Acclaim for writer Shao Yanxiang’s work has been growing in recent years thanks to his critical essays targeting the unfairness of society and bad practices among members of the current ruling Communist Party of China (CPC). It has earned him the moniker the “modern Lu Xun,” after the short story writer and essayist well known for his sharp criticism in the 1920s and 30s that lashed out against the darkness of society under Kuomintang (KMT) rule.

However, it was just this political criticism that saw Shao labeled a “rightist” in the late 1950s as the CPC launched a sweeping class struggle aimed at cleaning out the supposed bourgeoisie and “counterrevolutionaries” who they believed were attempting to “uglify” socialism and even to seize power from the Party, according to Shao’s book.

Shao was banished to remote farms to do hard labor and was deprived of the right to publish for almost 20 years until he was rehabilitated in 1979, three years after the end of China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The miserable period, from the late 50s to late 70s, according to Shao, enabled him to cool down and take a look back at the road both he and the country had walked.

“I did not recount and re-determine my footprints until my later years. I am reexamining myself when I am reconsidering history. Or, in other words, I am reexamining history when I am reconsidering myself,” he wrote in the preface of his latest autobiographical book I Died, I Survive, I Testify.

‘Died’ in 1958

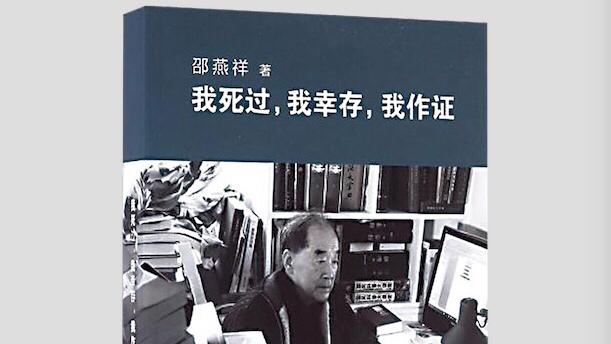

Despite the simplicity of the typesetting, Shao’s new book garnered a great deal of attention with its long and slightly odd title page dedication through which, according to the Writers Publishing House, the book’s publisher, Shao is citing the writer Franz Kafka: “Anyone who cannot cope with life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate… but with his other hand he can jot down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different and more things than the others; after all, he is dead in his own lifetime and the real survivor.”

Shao found it a good title and added “I testify” to the end, saying that life would become meaningless if someone did nothing but only survived.

For Shao, his “death” came in 1958 when he was forced to sign a confession and accept the label of “rightist.” The accusation was based on two of his articles written in 1957. One was a commentary which supported criticism against bureaucratism – when governance is heavily influenced by bureaucracy – among some CPC officials, and the other was a poem criticized by Yao Wenyuan, then a government official in charge of literature and later a member of the “Gang of Four” in the Cultural Revolution, for containing the unhealthy thoughts of “feudal officials” such as looking down upon the working people.

It was a shock for Shao, who had admired and followed the CPC since he was a boy. He joined the Party in 1953 and had worked for the State-run China National Radio since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, where he got through a lot of ink extolling Chairman Mao Zedong and China’s socialist construction.

“I had been a member of ‘us’ [the CPC], but suddenly I was kicked out,” he says in I Died, I Survive, I Testify, commenting on his expulsion from the Party, believing that it was the end of his political career, equivalent to a “death.”

Self-analysis

“I fell from flappy ‘romance’ to prostrate ‘realism.’ I turned from a ‘man of character’ to a man ‘who vowed to be obedient’,” Shao wrote in the preface to his 2004 book In Search of the Soul – Shao Yanxiang’s Personal File: 1945-1976.

After being politically rehabilitated, Shao never stopped examining himself and wrote several autobiographical works, in which he often blamed himself for being too naïve to have a clear picture of the political situation or to have sensed the potential risks.

At that time, Shao believed that criticism would help the ruling Party discover the problems hidden in its work, especially in its lower levels, and so would further benefit socialist development. “Expanding democracy and fighting bureaucratism will help create a clean and new social atmosphere which lets the people ‘be people in a healthier and more reasonable way.’ This is what Lu Xun expected for the new society when he was in the dark,” Shao proclaims in the new book.

“While we were singing songs [in praise of] the bright side, we should also take a critical look at the other sides, which were concentrated on bureaucratism. I think [the criticism of bureaucratism] complied with the political propaganda of the [then] top leaders,” he argues.

Faithful to such ideas, Shao wrote several critical essays and poems in the 1950s, ignoring an implied warning from one of his teachers. “[The teacher] asked me not to write satirical poetry and instead go back to lyric ones… But it was too late by the time I came to understand the depth of meaning behind his words,” he recalls.

Like many young people at the time, Shao first started to embrace the Communist Party Ideas when Japan began to invade northeastern China in the 1930s involving the enslavement of Chinese people at a time when corruption within the ruling KMT was rampant and it violently suppressed supporters of democracy, leading to widespread disillusionment.

A new, independent country became Shao’s dream, especially after he read Mao Zedong’s 1945 report On Coalition Government (also known as The Fight for a New China), in which Mao proposed to “put an end to the KMT’s dictatorship and set up a new coalition country” which was dependent on enhancing the inner-Party development and better serving and unifying the masses.

Shao worked hard to follow his dream. Thanks to the strong democratic atmosphere at Shao’s junior middle school, founded by an American Christian church, Shao, along with several others students, even launched a one-sheet newspaper they would paste on the wall, criticizing and satirizing the KMT’s scandal-riddled dark side. In 1947, Shao joined the Federation of Democratic Youth, which was recorded by Shao as his “coming-of-age ceremony.”

It was a long and carefree time for Shao, so happy was he that he now finds it uncomfortable to recall today. “When some bad CPC members set me up in the Cultural Revolution 20 years later, I told myself that if the Party members I had met and worked with in my youth had been like those guys, I would have kept far away from the CPC, never mind follow them,” he wrote. In his new book, he partly attributes his “naïvety” towards the political situation to his “blind belief in and worship of” Mao Zedong.

Re-examining History

Nevertheless, in Shao’s eyes, Mao Zedong and the CPC had the strategic vision and wisdom to found a new country and serve the Chinese people. That was why he had no qualms with working for State media and producing propaganda about “socialist construction” with all his heart.

The “blind belief” he described in his book was that “he had seldom asked why or doubted any policy of the Party or the government” even when he sensed something amiss or wrong.

For example, when Shao joined in the “land reform” the CPC launched in 1947 in the liberated areas which aimed to redistribute rural land held by landlords, he realized that the campaign might have strayed too far to the left, as the Party neither distinguished ordinary landlords from the more unscrupulous and oppressive ones, nor gave the ordinary landlords any alternative options for making a living, which actually created resistance to the reform. But at that time, he believed that the Party was always right.

Shao also feels a certain remorse for not questioning the 1956 relocation of the Sanmenxia power station in Henan Province, for which hundreds of thousands of local residents were forced to move to remote and sterile saline and alkaline land. According to Shao, the Chinese side of the project unquestioningly followed the Soviet experts’ erroneous analysis of Sanmenxia’s geology which then caused the sediment of the Yellow River to block the reservoir. However, as a government propagandist at the time, he did not speak for the residents and opponents, but rather sang praise for the project based on his “unrealistic and romantic fantasy.”

“In the piles of documents available to the public, the government always concludes the achievements, but seldom reflects on the mistakes and detours they made… so it is hard for them to learn a lesson,” wrote Shao when he reexamined land reform in his book.

His words might indicate a reason why many intellectuals at the time, including Shao, became concerned about the dark sides of society and the defects in Party officialdom, especially when the government encouraged people to “fully air their views” on the Party in the late 1950s.

“I thought that we could not expand the bright side until we fought and eliminated the dark sides. It is a dialectic of ‘serving the politics’ which is deeper and more direct,” says Shao in I Died to explain his shift to critical essays.

Despite the intellectuals’ expectation when providing criticism, much of what they wrote was subsequently deemed to be “ignoring the achievements of socialist construction and trying to uglify it.”

In his new book, Shao repeatedly mentions the well-known “‘Counter-Revolutionary’ Case of Hu Feng,” in which Hu, a renowned literary critic of the time, was arrested for publicly blaming officials for ignoring the laggard and dark sides in the socialist construction, and appealing for writers and critics to launch independent, non-governmental journals. Shao, however, was originally only a spectator to the incident, failing to realize that he would one day fall as a “rightist” due to his critical essays.

Today, the political campaigns of the late 1950s still remain a sensitive topic in China, though discussion of them is not banned, Shao frankly points out in I Died that political campaigns would always spread to and affect large groups of innocent people and violate the “rule of law.”

In his later years, Shao has kept a close eye on China’s development and reform, especially of the legal system, Party disciplinary supervision and elections, which he believes have plenty of room to improve when he examines history.

“After ‘we have crossed the river by feeling for the stones’ [Deng Xiaoping’s description of how to conduct China’s process of reform and modernization], it is a challenge, not a fantastical dream for us to take a new, correct and sunny road … To learn the lessons from our bloody history and rationally say ‘yes’ or ‘no’,” he wrote at the end of the preface to his new book.

Encouragingly, I Died, though sharp and bold, was published without issue or censorship and drew the attention of young Chinese people. “There is little time left for our generation …” he told NewsChina, revealing that he will keep reading and writing to leave his “last words” to the world and the younger generations.

Old Version

Old Version