Qu was born and raised in Beijing. After graduating from the prestigious Peking University with a degree in biology she went on to study art history in New York for six years.

“If I hadn’t returned to China to do film production, I would probably be working at a museum right now, studying ancient art,” the director said, smiling.

She enjoyed the rich artistic environment in New York, where she attended numerous film exhibitions, lectures and salons.

“MoMA has the largest collection of arthouse movies in the world. It regularly holds arthouse and independent film screenings. It was there that I realized how splendid a world films have created,” Qu said.

“But to get a real understanding of movies, one still needs practice,” Qu told our reporter. And that was the main reason for Qu’s return to China in 2003.

Since 2007, Qu has produced a series of independent films, including Night Train (2007), Knitting (2008), Longing for the Rain (2013) and Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014). The latter won the Golden Bear for Best Film, alongside the Silver Bear for Best Actor, at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival in Berlin in 2014.

Qu has gained a reputation within the industry but insists on keep a certain distance from the “show business” world. Her media profile is low-key, and she refuses to attend grand celebrity parties. “They won’t give you anything except a feeling of emptiness,” she said. “Instead, I feel rich and full when I read, watch films, observe and pay attention to ordinary people’s lives and the society we are living in.”

In 2013, Qu made her directorial feature debut, Trap Street, which tells a story of a young digital map-maker who finds his computerized maps have been mysteriously altered – after he becomes infatuated with a young woman who works for China’s intelligence service on a street that does not officially exist.

Qu uses the metaphor of the invisible street to symbolize “those prevalent but implicit secrets of the changing reality of modern China.” She would like the film to be seen as a meditation on modern society instead of a simple love story.

Qu has faced challenges common to arthouse directors, in fundraising, shooting and audience receptions. But most challenging, she says, is gaining the trust of others. Yet she remains optimistic and believes making good quality films is the key.

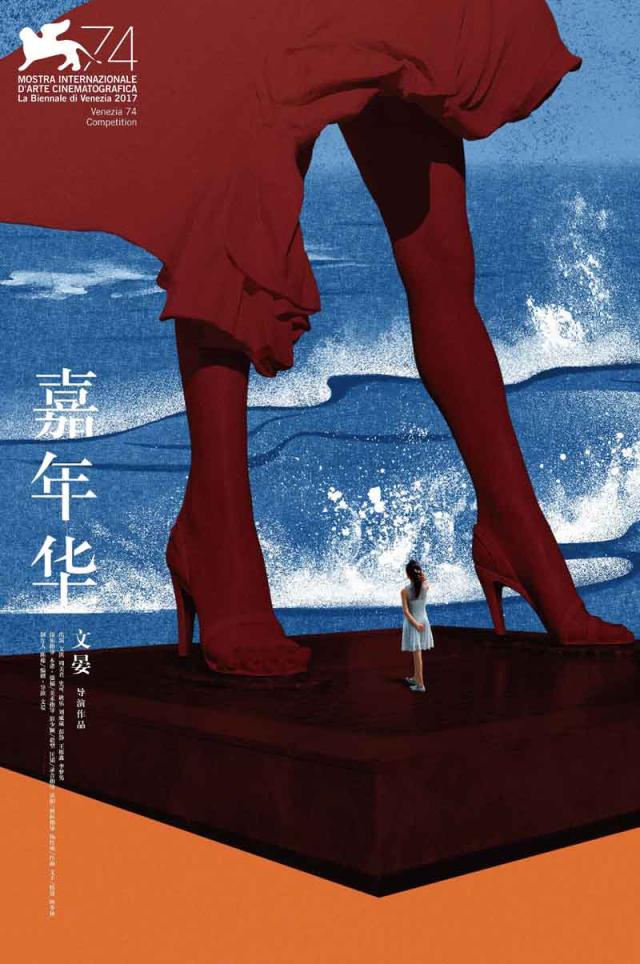

As a vital figure in China’s independent cinema scene, Qu weaves her social observations and concerns into her works. She hopes her new film will generate a discussion on sexual education and child protection in her home country.

“We are trying to tell educators that sexual education is important at an early age, because children need to learn how to protect themselves, and because parents are not always around,” Qu told Reuters in an interview.

Old Version

Old Version