A critical issue for space exploration is the load capacity of the launching vehicle. Since the first Long March-1 launch vehicle lifted off in 1970, a total of 17 different types of launch vehicles have been produced. To date, China’s total for launch attempts stands at 237 with a success rate of 95 percent.

“China’s Long March rocket series boasts diversified [load] capacities to meet the different demands of civilian as well as foreign clients,” explained Long Lehao, a rocket expert at the China Academy of Engineering, “Furthermore, the series performs far more reliable.” Rocket technology has undergone significant development in recent years, particularly with the introduction of the Long March 5/6/7 series that have phased out previous lines.

The Long March-5 Space Launch Vehicle (CZ-5) builds the heavy-lift component that will ultimately replace the country’s current Long March rocket series. Operated alongside the Long March 5 rockets are the medium-lift Long March-7 and smaller CZ-6 rockets, together covering the entire spectrum of launch types, ranging from cargo to crew, for missions to China’s planned space station. On November 3, China successfully conducted the maiden launch of CZ-5 at the Wenchang Space Launch Centre in Hainan Province.

“Long March 5 rockets perform equally to the European Ariane 5, the American Delta IV and Atlas V, which all belong to the top level rocket series across the globe,” Long Lehao told NewsChina.

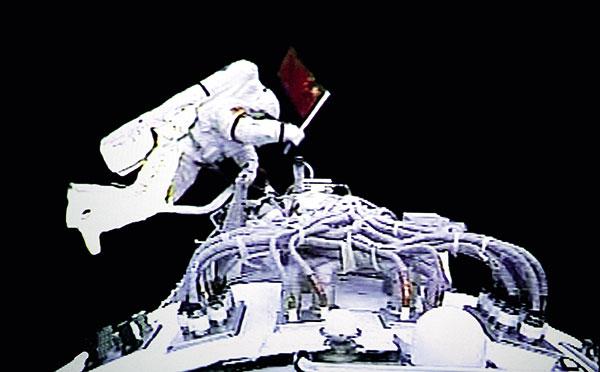

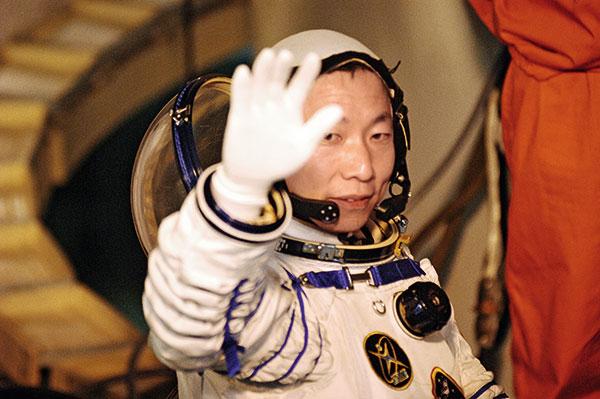

Development of rocket technology is aimed at allowing the development of manned space engineering attempts. October 17, a Long March 2F launcher successfully lifted the Shenzhou-11 spacecraft into orbit. On board the spacecraft were two astronauts who will stay aboard the Tiangong-2 module for 30 days, returning in mid November, to carry out a number of medical and space science experiments.

The mission is part of a mid-stage effort to develop a permanent space station. Yang Liwei, former Chinese astronaut and now vice director of the China Manned Space Engineering Office, has indicated publicly that the station is expected to be completed by 2020. According to Yang, China’s space station has reserved portals for future cooperation with other countries, and designed connection portals to be compatible with other modules. “In the development of the space station project, China is willing to be open to international cooperation and communication on project design, equipment manufacturing, space utilization, astronaut training, and arranging a joint flight program,” said Yang in a previous interview with the official Xinhua news agency.

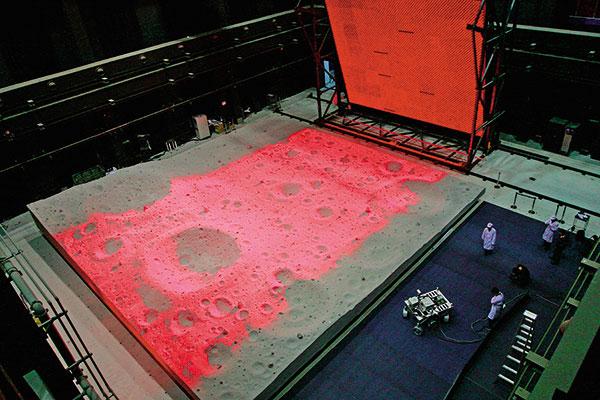

The next step for the Long March series is to develop a heavy-lift rocket. The planned dimensions of the rocket would be a 10 meter diameter, and 100 meter length. It will carry over five times the cargo of the largest rocket currently in use, surpassing the US’ next generation rocket, NASA’s Space Launch System. It will be able to handle manned moon exploration, a round-trip sampling mission to Mars and many other space exploration missions across the solar system. According to Tang Yihua, deputy president of China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, China’s heavy-lift rocket is expected to be ready for launch between 2027 and 2030.

Commercial Application

Increasing the load capacity of the launch vehicles is intended to capitalize on international commercial demand. According to statistics provided by rocket expert Long Lehao, by the end of 2015, there were a total of 42 international commercial launch assignments for the Long March series, which saw 42 satellites and 12 carriers taken into designated orbits. Long Lehao told NewsChina that the share of China-made rockets on the international market is still not significant, for reasons including unfair market competition.

He went on to explain that due to restrictions by the US, any countries that have used American components in their launch vehicles are not allowed to use China-made rockets. According to Tang Yihua, China turned to a cooperation with the European Space Agency to get away from US monopoly. “For example, China and France jointly produced the ITAR-free satellite [International Traffic in Arms Regulations is the US regulation that classes all space hardware as weaponry] without using any US-made components, thus allowing the launch of the satellite by the Long March series.”

Other factors such as the increasing number of private enterprises in this market have squeezed the meager market share that China had previously enjoyed. SpaceX, a US private enterprise entered the market with the unprecedented low cost of a single commercial launch at less than US$62 million. Now Europe, the US and Japan are conducting research into developing low-cost rockets, aiming to cut the price of a single rocket launch to less than half of the current price. “Taking all these elements into consideration, the Long March series is facing ever more severe market pressure,” said Tang.

Aerospace Industry

The first Long March 7 rocket was successfully launched on June 25, 2016 at Wenchang on China’s Hainan Island, marking the official operation of China’s fourth launchpad after Jiuquan, Xichang and Taiyuan Space Launch Centers.

Locating the new space center in Wenchang can lower transportation cost due to its lower latitude and favorable ground-shipping conditions. Operations at the new center can also benefit China within the international commercial launch market. “It is estimated that over 100 satellites are to be launched from Wenchang between 2016 and 2025,” He Zhibin, an aerospace expert from the International Academy of Astronautics told NewsChina.

The Hainan provincial government is more ambitious than just building a single space launch center, and aims to develop Wenchang into an aerospace city that can enjoy a booming economy based on the aerospace industry. “Prospective industries derived from space technology such as aerospace tourism, space agriculture and so on, are proving popular in some countries have not yet been developed domestically,” continued He Zhibin, who visited the Kennedy Space Center and Huntsville Space and Rocket Center in the US and noticed the international trend of expanding the space industry. “The Wenchang center is sure to propel local economic and social development.”

The outcomes of the aerospace opportunity are already being felt in Wenchang. According to Wang Xiaoqiao, Mayor of Wenchang, on the day of the Long March 7 launch alone, the city drew 150,000 tourists. He added, confidently, in September at a public event: “The new launch center will attract more tourists from across the world in the coming years.”

Old Version

Old Version