie sparked a nationwide discussion over drug prices, China’s medical insurance administration announced it would bring down the price of drugs already in its catalog and continue adding to the list of subsidized medicines after negotiating with pharmaceutical companies on pricing.

“Social problems always exist. Every pain, failure and effort deserves to be valued when we strive to make society a better place. I hope my film can bring positive energy to the audience. […] But there is also a sort of fake ‘positivity,’ which requires people to ignore hardship and real-life problems. It’s wrong to babble about positivity and avoid facing reality,” Wen told our reporter.

“If, after experiencing all kinds of hardship and suffering, one still maintains a positive attitude toward life – I think that is real positivity. We can frankly admit that our society has problems, but we’re convinced that one day those problems will be solved and our society will be better. That is the message this movie intends to deliver,” Wen said.

The director admitted with candor that the emotional intensity of the latter part of the film

was no accident – including the deaths of two main characters, Cheng Yong’s arrest, and the final scene where hundreds of patients line up in the streets to show their gratitude.

“It would have been better if I could have managed the emotional part more precisely. In the movie I’ve done 85 or 90 percent of it, but I could have done better,” Wen said.

“Those Hollywood masters, like David Fincher and [Steven] Spielberg, can seize – even quantify – audiences’ emotions to the extreme. They know what jokes make more southerners laugh than northerners do. It’s a capability born of decades of experience.”

“There are many basic skills that Chinese filmmakers need to practice and acquire, and to grasp emotions and feelings so precisely is an essential skill – you should know exactly what makes audiences laugh and what make them cry,” the director said with two sharp snaps of his fingers.

Wen admires the acclaimed Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu, who made the well-received movies The Revenant (2015) and Birdman (2014).

Wen’s next project is another accessible film about a social hero, but with a more international focus. “I’ve just started to write it and hope it can be filmed later next year,” Wen said.

“Popular films based on real life are really needed in Chinese cinema,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version