Old Version

Old Version

Robert Carl Cohen

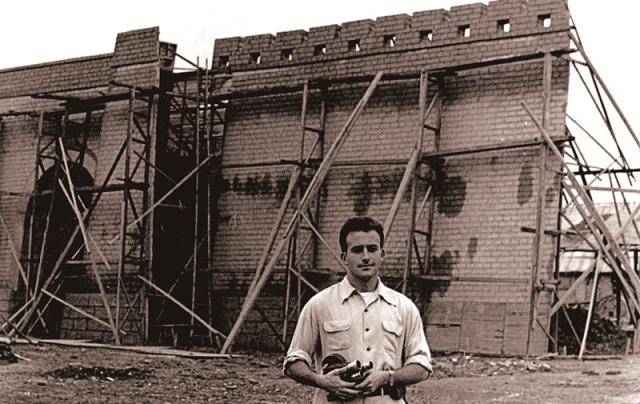

Risking his entire career and even freedom in the US, Robert Carl Cohen, a 27-year-old director from Philadelphia, set out on a six-week forbidden journey to China along with 40 other young Americans in 1957.

Equipped with a 16mm camera and eleven 100-foot rolls of 16mm black and white film, Cohen traveled to eight cities and later made a 50-minute documentary Inside Red China, which included sensitive footage of Chairman Mao Zedong, Premier Zhou Enlai, military jet aircraft, tanks, political prisoners and the October 1st National Day parade. Before that, no Westerner had ever had the chance to document the newly-established PRC on film and delve into the daily lives of the people.

During the period of frozen relations between the US and China, when the Korean War (1950-1953) had not officially ended and the clouds of a potential third world war were gathering, the young man, who tried hard to stick to journalistic objectivity, was willing to take every risk to show his fellow countrymen what China was really like.

“Filming in China, so that the US public could see the truth about conditions there, might – I hoped – contribute in even a very small way to avoiding war,” 60 years later, the 87-year-old Cohen told NewsChina.

In 1957, Cohen was living in Paris as a doctoral student in Social Psychology at the prestigious Sorbonne. While attending the 6th World Youth Festival in Moscow, he and 41 other American youth were invited to China by the All-China Federation of Democratic Youth (ACFDY).

The head of NBC-TV in Moscow, Irvine R. Levine, offered Cohen a contract to take their 16mm camera and film whatever he could.

They went despite a clear warning from the State Department that their passports would be revoked, that they might have difficulty getting passports in the future and that they might “make themselves liable to prosecution for trading with an enemy” on the grounds that the Korean War had not officially ended.

Christian A. Herter, under-secretary of State, said in a special message to each of the travelers that the youth would be “willing tools” of Communist propaganda if they made the trip.

Nevertheless, these 42 Americans, whose ages ranged from 19 to 35, defended the trip by saying they had the “right to travel.”

All the Americans making the journey showed their passports and submitted their passport numbers to get visas issued by the Chinese Embassy. These visas, however, were issued on separate pieces of paper so there would be no official record that any of them had been in China.

The delegation made a nine-day, 9,000-kilometer trip across Siberia from Moscow to Beijing. The original 42-people group was reduced to 41 when one delegate, Shelby Tucker of Mississippi, refused to show his US passport to the PRC Immigration Authorities and was later deported back to Moscow.

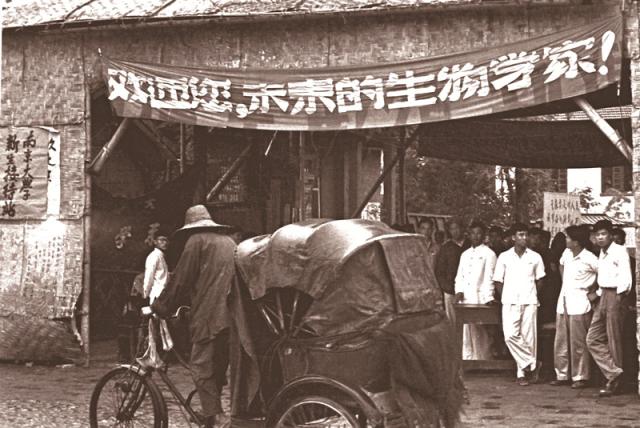

In contrast to the anti-American propaganda common in China at the time, the group of young Americans were warmly greeted by a crowd of 3,000 Chinese students at Peking Railway Station with applause and bouquets.

To welcome the US youth delegation, the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League formed a special group to accompany the travel group, led by Zhu Liang, the then director of International Liaison Department of the Communist Youth League.

Zhu, in his later writing, pointed out that the 1957 trip was highly valued by the central government, especially by Premier Zhou Enlai. Zhou made a principle for the hospitality – “seeking sameness but keeping difference” and ordered that the guests’ requirements be satisfied as much as possible.

As honored guests, the group was accommodated in various first-class hotels in the eight cities they visited. “Since I was from a working-class family with limited financial means, eating such things as a three-course dinner in a first-class hotel was a very unusual and pleasant experience,” Cohen told NewsChina.

Despite having an MA, Cohen had never been required to take a single course about China. He told our reporter that at that time he was also a US Army soldier stationed at NATO Headquarters in Paris and had seen some of the plans for military actions for the assumed World War III.

“Even my limited knowledge (as a high school student I had read the famous 1946 ‘Smyth Report’ on the development of the atomic bomb) had led me to the realization that nuclear war would lead to the destruction of all life on the planet,” Cohen told NewsChina. Thus, for the young director, becoming the first American to film China since its founding in 1949 had a special purpose – he hoped he could use his camera to make a small contribution to global peace.

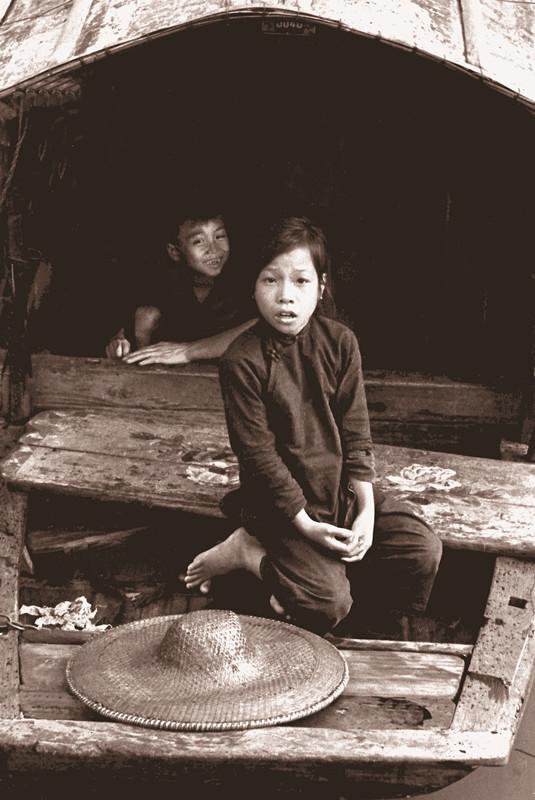

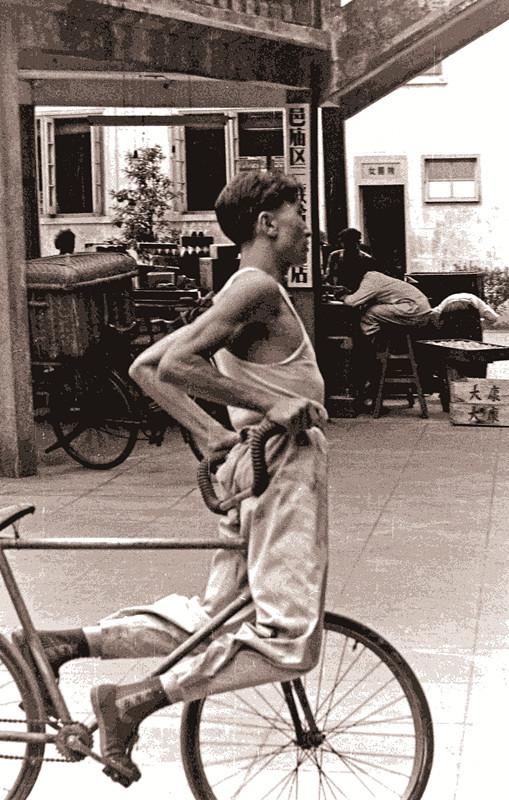

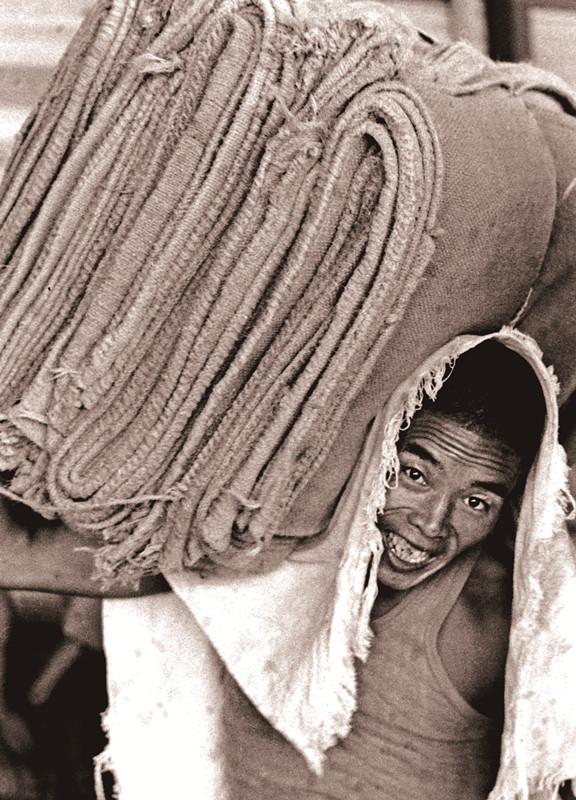

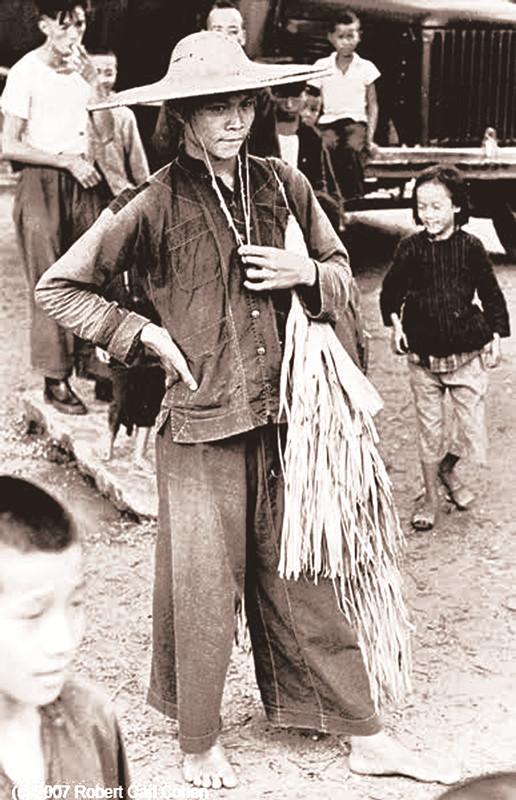

Photos shot by Cohen in his 1957 visit to China: a dashing police officer patrolling the “Shanghai Great World,” an entertainment complex; Tanka children living on boats in Guangzhou; an acrobat at “Shanghai Great World”; student orientation at the Biology Department of Nanking University; a dock worker on the Yangtze River; a commune member in Guangdong Province; a student of Nanking University in her dorm.

During the 56 days, the group were shown a carefully controlled set of various parts of the nation and lives of different classes. Not only were they led to what would later be famous tourist spots such as the Great Wall, the Temple of Heaven, and a Peking opera house, they were also introduced to vital parts of Chinese society, including its schools, hospitals, factories, fields, communes, prisons and even slums.

“Having virtually no knowledge about China beforehand, I was impressed by virtually everything,” Cohen said.

“It is a vast land of great contrasts,” he narrated in Inside Red China.

Modern machinery was employed in hospitals and factories. Cohen and his fellow travelers visited a children’s hospital in Beijing, and saw the relatively new technology of X-rays, 50 years old in the West but new in China. New machines and facilities supplied by the Soviet Union were being operated in factories and ports. At that time, some Western economists, as Cohen pointed out in the documentary, predicted that “within 10 years, China will become the third-biggest industrial power, right after the US and Russia.”

But in reality, as Cohen told NewsChina, China was still technologically undeveloped, with most of the labor performed by pre-modern animal and manpower. Through his lens, he captured the rickshaw coolies on streets of Shanghai as still the primary source of transport. He also filmed workers loaded with bricks on their backs in the process of Great Wall reconstruction, and they were happy to be paid more if they could carry more bricks.

In China, anti-American propaganda, undoubtedly, drew the entire delegation’s attention. In the documentary, Cohen shows several anti-American posters. A typical poster depicts a US military jeep stuck in mud, with a caption saying “American militarists want war, but they are stuck in the mud when all the other nations want peace.”

However, despite the anti-American propaganda, the group was surprised by the hospitality of the Chinese. “What I found most interesting was the friendly attitude of essentially everyone we met towards the US. Other than official anti-US propaganda posters, nobody said or did anything unfriendly towards us,” Cohen said.

As honored guests, Cohen and other delegates were invited to a reception given by the Premier and Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai, who made a very positive impression on Cohen as a moderate, intelligent and pragmatic realist. The young Cohen himself had the chance to ask Zhou a question about China’s foreign policy towards anti-communist former colonial and newly emerging nations.

Zhou answered him, saying that, “China will support all formerly colonial and newly emerging nations regardless of their internal policies.” This answer, from Zhou’s perspective, was significant because it implied the PRC’s readiness to interact with the US and other non-Communist nations.

A surprising degree of freedom was given to the US delegates. They were allowed to meet the 24-year-old American POW Morris Wills, who was captured by China during the Korean War and chose to stay in China at the end of the war. Subsidized by the Red Cross, Wills studied Chinese literature in Peking University and became a star player on the basketball team before returning to the US in 1965. Ten out of the 41 were permitted to visit Shanghai Prison to interview the two imprisoned CIA paramilitary officers John Downey and Richard Fecteau, captured on a mission to Manchuria in 1952 and eventually released in 1973.

In the Shanghai prison, Cohen filmed how political prisoners gathered together to receive daily reeducation sessions, with fellow prisoners reading selections of Marxist publications. They concentrated intently on the teaching, for their imprisonment might be shortened if they could demonstrate their familiarity with and loyalty to Communism.

The group was welcomed to visit the October 1st National Day parade. To Cohen’s surprise, he was able to film the jet planes and tanks and was given special permits by the PRC Foreign Ministry to mail his exposed but undeveloped film from China to NBC in Moscow without a single frame ever being censored or even seen by any Chinese official.

The young director also documented the intimate moments of Chinese people.

When visiting a slum by the Suzhou Creek area in Shanghai, the group was greeted with crowds of wide-eyed children who kept staring at them, laughing and running after their cars.

“It was a friendly greeting,” Cohen recalled. “I was told that most Asians have little body hair, but I, like most Europeans have rather hairy arms. The children wanted to figure out whether I was a monkey.”

In Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong Province, the group visited the Tanka community, which made a deep impression on Cohen. The Tanka people, also known as sampan dwellers, are an ethnic subgroup who traditionally lived on boats in coastal parts of Southern China. In Guangzhou, there were over 100,000 people living on boats on the Zhujiang River, the largest river in Southern China.

“These people were from the lowest class in China,” Cohen described, “They were so poor that they used little sampan boats as their homes.”

Cohen visited one Tanka family and was surprised to find three generations living side by side in the cramped boat. The mother and girls were gathering twigs for the evening fire. They had meat for dinner.

In the past, as Cohen pointed out, it was very unusual for these people to eat any meat at all. The strict rationing system started by the government, “although it limited every one to a small amount,” had enabled the poor sampan dwellers to get meat that they couldn’t afford before.

80 percent of Tanka children attended the free school run by the government. In a small wooden room built on a raft, Tanka children, all wearing floats in case the boat sank, were taught to read and write by the dim light from a naked bulb.

“Without living in China for years, even the most observant reporter cannot experience the daily joys and sorrows that are most important to the average man,” Cohen said.

27-year-old Robert Carl Cohen in China in 1957

After the visit, the delegates ran into their share of trouble.

Upon landing in New York, Cohen refused to surrender his passport to the US Customs officials. He later read in the New York Times that, other than him, all of the others in the delegation had their passports confiscated, some even in Hong Kong where the British Immigration officials had handed them to US Immigration officials.

Although Cohen sent the footage he took to NBC, he found that NBC’s policy had been to only broadcast scenes of Americans who were defying the “travel ban.” Everything else, especially the footage of Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai, was not shown to the US public.

“It was evident to me that NBC had made a policy decision to only partially defy the US State Department’s effort to prevent the US public from learning about China,” Cohen said.

He then made the untelevised footage into the 50-minute documentary film Inside Red China. He began showing it first at private gatherings and then at universities throughout the USA and Canada. He was contracted to give lectures at over 100 schools and civic groups, earning up to $1,000 per lecture – a fortune at the time. “Good money in the 1960s, when you could buy a new Volkswagen for as little as $1,200,” Cohen said jokingly.

Cohen told our reporter that, despite a few threatening letters and an occasional telephone threat, the general reaction was positive, as American people were extremely interested in seeing inside the secretive nation.

In the early 1960s, he added music and narration and converted the footage into a television show which was syndicated worldwide as part of The Special of the Week series. Following J. F. Kennedy’s 1960 Presidential victory, Cohen received a letter of commendation for Inside Red China from the Office of Under-Secretary of State, Chester Bowles.

In 1978, Cohen was invited again to return to China by the ACFDY, during which trip he discovered that despite the improvements made since 1957, the internal conflicts of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution had slowed, and in many cases, destroyed many of the gains achieved since 1949.

In 2015, the 85-year-old director once again returned to China to retrace the route he took in 1957. For Changchun TV, he filmed over 300 hours of video in 12 cities, Inside Robert Carl Cohen’s China. The greatest impression of his latest trip was that China had been able to both survive and overcome the internal problems which had formerly prevented development. He noted that the Reform and Opening Up process have greatly improved the average quality of life.

For Cohen, the courageous visit to China in 1957 changed his life and gave him a completely new and different perspective. “I now saw it as not merely another nation, but as a quarter of the population of the planet, as a vast sea of humanity striving to raise itself out of poverty and civil strife,” Cohen told NewsChina.